Administrative law is the division of law that governs the activities of executive branch agencies of government. Administrative law concerns executive branch rule making, adjudication, or the enforcement of laws. Administrative law is considered a branch of public law.

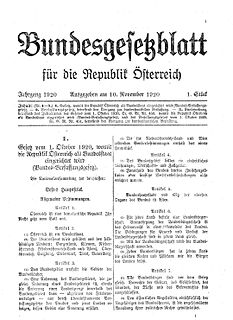

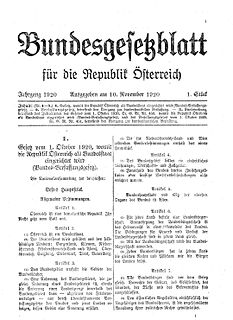

The Constitution of Austria is the body of all constitutional law of the Republic of Austria on the federal level. It is split up over many different acts. Its centerpiece is the Federal Constitutional Law (Bundes-Verfassungsgesetz) (B-VG), which includes the most important federal constitutional provisions.

The Alaska Court System is the unified, centrally administered, and totally state-funded judicial system for the state of Alaska. The Alaska District Courts are the primary misdemeanor trial courts, the Alaska Superior Courts are the primary felony trial courts, and the Alaska Supreme Court and the Alaska Court of Appeals are the primary appellate courts. The chief justice of the Alaska Supreme Court is the administrative head of the Alaska Court System.

The Judiciary of Russia interprets and applies the law of Russia. It is defined under the Constitution and law with a hierarchical structure with the Constitutional Court and Supreme Court at the apex. The district courts are the primary criminal trial courts, and the regional courts are the primary appellate courts. The judiciary is governed by the All-Russian Congress of Judges and its Council of Judges, and its management is aided by the Judicial Department of the Supreme Court, the Judicial Qualification Collegia, the Ministry of Justice, and the various courts' chairpersons. And although there are many officers of the court, including jurors, the Prosecutor General remains the most powerful component of the Russian judicial system.

The judicial system of Turkey is defined by Articles 138 to 160 of the Constitution of Turkey.

The judicial system of Israel consists of secular courts and religious courts. The law courts constitute a separate and independent unit of Israel's Ministry of Justice. The system is headed by the President of the Supreme Court and the Minister of Justice.

The judiciary of Norway is hierarchical with the Supreme Court at the apex. The conciliation boards only hear certain types of civil cases. The district courts are deemed to be the first instance of the Courts of Justice. Jury (high) courts are the second instance, and the Supreme Court is the third instance.

A supreme court is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts in many legal jurisdictions. Other descriptions for such courts include court of last resort, apex court, and highcourt of appeal. Broadly speaking, the decisions of a supreme court are not subject to further review by any other court. Supreme courts typically function primarily as appellate courts, hearing appeals from decisions of lower trial courts, or from intermediate-level appellate courts.

The Judiciary of Austria is the branch of the Austrian government responsible for resolving disputes between residents or between residents and the government, holding criminals accountable, making sure that the legislative and executive branches remain faithful to the European and Austrian constitutions and to international human rights standards, and generally upholding the rule of law. The judiciary is independent of the other two branches of government and is committed to guaranteeing fair trials and equality before the law. It has broad and effective powers of judicial review.

The Judiciary of New York is the judicial branch of the Government of New York, comprising all the courts of the State of New York

The Judiciary of Indonesia constitutionally comprises of the Supreme Court of Indonesia, the Constitutional Court of Indonesia, and the lesser court system under the Supreme Court. These lesser courts are categorically subdivided into the public courts, religious courts, state administrative courts, and military courts.

The Constitutional Court in Austria is the tribunal responsible for reviewing the constitutionality of statutes, the legality of ordinances and other secondary legislation, and the constitutionality of decisions of certain other courts. The Constitutional Court also decides over demarcation conflicts between courts, between courts and the administration, and between the national government and the regional governments. It hears election complaints, holds elected officials and political appointees accountable for their conduct in office, and adjudicates on liability claims against Austria and its bureaucracy.

The Judiciary of Illinois is the unified court system of Illinois responsible for applying the Constitution and law of Illinois. It consists of the Supreme Court, Appellate Court, and circuit courts. The Supreme Court oversees the administration of the court system.

The Supreme Court of Justice is the final appellate court of Austria for civil and criminal cases. Along with the Supreme Administrative Court and the Constitutional Court, it is one of Austria's three courts of last resort.

The judiciary of Michigan is defined under the Michigan Constitution, law, and regulations as part of the Government of Michigan. The court system consists of the Michigan Supreme Court, the Michigan Court of Appeals as the intermediate appellate court, the circuit courts and district courts as the two primary trial courts, and several administrative courts and specialized courts. The Supreme Court administers all the courts. The Michigan Supreme Court consists of seven members who are elected on non-partisan ballots for staggered eight-year terms, while state appellate court judges are elected to terms of six years and vacancies are filled by an appointment by the governor, and circuit court and district court judges are elected to terms of six years.

The Judiciary of the Netherlands is the system of courts which interprets and applies the law in the Netherlands.

The European and Austrian constitutions endow the Austrian court system with broad powers of judicial review. All Austrian courts are charged with verifying that the statutes and ordinances they are about to apply conform to European Union law, and to refuse to apply them if not. A specialized Constitutional Court checks statutes for compliance with the Austrian constitution and executive ordinances for compliance with Austrian law in general.

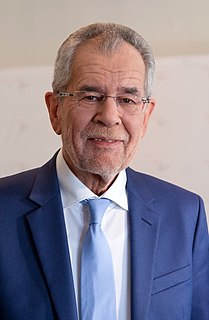

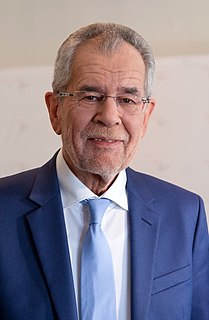

Theodor "Theo" Öhlinger is an Austrian constitutional scholar and educator. Öhlinger was a member the Austrian Constitutional Court from 1977 to 1989 and a professor of constitutional and administrative law at the University of Vienna from 1974 to 2007. Since 1999, he has been serving as the deputy chairman of the board of trustees of the Vienna Museum of Art History. Öhlinger has published 23 books and more than 350 scholarly articles and appears as a frequent commentator on legal issues in the Austrian news media. Austrian President Alexander van der Bellen called him Austria's "operating system" during the turbulent times of May 2019.

In Austrian constitutional law, a minister is a member of the national cabinet. Most ministers are responsible for a specific area of Austrian public administration and stand at the head of a specific department of the Austrian bureaucracy; ministers without portfolio exist and used to be common in the First Austrian Republic but are rare today. Most ministers control a ministry; some ministers control a section of the Chancellery, the ministry headed by the chancellor. A minister is the supreme executive organ within his or her area of responsibility: ministers do not take orders from either the president or the chancellor; their decisions are subject to judicial review but cannot be overruled by any other part of the executive branch.

In Austrian constitutional law, a supreme executive organ , is an elected official, political appointee, or collegiate body with ultimate responsibility for a certain class of administrative decisions – either decisions in some specific area of public administration or decisions of some specific type. The president, for example, is the supreme executive organ with regards to appointing judges; the minister of justice is the supreme executive organ with regards to running the prosecution service; the president of the Constitutional Court is the supreme executive organ with regards to the operational management of the Constitutional Court. The Constitutional Court itself, on the other hand, is not a supreme organ because its decisions, while definitive, are judicial and not administrative in nature.