Dmitri Dmitriyevich Shostakovich was a Soviet-era Russian composer and pianist who became internationally known after the premiere of his First Symphony in 1926 and thereafter was regarded as a major composer.

The Symphony No. 1 in E minor, Op. 39, is a four-movement work for orchestra written from 1898 to 1899 by the Finnish composer Jean Sibelius.

The Symphony No. 3 in E-flat major, Op. 20 by Dmitri Shostakovich was first performed by the Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra and Academy Capella Choir under Aleksandr Gauk on 21 January 1930.

The Symphony No. 5 in D minor, Op. 47, by Dmitri Shostakovich is a work for orchestra composed between April and July 1937. Its first performance was on November 21, 1937, in Leningrad by the Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra under Yevgeny Mravinsky. The premiere was a "triumphal success" that appealed to both the public and official critics, receiving an ovation that lasted well over half an hour.

The Symphony No. 6 in B minor, Op. 54 by Dmitri Shostakovich was written in 1939, and first performed in Leningrad on November 5, 1939 by the Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra under Yevgeny Mravinsky.

The Symphony No. 8 in C minor, Op. 65, by Dmitri Shostakovich was written in the summer of 1943, and first performed on 4 November of that year by the USSR Symphony Orchestra under Yevgeny Mravinsky, to whom the work is dedicated. It briefly was nicknamed the "Stalingrad Symphony" following the first performance outside the Soviet Union in 1944.

The Symphony No. 11 in G minor, Op. 103, by Dmitri Shostakovich was written in 1957 and premiered by the USSR Symphony Orchestra under Natan Rakhlin on 30 October 1957. The subtitle of the symphony refers to the events of the Russian Revolution of 1905, which the symphony depicts. The first performance given outside the Soviet Union took place in London's Royal Festival Hall on 22 January 1958 when Sir Malcolm Sargent conducted the BBC Symphony Orchestra. The United States premiere was performed by Leopold Stokowski conducting the Houston Symphony on 7 April 1958. The symphony was conceived as a popular piece and proved an instant success in the Soviet Union, his greatest one since the Leningrad Symphony fifteen years earlier. The work's popular success, as well as its earning him a Lenin Prize in April 1958, marked the composer's formal rehabilitation from the Zhdanov Doctrine of 1948.

Symphony No. 12 in D minor, Op. 112, subtitled The Year 1917, was composed by Dmitri Shostakovich in 1961. He dedicated it to the memory of Vladimir Lenin. Although the performance on October 1, 1961, by the Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Yevgeny Mravinsky was billed as the official premiere, the actual first performance took place two hours earlier that same day in Kuybyshev by the Kuybyshev State Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Abram Stasevich.

The Cello Concerto No. 1 in E-flat major, Op. 107, was composed in 1959 by Dmitri Shostakovich. Shostakovich wrote the work for his friend Mstislav Rostropovich, who committed it to memory in four days. He premiered it on October 4, 1959, at the Large Hall of the Leningrad Conservatory with the Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Yevgeny Mravinsky. The first recording was made in two days following the premiere by Rostropovich and the Moscow Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by Aleksandr Gauk.

Dmitri Shostakovich wrote his Cello Concerto No. 2, Op. 126, in 1966 in the Crimea. Like the first concerto, it was written for Mstislav Rostropovich, who gave the premiere in Moscow under Yevgeny Svetlanov on 25 September 1966 at the composer's 60th birthday concert. The concerto is sometimes listed as in the key of G, but the score gives no such indication.

The Violin Concerto No. 1 in A minor, Op. 77, was originally composed by Dmitri Shostakovich in 1947–48. He was still working on the piece at the time of the Zhdanov Doctrine, and it could not be performed in the period following the composer's denunciation. In the time between the work's initial completion and the first performance, the composer, sometimes with the collaboration of its dedicatee, David Oistrakh, worked on several revisions. The concerto was finally premiered by the Leningrad Philharmonic under Yevgeny Mravinsky on 29 October 1955. It was well-received, Oistrakh remarking on the "depth of its artistic content" and describing the violin part as a "pithy 'Shakespearian' role."

The Symphony No. 2 in D major, Op. 43, is a four-movement work for orchestra written from 1901 to 1902 by the Finnish composer Jean Sibelius.

The Symphony No. 5 in E-flat major, Op. 82, is a three-movement work for orchestra written from 1914 to 1915 by the Finnish composer Jean Sibelius. He revised it in 1916 and again from 1917 to 1919, at which point it reached its final form.

The Symphony No. 3 in C major, Op. 52, is a three-movement work for orchestra written from 1904 to 1907 by the Finnish composer Jean Sibelius.

Piano Concerto No. 2 in F major, Op. 102, by Dmitri Shostakovich was composed in 1957 for the 19th birthday of his son Maxim, who premiered the piece during his graduation concert at the Moscow Conservatory. It contains many similar elements to Shostakovich's Concertino for Two Pianos: both works were written to be accessible for developing young pianists. It is an uncharacteristically cheerful piece, much more so than most of Shostakovich's works.

Dmitri Shostakovich's String Quartet No. 10 in A-flat major, Op. 118, was composed from 9 to 20 July 1964. It was premiered by the Beethoven Quartet in Moscow and is dedicated to composer Mieczysław (Moisei) Weinberg, a close friend of Shostakovich. It has been described as cultivating the uncertain mood of his earlier Stalin-era quartets, as well as foreshadowing the austerity and emotional distance of his later works. The quartet typified the preference for chamber music over large scale works, such as symphonies, that characterised his late period. According to musicologist Richard Taruskin, this made him the first Russian composer to devote so much time to the string quartet medium.

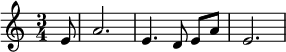

DSCH is a musical motif used by the composer Dmitri Shostakovich to represent himself. It is a musical cryptogram in the manner of the BACH motif, consisting of the notes D, E-flat, C, B natural, or in German musical notation D, Es, C, H, thus standing for the composer's initials in German transliteration: D. Sch..

Alexander Glazunov composed his Symphony No. 3 in D major, Op. 33, in 1890, and it was published by 1892 by the Leipzig firm owned by Mitrofan Belyayev. The symphony is dedicated to Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky and was first performed in St. Petersburg in December 1890 under the baton of Anatoly Lyadov. The symphony is considered a transitional work, with Glazunov largely eschewing the influences of Balakirev, Borodin, and Rimsky-Korsakov inherent in his earlier symphonies for the newer influences of Tchaikovsky and Wagner. Because of this change, the Third has been called the "anti-kuchkist" symphony in Glazunov's output. He would tone down these new influences in his subsequent symphonies as he strove for an eclectic mature style. The Third also shows a greater depth of expression, most evident in the chromatic turns of its third movement, reminiscent of Wagner's opera Tristan und Isolde.

Symphony No. 6 by Russian composer Alfred Schnittke was composed in 1992. It was commissioned by cellist and conductor Mstislav Rostropovich and the National Symphony Orchestra of Washington, who together gave its first performance in Moscow on 25 September 1993.

Aida Huseynova was a musicologist, pianist, and ethnomusicologist from Azerbaijan.