Thomism is the philosophical and theological school which arose as a legacy of the work and thought of Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274), the Dominican philosopher, theologian, and Doctor of the Church.

The Pontifical University of Saint Thomas Aquinas (PUST), also known as the Angelicum in honor of its patron the Doctor Angelicus Thomas Aquinas, is a pontifical university located in the historic center of Rome, Italy. The Angelicum is administered by the Dominican Order and is the order's central locus of Thomist theology and philosophy.

The Summa Theologiae or Summa Theologica, often referred to simply as the Summa, is the best-known work of Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274), a scholastic theologian and Doctor of the Church. It is a compendium of all of the main theological teachings of the Catholic Church, intended to be an instructional guide for theology students, including seminarians and the literate laity. Presenting the reasoning for almost all points of Christian theology in the West, topics of the Summa follow the following cycle: God; Creation, Man; Man's purpose; Christ; the Sacraments; and back to God.

Reginald of Piperno was an Italian Dominican, theologian and companion of Thomas Aquinas.

Contra errores Graecorum, ad Urbanum IV Pontificem Maximum is a short treatise written in 1263 by Roman Catholic theologian Saint Thomas Aquinas as a contribution to Pope Urban's efforts at reunion with the Eastern Church. Aquinas wrote the treatise in 1263 while he was papal theologian and conventual lector in the Dominican studium at Orvieto after his first regency as professor of theology at the University of Paris which ended in 1259 and before he took up his duties in 1265 reforming the Dominican studium at Santa Sabina, the forerunner of the Pontifical University of Saint Thomas Aquinas, Angelicum, in Rome.

Thomistic sacramental theology is St. Thomas Aquinas's theology of the sacraments of the Catholic Church. It can be found through his writings in the 13th-century works Summa contra Gentiles and in the Summa Theologiæ.

The Pontifical Academy of Saint Thomas Aquinas is a pontifical academy established on 15 October 1879 by Pope Leo XIII. The academy is one of the pontifical academies housed along with the academies of science at Casina Pio IV in Vatican City, Rome.

Francesco Silvestri, O.P. was an Italian Dominican theologian. He wrote a notable commentary on Thomas of Aquinas's Summa contra gentiles, and served as Master General of his order from 1525 until his death.

Serafino Porrecta was an Italian Dominican theologian.

Thomas Aquinas was an Italian Dominican friar and priest, an influential philosopher and theologian, and a jurist in the tradition of scholasticism. He was from the county of Aquino in the Kingdom of Sicily.

Actus essendi is a Latin expression coined by Saint Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274). Translated as "act of being", the actus essendi is a fundamental metaphysical principle discovered by Aquinas when he was systematizing the Christian Neoplatonic interpretation of Aristotle. The metaphysical principle of actus essendi relates to the revelation of God as He Who Is, and to how we as humans perceive God’s essence. Aquinas elaborates on the fact that God’s essence is not perceived as sense data; rather, the essence of God can only be understood partially in terms of the limited participations in God’s actus essendi, that is, in terms of what is real, in terms of God’s effects in the real world.

Angelo Pirotta, O.P. was a Maltese philosopher and educator. In philosophy, his areas of specialization were epistemology and metaphysics.

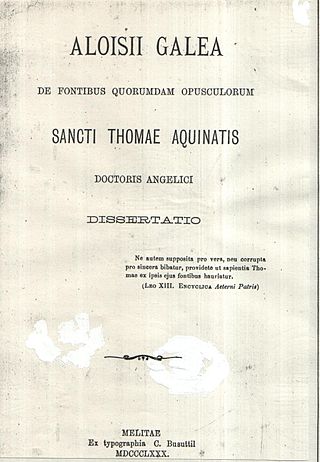

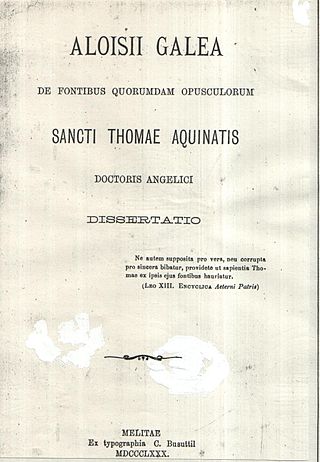

Aloisio Galea (1851–1905) was a Maltese theologian and minor philosopher. He specialised mostly in moral philosophy.

Juan Tomás de Boxadors (1703–1780) was the Master of the Order of Preachers from 1756 to 1777 and a cardinal from 1775 to 1780.

The Editio Leonina or Leonine Edition is the edition of the works of Saint Thomas Aquinas originally sponsored by Pope Leo XIII in 1879.

This is a list of philosophy-related events in the 13th century.

Giuseppe Ciantes, O.P. (1602–1670) was a Roman Catholic prelate, hebraist and theologian who served as Bishop of Marsico Nuovo (1640–1656).

The Triumph of St Thomas Aquinas is a painting by the Italian medieval artist Lippo Memmi, dating likely to 1323, when the former Dominican friar was canonized. It is displayed in the church of Santa Caterina in Pisa, a church once belonging to the Dominican order.

The Quaestiones Disputatae de Veritate by Thomas Aquinas is a collection of questions that are discussed in the disputation style of medieval scholasticism. It covers a variety of topics centering on the true, the good and man's search for them, but the questions range widely from the definition of truth to divine providence, conscience, the good and free decision.