In physics, physical chemistry and engineering, fluid dynamics is a subdiscipline of fluid mechanics that describes the flow of fluids—liquids and gases. It has several subdisciplines, including aerodynamics and hydrodynamics. Fluid dynamics has a wide range of applications, including calculating forces and moments on aircraft, determining the mass flow rate of petroleum through pipelines, predicting weather patterns, understanding nebulae in interstellar space and modelling fission weapon detonation.

Mach number is a dimensionless quantity in fluid dynamics representing the ratio of flow velocity past a boundary to the local speed of sound. It is named after the Austrian physicist and philosopher Ernst Mach.

In physics, a shock wave, or shock, is a type of propagating disturbance that moves faster than the local speed of sound in the medium. Like an ordinary wave, a shock wave carries energy and can propagate through a medium but is characterized by an abrupt, nearly discontinuous, change in pressure, temperature, and density of the medium.

In fluid dynamics, gravity waves are waves generated in a fluid medium or at the interface between two media when the force of gravity or buoyancy tries to restore equilibrium. An example of such an interface is that between the atmosphere and the ocean, which gives rise to wind waves.

Compressible flow is the branch of fluid mechanics that deals with flows having significant changes in fluid density. While all flows are compressible, flows are usually treated as being incompressible when the Mach number is smaller than 0.3. The study of compressible flow is relevant to high-speed aircraft, jet engines, rocket motors, high-speed entry into a planetary atmosphere, gas pipelines, commercial applications such as abrasive blasting, and many other fields.

A hydraulic jump is a phenomenon in the science of hydraulics which is frequently observed in open channel flow such as rivers and spillways. When liquid at high velocity discharges into a zone of lower velocity, a rather abrupt rise occurs in the liquid surface. The rapidly flowing liquid is abruptly slowed and increases in height, converting some of the flow's initial kinetic energy into an increase in potential energy, with some energy irreversibly lost through turbulence to heat. In an open channel flow, this manifests as the fast flow rapidly slowing and piling up on top of itself similar to how a shockwave forms.

In continuum mechanics, the Froude number is a dimensionless number defined as the ratio of the flow inertia to the external field. The Froude number is based on the speed–length ratio which he defined as:

In fluid dynamics, drag is a force acting opposite to the relative motion of any object moving with respect to a surrounding fluid. This can exist between two fluid layers or between a fluid and a solid surface.

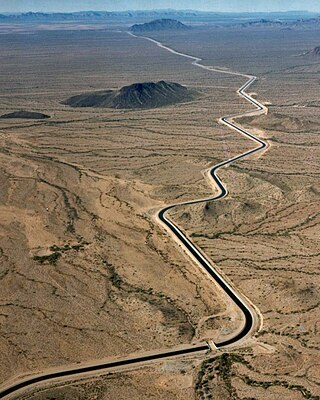

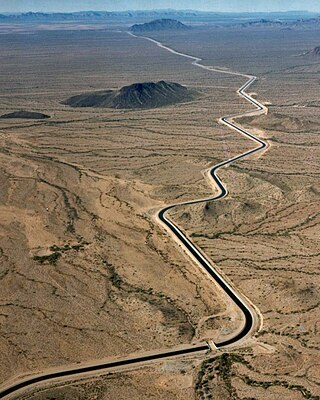

The Manning formula or Manning's equation is an empirical formula estimating the average velocity of a liquid flowing in a conduit that does not completely enclose the liquid, i.e., open channel flow. However, this equation is also used for calculation of flow variables in case of flow in partially full conduits, as they also possess a free surface like that of open channel flow. All flow in so-called open channels is driven by gravity.

In fluid mechanics and hydraulics, open-channel flow is a type of liquid flow within a conduit with a free surface, known as a channel. The other type of flow within a conduit is pipe flow. These two types of flow are similar in many ways but differ in one important respect: open-channel flow has a free surface, whereas pipe flow does not.

The supercritical water reactor (SCWR) is a concept Generation IV reactor, designed as a light water reactor (LWR) that operates at supercritical pressure. The term critical in this context refers to the critical point of water, and must not be confused with the concept of criticality of the nuclear reactor.

Choked flow is a compressible flow effect. The parameter that becomes "choked" or "limited" is the fluid velocity.

Sediment transport is the movement of solid particles (sediment), typically due to a combination of gravity acting on the sediment, and/or the movement of the fluid in which the sediment is entrained. Sediment transport occurs in natural systems where the particles are clastic rocks, mud, or clay; the fluid is air, water, or ice; and the force of gravity acts to move the particles along the sloping surface on which they are resting. Sediment transport due to fluid motion occurs in rivers, oceans, lakes, seas, and other bodies of water due to currents and tides. Transport is also caused by glaciers as they flow, and on terrestrial surfaces under the influence of wind. Sediment transport due only to gravity can occur on sloping surfaces in general, including hillslopes, scarps, cliffs, and the continental shelf—continental slope boundary.

The shallow-water equations (SWE) are a set of hyperbolic partial differential equations that describe the flow below a pressure surface in a fluid. The shallow-water equations in unidirectional form are also called Saint-Venant equations, after Adhémar Jean Claude Barré de Saint-Venant.

The Chézy formula is an semi-empirical resistance equation which estimates mean flow velocity in open channel conduits. The relationship was realized and developed in 1768 by French physicist and engineer Antoine de Chézy (1718–1798) while designing Paris's water canal system. Chézy discovered a similarity parameter that could be used for estimating flow characteristics in one channel based on the measurements of another. The Chézy formula relates the flow of water through an open channel with the channel's dimensions and slope. The Chézy equation is a pioneering formula in the field of fluid mechanics and was expanded and modified by Irish Engineer Robert Manning in 1889. Manning's modifications to the Chézy formula allowed the entire similarity parameter to be calculated by channel characteristics rather than by experimental measurements. Today, the Chézy and Manning equations continue to accurately estimate open channel fluid flow and are standard formulas in all fields that relate to fluid mechanics and hydraulics, including physics, mechanical engineering and civil engineering.

In hydrology stream competency, also known as stream competence, is a measure of the maximum size of particles a stream can transport. The particles are made up of grain sizes ranging from large to small and include boulders, rocks, pebbles, sand, silt, and clay. These particles make up the bed load of the stream. Stream competence was originally simplified by the “sixth-power-law,” which states the mass of a particle that can be moved is proportional to the velocity of the river raised to the sixth power. This refers to the stream bed velocity which is difficult to measure or estimate due to the many factors that cause slight variances in stream velocities.

Hydraulic jump in a rectangular channel, also known as classical jump, is a natural phenomenon that occurs whenever flow changes from supercritical to subcritical flow. In this transition, the water surface rises abruptly, surface rollers are formed, intense mixing occurs, air is entrained, and often a large amount of energy is dissipated. Numeric models created using the standard step method or HEC-RAS are used to track supercritical and subcritical flows to determine where in a specific reach a hydraulic jump will form.

The standard step method (STM) is a computational technique utilized to estimate one-dimensional surface water profiles in open channels with gradually varied flow under steady state conditions. It uses a combination of the energy, momentum, and continuity equations to determine water depth with a given a friction slope , channel slope , channel geometry, and also a given flow rate. In practice, this technique is widely used through the computer program HEC-RAS, developed by the US Army Corps of Engineers Hydrologic Engineering Center (HEC).

Open channel spillways are dam spillways that utilize the principles of open-channel flow to convey impounded water in order to prevent dam failure. They can function as principal spillways, emergency spillways, or both. They can be located on the dam itself or on a natural grade in the vicinity of the dam.

Tides in marginal seas are tides affected by their location in semi-enclosed areas along the margins of continents and differ from tides in the open oceans. Tides are water level variations caused by the gravitational interaction between the moon, the sun and the earth. The resulting tidal force is a secondary effect of gravity: it is the difference between the actual gravitational force and the centrifugal force. While the centrifugal force is constant across the earth, the gravitational force is dependent on the distance between the two bodies and is therefore not constant across the earth. The tidal force is thus the difference between these two forces on each location on the earth.

The Hydraulics of Open Channel Flow: An Introduction. Physical Modelling of Hydraulics Chanson, Hubert (1999)