Related Research Articles

Sulfur (also spelled sulphur in British English) is a chemical element with the symbol S and atomic number 16. It is abundant, multivalent and nonmetallic. Under normal conditions, sulfur atoms form cyclic octatomic molecules with a chemical formula S8. Elemental sulfur is a bright yellow, crystalline solid at room temperature.

The green sulfur bacteria are a phylum, Chlorobiota, of obligately anaerobic photoautotrophic bacteria that metabolize sulfur.

Seagrasses are the only flowering plants which grow in marine environments. There are about 60 species of fully marine seagrasses which belong to four families, all in the order Alismatales. Seagrasses evolved from terrestrial plants which recolonised the ocean 70 to 100 million years ago.

A cold seep is an area of the ocean floor where hydrogen sulfide, methane and other hydrocarbon-rich fluid seepage occurs, often in the form of a brine pool. Cold does not mean that the temperature of the seepage is lower than that of the surrounding sea water. On the contrary, its temperature is often slightly higher. The "cold" is relative to the very warm conditions of a hydrothermal vent. Cold seeps constitute a biome supporting several endemic species.

The purple sulfur bacteria (PSB) are part of a group of Pseudomonadota capable of photosynthesis, collectively referred to as purple bacteria. They are anaerobic or microaerophilic, and are often found in stratified water environments including hot springs, stagnant water bodies, as well as microbial mats in intertidal zones. Unlike plants, algae, and cyanobacteria, purple sulfur bacteria do not use water as their reducing agent, and therefore do not produce oxygen. Instead, they can use sulfur in the form of sulfide, or thiosulfate (as well, some species can use H2, Fe2+, or NO2−) as the electron donor in their photosynthetic pathways. The sulfur is oxidized to produce granules of elemental sulfur. This, in turn, may be oxidized to form sulfuric acid.

Sulfate-reducing microorganisms (SRM) or sulfate-reducing prokaryotes (SRP) are a group composed of sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB) and sulfate-reducing archaea (SRA), both of which can perform anaerobic respiration utilizing sulfate (SO2−

4) as terminal electron acceptor, reducing it to hydrogen sulfide (H2S). Therefore, these sulfidogenic microorganisms "breathe" sulfate rather than molecular oxygen (O2), which is the terminal electron acceptor reduced to water (H2O) in aerobic respiration.

The sulfur cycle is a biogeochemical cycle in which the sulfur moves between rocks, waterways and living systems. It is important in geology as it affects many minerals and in life because sulfur is an essential element (CHNOPS), being a constituent of many proteins and cofactors, and sulfur compounds can be used as oxidants or reductants in microbial respiration. The global sulfur cycle involves the transformations of sulfur species through different oxidation states, which play an important role in both geological and biological processes. Steps of the sulfur cycle are:

Sulfur-reducing bacteria are microorganisms able to reduce elemental sulfur (S0) to hydrogen sulfide (H2S). These microbes use inorganic sulfur compounds as electron acceptors to sustain several activities such as respiration, conserving energy and growth, in absence of oxygen. The final product of these processes, sulfide, has a considerable influence on the chemistry of the environment and, in addition, is used as electron donor for a large variety of microbial metabolisms. Several types of bacteria and many non-methanogenic archaea can reduce sulfur. Microbial sulfur reduction was already shown in early studies, which highlighted the first proof of S0 reduction in a vibrioid bacterium from mud, with sulfur as electron acceptor and H

2 as electron donor. The first pure cultured species of sulfur-reducing bacteria, Desulfuromonas acetoxidans, was discovered in 1976 and described by Pfennig Norbert and Biebel Hanno as an anaerobic sulfur-reducing and acetate-oxidizing bacterium, not able to reduce sulfate. Only few taxa are true sulfur-reducing bacteria, using sulfur reduction as the only or main catabolic reaction. Normally, they couple this reaction with the oxidation of acetate, succinate or other organic compounds. In general, sulfate-reducing bacteria are able to use both sulfate and elemental sulfur as electron acceptors. Thanks to its abundancy and thermodynamic stability, sulfate is the most studied electron acceptor for anaerobic respiration that involves sulfur compounds. Elemental sulfur, however, is very abundant and important, especially in deep-sea hydrothermal vents, hot springs and other extreme environments, making its isolation more difficult. Some bacteria – such as Proteus, Campylobacter, Pseudomonas and Salmonella – have the ability to reduce sulfur, but can also use oxygen and other terminal electron acceptors.

A seagrass meadow or seagrass bed is an underwater ecosystem formed by seagrasses. Seagrasses are marine (saltwater) plants found in shallow coastal waters and in the brackish waters of estuaries. Seagrasses are flowering plants with stems and long green, grass-like leaves. They produce seeds and pollen and have roots and rhizomes which anchor them in seafloor sand.

Beggiatoa is a genus of Gammaproteobacteria belonging to the order Thiotrichales, in the Pseudomonadota phylum. This genus was one of the first bacteria discovered by Ukrainian botanist Sergei Winogradsky. During his research in Anton de Bary's laboratory of botany in 1887, he found that Beggiatoa oxidized hydrogen sulfide (H2S) as an energy source, forming intracellular sulfur droplets, with oxygen as the terminal electron acceptor and CO2 used as a carbon source. Winogradsky named it in honor of the Italian doctor and botanist Francesco Secondo Beggiato (1806 - 1883), from Venice. Winogradsky referred to this form of metabolism as "inorgoxidation" (oxidation of inorganic compounds), today called chemolithotrophy. These organisms live in sulfur-rich environments such as soil, both marine and freshwater, in the deep sea hydrothermal vents and in polluted marine environments. The finding represented the first discovery of lithotrophy. Two species of Beggiatoa have been formally described: the type species Beggiatoa alba and Beggiatoa leptomitoformis, the latter of which was only published in 2017. This colorless and filamentous bacterium, sometimes in association with other sulfur bacteria (for example the genus Thiothrix), can be arranged in biofilm visible to the naked eye formed by a very long white filamentous mat, the white color is due to the stored sulfur. Species of Beggiatoa have cells up to 200 µm in diameter and they are one of the largest prokaryotes on Earth.

Anoxic waters are areas of sea water, fresh water, or groundwater that are depleted of dissolved oxygen. The US Geological Survey defines anoxic groundwater as those with dissolved oxygen concentration of less than 0.5 milligrams per litre. Anoxic waters can be contrasted with hypoxic waters, which are low in dissolved oxygen. This condition is generally found in areas that have restricted water exchange.

Gammaproteobacteria is a class of bacteria in the phylum Pseudomonadota. It contains about 250 genera, which makes it the most genus-rich taxon of the Prokaryotes. Several medically, ecologically, and scientifically important groups of bacteria belong to this class. It is composed by all Gram-negative microbes and is the most phylogenetically and physiologically diverse class of Proteobacteria.

Lucinidae, common name hatchet shells, is a family of saltwater clams, marine bivalve molluscs.

Solemya velum, the Atlantic awning clam, is a species of marine bivalve mollusc in the family Solemyidae, the awning clams. This species is found along the eastern coast of North America, from Nova Scotia to Florida and inhabits subtidal sediments with high organic matter (OM) content and low Oxygen, such as salt ponds, salt marshes, and sewage outfalls.

Codakia orbicularis, or the tiger lucine, is a species of bivalve mollusc in the family Lucinidae. It can be found along the Atlantic coast of North America, ranging from Florida to the West Indies.

Ctena orbiculata, commonly known as the dwarf tiger lucine, is a species of bivalve mollusc in the family Lucinidae. It can be found along the Atlantic coast of North America, ranging from North Carolina to the West Indies.

Isorenieratene /ˌaɪsoʊrəˈnɪərətiːn/ is a carotenoid light harvesting pigment produced exclusively by the genus Chlorobium. Chlorobium are the brown-colored strains of the family of green sulfur bacteria (Chlorobiaceae). Green sulfur bacteria are anaerobic photoautotrophic organisms meaning they perform photosynthesis in the absence of oxygen using hydrogen sulfide in the following reaction:

Euxinia or euxinic conditions occur when water is both anoxic and sulfidic. This means that there is no oxygen (O2) and a raised level of free hydrogen sulfide (H2S). Euxinic bodies of water are frequently strongly stratified, have an oxic, highly productive, thin surface layer, and have anoxic, sulfidic bottom water. The word euxinia is derived from the Greek name for the Black Sea (Εὔξεινος Πόντος (Euxeinos Pontos)) which translates to "hospitable sea". Euxinic deep water is a key component of the Canfield ocean, a model of oceans during the Proterozoic period (known as the Boring Billion) proposed by Donald Canfield, an American geologist, in 1998. There is still debate within the scientific community on both the duration and frequency of euxinic conditions in the ancient oceans. Euxinia is relatively rare in modern bodies of water, but does still happen in places like the Black Sea and certain fjords.

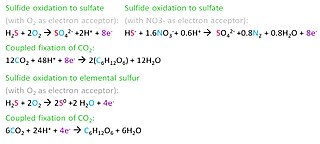

Microbial oxidation of sulfur is the oxidation of sulfur by microorganisms to build their structural components. The oxidation of inorganic compounds is the strategy primarily used by chemolithotrophic microorganisms to obtain energy to survive, grow and reproduce. Some inorganic forms of reduced sulfur, mainly sulfide (H2S/HS−) and elemental sulfur (S0), can be oxidized by chemolithotrophic sulfur-oxidizing prokaryotes, usually coupled to the reduction of oxygen (O2) or nitrate (NO3−). Anaerobic sulfur oxidizers include photolithoautotrophs that obtain their energy from sunlight, hydrogen from sulfide, and carbon from carbon dioxide (CO2).

The hydrothermal vent microbial community includes all unicellular organisms that live and reproduce in a chemically distinct area around hydrothermal vents. These include organisms in the microbial mat, free floating cells, or bacteria in an endosymbiotic relationship with animals. Chemolithoautotrophic bacteria derive nutrients and energy from the geological activity at Hydrothermal vents to fix carbon into organic forms. Viruses are also a part of the hydrothermal vent microbial community and their influence on the microbial ecology in these ecosystems is a burgeoning field of research.

References

- ↑ Núria Marbà; et al. (2007), "Iron Additions Reduce Sulfide Intrusion and Reverse Seagrass (Posidonia oceanica) Decline in Carbonate Sediments", Ecosystems, 10 (5): 745–756, doi:10.1007/s10021-007-9053-8, hdl: 10261/88858 , S2CID 24303572

- ↑ Marianne Holmer; et al. (2009), "Sulfide intrusion in the tropical seagrasses Thalassia testudinum and Syringodium filiforme", Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 85 (2): 319–326, doi:10.1016/j.ecss.2009.08.015

- ↑ Harald Hasler-Sheetal and Marianne Holmer (2015), "Sulfide Intrusion and Detoxification in the Seagrass Zostera marina", PLOS ONE, 10 (6): e0129136, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129136 , PMC 4452231 , PMID 26030258

- ↑ L.K. Reynolds, P. Berg, and J.C. Zieman (2007), "Lucinid clam influence on the biogeochemistry of the seagrass Thalassia testudinum sediments", Estuaries and Coasts, 30 (3): 482–490, doi:10.1007/bf02819394, S2CID 14461273

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Tjisse van der Heide; et al. (2012), "A Three-Stage Symbiosis Forms the Foundation of Seagrass Ecosystems", Science, 336 (6087): 1432–1434, doi:10.1126/science.1219973, hdl: 11370/23625acb-7ec0-4480-98d7-fad737d7d4fe , PMID 22700927, S2CID 27806510