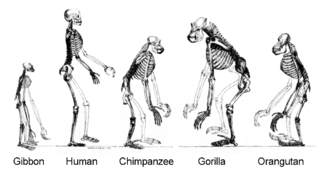

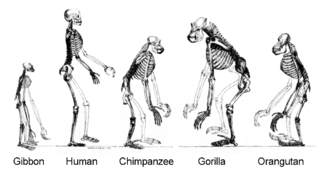

Human evolution is the evolutionary process within the history of primates that led to the emergence of Homo sapiens as a distinct species of the hominid family that includes all the great apes. This process involved the gradual development of traits such as human bipedalism, dexterity, and complex language, as well as interbreeding with other hominins, indicating that human evolution was not linear but weblike. The study of the origins of humans, variously known by the terms anthropogeny, anthropogenesis, or anthropogony, involves several scientific disciplines, including physical and evolutionary anthropology, paleontology, and genetics.

The bonobo, also historically called the pygmy chimpanzee, is an endangered great ape and one of the two species making up the genus Pan. While bonobos are, today, recognized as a distinct species in their own right, they were initially thought to be a subspecies of Pan troglodytes, due to the physical similarities between the two species. Taxonomically, members of the chimpanzee/bonobo subtribe Panina—composed entirely by the genus Pan—are collectively termed panins.

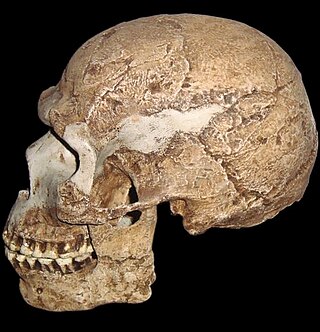

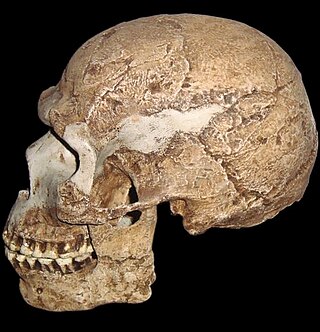

Early modern human (EMH), or anatomically modern human (AMH), are terms used to distinguish Homo sapiens that are anatomically consistent with the range of phenotypes seen in contemporary humans, from extinct archaic human species. This distinction is useful especially for times and regions where anatomically modern and archaic humans co-existed, for example, in Paleolithic Europe. Among the oldest known remains of Homo sapiens are those found at the Omo-Kibish I archaeological site in south-western Ethiopia, dating to about 233,000 to 196,000 years ago, the Florisbad site in South Africa, dating to about 259,000 years ago, and the Jebel Irhoud site in Morocco, dated about 315,000 years ago.

Domestication is a multi-generational mutualistic relationship in which an animal species, such as humans or leafcutter ants, takes over control and care of another species, such as sheep or fungi, so as to obtain from them a steady supply of resources, such as meat, milk, or labor. The process is gradual and geographically diffuse, based on trial and error.

Dog intelligence or dog cognition is the process in dogs of acquiring information and conceptual skills, and storing them in memory, retrieving, combining and comparing them, and using them in new situations.

The domesticated silver fox is a form of the silver fox that has been to some extent domesticated under laboratory conditions. The silver fox is a melanistic form of the wild red fox. Domesticated silver foxes are the result of an experiment designed to demonstrate the power of selective breeding to transform species, as described by Charles Darwin in On the Origin of Species. The experiment at the Institute of Cytology and Genetics in Novosibirsk, Russia explored whether selection for behaviour rather than morphology may have been the process that had produced dogs from wolves, by recording the changes in foxes when in each generation only the most tame foxes were allowed to breed. Many of the descendant foxes became both tamer and more dog-like in morphology, including displaying mottled- or spotted-coloured fur.

The domestication of vertebrates is the mutual relationship between vertebrate animals including birds and mammals, and the humans who have influence on their care and reproduction.

The evolution of human intelligence is closely tied to the evolution of the human brain and to the origin of language. The timeline of human evolution spans approximately seven million years, from the separation of the genus Pan until the emergence of behavioral modernity by 50,000 years ago. The first three million years of this timeline concern Sahelanthropus, the following two million concern Australopithecus and the final two million span the history of the genus Homo in the Paleolithic era.

Richard Walter Wrangham is an English anthropologist and primatologist; he is Professor of Biological Anthropology at Harvard University. His research and writing have involved ape behavior, human evolution, violence, and cooking.

The evolutionary psychology of religion is the study of religious belief using evolutionary psychology principles. It is one approach to the psychology of religion. As with all other organs and organ functions, the brain's functional structure is argued to have a genetic basis, and is therefore subject to the effects of natural selection and evolution. Evolutionary psychologists seek to understand cognitive processes, religion in this case, by understanding the survival and reproductive functions they might serve.

Self-domestication is a scientific hypothesis that suggests that, similar to domesticated animals, there has been a process of artificial selection among members of the human species conducted by humans themselves. In this way, during the process of hominization, a preference for individuals with collaborative and social behaviors would have been shown to optimize the benefit of the entire group: docility, language, and emotional intelligence would have been enhanced during this process of artificial selection. The hypothesis is raised that this is what differentiated Homo sapiens from Homo neanderthalensis and Homo erectus.

Sexual selection in humans concerns the concept of sexual selection, introduced by Charles Darwin as an element of his theory of natural selection, as it affects humans. Sexual selection is a biological way one sex chooses a mate for the best reproductive success. Most compete with others of the same sex for the best mate to contribute their genome for future generations. This has shaped human evolution for many years, but reasons why humans choose their mates are not fully understood. Sexual selection is quite different in non-human animals than humans as they feel more of the evolutionary pressures to reproduce and can easily reject a mate. The role of sexual selection in human evolution has not been firmly established although neoteny has been cited as being caused by human sexual selection. It has been suggested that sexual selection played a part in the evolution of the anatomically modern human brain, i.e. the structures responsible for social intelligence underwent positive selection as a sexual ornamentation to be used in courtship rather than for survival itself, and that it has developed in ways outlined by Ronald Fisher in the Fisherian runaway model. Fisher also stated that the development of sexual selection was "more favourable" in humans.

The Hominidae, whose members are known as the great apes or hominids, are a taxonomic family of primates that includes eight extant species in four genera: Pongo ; Gorilla ; Pan ; and Homo, of which only modern humans remain.

Muscular evolution in humans is an overview of the muscular adaptations made by humans from their early ancestors to the modern man. Humans are believed to be predisposed to develop muscle density as early humans depended on muscle structures to hunt and survive. Modern man's need for muscle is not as dire, but muscle development is still just as rapid if not faster due to new muscle building techniques and knowledge of the human body.

The evolution of schizophrenia refers to the theory of natural selection working in favor of selecting traits that are characteristic of the disorder. Positive symptoms are features that are not present in healthy individuals but appear as a result of the disease process. These include visual and/or auditory hallucinations, delusions, paranoia, and major thought disorders. Negative symptoms refer to features that are normally present but are reduced or absent as a result of the disease process, including social withdrawal, apathy, anhedonia, alogia, and behavioral perseveration. Cognitive symptoms of schizophrenia involve disturbances in executive functions, working memory impairment, and inability to sustain attention.

Neoteny is the retention of juvenile traits well into adulthood. In humans, this trend is greatly amplified, especially when compared to non-human primates. Neotenic features of the head include the globular skull; thinness of skull bones; the reduction of the brow ridge; the large brain; the flattened and broadened face; the hairless face; hair on the head; larger eyes; ear shape; small nose; small teeth; and the small maxilla and mandible.

Domestication syndrome refers to two sets of phenotypic traits that are common to either domesticated plants or domesticated animals.

Brian Hare is a professor of evolutionary anthropology at Duke University. He researches the evolution of cognition by studying both humans, our close relatives the primates, and species whose cognition converged with our own. He founded and co-directs the Duke Canine Cognition Center.

Wild ancestors are the original species from which domesticated plants and animals are derived. Examples include dogs which are derived from wolves and flax which is derived from Linum bienne. In most cases the wild ancestor species still exists, but some domesticated species, such as camels, have no surviving wild relatives. In many cases there is considerable debate in the scientific community about the identity of the wild ancestor or ancestors, as the process of domestication involves natural selection, artificial selection, and hybridization.

Sociodicy is the explanation and exploration of the fundamental goodness of human society. It seeks to provide an account for humans' general success in living together despite their propensity to selfishness, violence, and evil and despite the variation and difference seen across human populations.