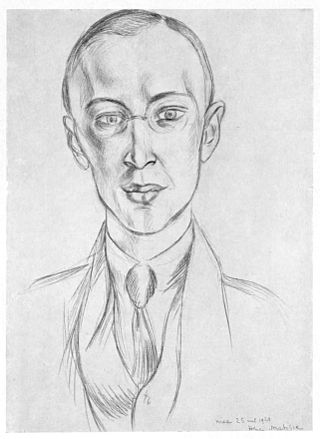

Sergei Sergeyevich Prokofiev was a Russian composer, pianist, and conductor who later worked in the Soviet Union. As the creator of acknowledged masterpieces across numerous music genres, he is regarded as one of the major composers of the 20th century. His works include such widely heard pieces as the March from The Love for Three Oranges, the suite Lieutenant Kijé, the ballet Romeo and Juliet—from which "Dance of the Knights" is taken—and Peter and the Wolf. Of the established forms and genres in which he worked, he created—excluding juvenilia—seven completed operas, seven symphonies, eight ballets, five piano concertos, two violin concertos, a cello concerto, a symphony-concerto for cello and orchestra, and nine completed piano sonatas.

Yevgeny Aleksandrovich Mravinsky was a Soviet and Russian conductor, pianist, and music pedagogue; he was a professor at Leningrad State Conservatory.

Dmitri Shostakovich composed his Symphony No. 4 in C minor, Op. 43, between September 1935 and May 1936, after abandoning some preliminary sketch material. In January 1936, halfway through this period, Pravda—under direct orders from Joseph Stalin—published an editorial "Muddle Instead of Music" that denounced the composer and targeted his opera Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk. Despite this attack and the political climate of the time, Shostakovich completed the symphony and planned its premiere for December 1936 in Leningrad. After rehearsals began, the orchestra's management cancelled the performance, offering a statement that Shostakovich had withdrawn the work. He may have agreed to withdraw it to relieve orchestra officials of responsibility. The symphony was premiered on 30 December 1961 by the Moscow Philharmonic Orchestra led by Kirill Kondrashin.

The Symphony No. 5 in D minor, Op. 47, by Dmitri Shostakovich is a work for orchestra composed between April and July 1937. Its first performance was on November 21, 1937, in Leningrad by the Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra under Yevgeny Mravinsky. The premiere was a "triumphal success" that appealed to both the public and official critics, receiving an ovation that lasted well over half an hour.

The Symphony No. 6 in B minor, Op. 54 by Dmitri Shostakovich was written in 1939, and first performed in Leningrad on November 5, 1939 by the Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra under Yevgeny Mravinsky.

The Symphony No. 9 in E-flat major, Op. 70, was composed by Dmitri Shostakovich in 1945. It was premiered on 3 November 1945 in Leningrad by the Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra under Yevgeny Mravinsky.

The Violin Concerto No. 1 in A minor, Op. 77, was originally composed by Dmitri Shostakovich in 1947–48. He was still working on the piece at the time of the Zhdanov Doctrine, and it could not be performed in the period following the composer's denunciation. In the time between the work's initial completion and the first performance, the composer, sometimes with the collaboration of its dedicatee, David Oistrakh, worked on several revisions. The concerto was finally premiered by the Leningrad Philharmonic under Yevgeny Mravinsky on 29 October 1955. It was well-received, Oistrakh remarking on the "depth of its artistic content" and describing the violin part as a "pithy 'Shakespearian' role."

The Song of the Forests, Op. 81, is an oratorio by Dmitri Shostakovich composed in the summer of 1949. It was written to celebrate the forestation of the Russian steppes following the end of World War II. The composition was essentially made to please Joseph Stalin and the oratorio is notorious for lines praising him as the "great gardener", although performances after Stalin's death have normally omitted them. Premiered by the Leningrad Philharmonic under Yevgeny Mravinsky on 15 November 1949, the work was well received by the government, earning the composer a Stalin Prize the following year.

Sergei Prokofiev's Symphony No. 4 is actually two works, both using material created for The Prodigal Son ballet. The first, Op. 47, was completed in 1930 and premiered that November; it lasts about 22 minutes. The second, Op. 112, is too different to be termed a "revision"; made in 1947, it is about 37 minutes long, differs stylistically from the earlier work, reflecting a new context, and differs formally as well in its grander instrumentation. Accordingly there are two discussions.

Romeo and Juliet, Op. 64, is a ballet by Sergei Prokofiev based on William Shakespeare's play Romeo and Juliet. First composed in 1935, it was substantially revised for its Soviet premiere in early 1940. Prokofiev made from the ballet three orchestral suites and a suite for solo piano.

Sergei Prokofiev set to work on his Piano Concerto No. 2 in G minor, Op. 16, in 1912 and completed it the next year. However, that version of the concerto is lost; the score was destroyed in a fire following the Russian Revolution. Prokofiev reconstructed the work in 1923, two years after finishing his Piano Concerto No. 3, and declared it to be "so completely rewritten that it might almost be considered [Piano Concerto] No. 4." Indeed its orchestration has features that clearly postdate the 1921 concerto. Performing as soloist, Prokofiev premiered this "No. 2" in Paris on 8 May 1924 with Serge Koussevitzky conducting. It is dedicated to the memory of Maximilian Schmidthof, a friend of Prokofiev's at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory, who had committed suicide in April 1913 after having written a farewell letter to Prokofiev.

Sergei Prokofiev composed and compiled his Waltz Suite, Op. 110, during the Soviet Union's post-Great Patriotic War period of 1946–1947.

Sergei Prokofiev wrote the symphonic suite The Year 1941 in 1941.

Sergei Prokofiev's Lieutenant Kijé music was originally written to accompany the film of the same name, produced by the Belgoskino film studios in Leningrad in 1933–34 and released in March 1934. It was Prokofiev's first attempt at film music, and his first commission.

The Story of a Real Man is an opera in four acts by the Russian composer Sergei Prokofiev, his opus 117. It was written from 1947 to 1948, and was his last opera.

Konstantin Saradzhev was an Armenian conductor and violinist. He was an advocate of new Russian music, and conducted a number of premieres of works by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Modest Mussorgsky, Igor Stravinsky, Sergei Prokofiev, Nikolai Myaskovsky, Dmitri Shostakovich, and Aram Khachaturian. His son Konstantin Konstantinovich Saradzhev was a noted bell ringer and musical theorist.

Lina Ivanovna Prokofieva, born Carolina Codina Nemísskaia, was a Spanish singer and the first wife of Russian composer Sergei Prokofiev. They married in 1923. Despite misgivings about her husband's decision to move to the Soviet Union, she settled there with him in 1936. They separated in 1941. In 1948, their marriage was ruled null and void, a verdict that was upheld in 1958 by the Supreme Court of the USSR. Her stage name was Lina Llubera.

Mariya-Cecilia Abramovna Mendelson-Prokofieva, typically referred to as Mira Mendelson, was a Russian poet, writer, and translator who was the second wife of the composer Sergei Prokofiev. She was the co-librettist of her husband's operas Betrothal in a Monastery, The Story of a Real Man, and War and Peace, as well as the ballet The Tale of the Stone Flower.

October, Op. 131, is a symphonic poem composed by Dmitri Shostakovich to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of the October Revolution in 1967. He was spurred to compose the work after reencountering his score for the Vasilyev brothers' 1937 film Volochayev Days, reusing its "Partisan Song" in October. Although Shostakovich completed the work quickly, the process of writing it fatigued him physically because of his deteriorating motor functions.

On Guard for Peace, also translated as On Guard of Peace, Op. 124 is an oratorio by Sergei Prokofiev scored for narrators, mezzo-soprano, boy soprano, boys choir, mixed choir, and symphony orchestra. Each of its ten movements sets texts by Samuil Marshak, who had collaborated previously with the composer in the work Winter Bonfire, Op. 122.