Mansa Musa was the ninth Mansa of the Mali Empire, which reached its territorial peak during his reign. Musa's reign is often regarded as the zenith of Mali's power and prestige.

The Songhai people are an ethnolinguistic group in West Africa who speak the various Songhai languages. Their history and lingua franca is linked to the Songhai Empire which dominated the western Sahel in the 15th and 16th century. Predominantly adherents of Islam, the Songhai are primarily located in Niger and Mali within the Western Sudanic region. Historically, the term "Songhai" did not denote an ethnic or linguistic identity but referred to the ruling caste of the Songhay Empire known as the Songhaiborai. However, the correct term used to refer to this group of people collectively by the natives is "Ayneha". Although some Speakers in Mali have also adopted the name Songhay as an ethnic designation, other Songhay-speaking groups identify themselves by other ethnic terms such as Zarma or Isawaghen. The dialect of Koyraboro Senni spoken in Gao is unintelligible to speakers of the Zarma dialect of Niger, according to at least one report. The Songhay languages are commonly taken to be Nilo-Saharan but this classification remains controversial: Dimmendaal (2008) believes that for now it is best considered an independent language family.

Askia Muhammad I (1443–1538), born Muhammad ibn Abi Bakr al-Turi or Muhammad Ture, was the first ruler of the Askia dynasty of the Songhai Empire, reigning from 1493 to 1528. He is also known as Askia the Great, and his name in modern Songhai is Mamar Kassey. Askia Muhammad strengthened his empire and made it the largest empire in West Africa's history. At its peak under his reign, the Songhai Empire encompassed the Hausa states as far as Kano and much of the territory that had belonged to the Songhai empire in the east. His policies resulted in a rapid expansion of trade with Europe and Asia, the creation of many schools, and the establishment of Islam as an integral part of the empire.

Sunni Ali, also known as Si Ali, Sunni Ali Ber, reigned from about 1464 to 1492 as the 15th ruler of the Sunni dynasty of the Songhai Empire. He transformed the relatively small state into an empire by conquering Timbuktu, Massina, the Inner Niger Delta, and Djenne.

Gao, or Gawgaw/Kawkaw, is a city in Mali and the capital of the Gao Region. The city is located on the River Niger, 320 km (200 mi) east-southeast of Timbuktu on the left bank at the junction with the Tilemsi valley.

Koumbi Saleh, or Kumbi Saleh, is the site of a ruined ancient and medieval city in south east Mauritania that may have been the capital of the Ghana Empire. It is also a commune with a population of 11,064.

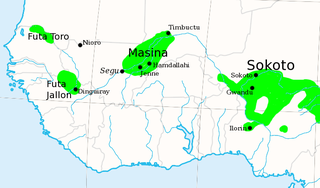

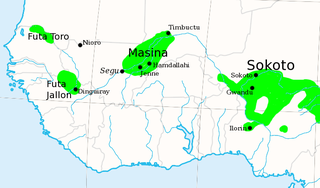

The Caliphate of Hamdullahi, commonly known as the Massina empire, was an early nineteenth-century Sunni Muslim caliphate in West Africa centered in the Inner Niger Delta of what is now the Mopti and Ségou Regions of Mali. It was founded by Seku Amadu in 1818 during the Fulani jihads after defeating the Bambara Empire and its allies at the Battle of Noukouma. By 1853, the empire had fallen into decline and was ultimately destroyed by Omar Saidou Tall of Toucouleur.

Sheikhu Ahmadu was the Fulbe founder of the Massina Empire in the Inner Niger Delta, now the Mopti Region of Mali. He ruled as Almami from 1818 until his death in 1845, also taking the title Cisse al-Masini.

Askia Mohammad Benkan, also Askiya Muhammad Bonkana Kirya, was the third ruler of the Songhai Empire from 1531 to 1537.

The Zā dynasty were rulers of the Gao Empire based in the towns of Kukiya and Gao on the Niger River in what is today modern Mali. The Songhai people are descended from this kingdom and the Zarma people of Niger derive their name, which means "the descendants of Za", from this dynasty.

The Sonni dynasty, Sunni dynasty or Si dynasty was a dynasty of rulers of the Songhai Empire of medieval West Africa. The origins of the dynasty are shrouded in legend and debated by historians. The last ruler, Sonni Baru, ruled until 1493 when the throne was usurped by the Askiya Muhammad I, the founder of the Askiya dynasty.

The Askiya dynasty, also known as the Askia dynasty, ruled the Songhai Empire at the height of that state's power. It was founded in 1493 by Askia Mohammad I, a general of the Songhai Empire who usurped the Sonni dynasty. The Askiya ruled from Gao over the vast Songhai Empire until its defeat by a Moroccan invasion force in 1591. After the defeat, the dynasty moved south back to its homeland and created several smaller kingdoms in what is today Songhai in south-western Niger and further south in the Dendi.

The Tarikh al-Sudan is a West African chronicle written in Arabic in around 1655 by the chronicler of Timbuktu, al-Sa'di. It provides the single most important primary source for the history of the Songhay Empire. It and the Tarikh al-fattash, another 17th century chronicle giving a history of Songhay, are together known as the Timbuktu Chronicles.

The University of Timbuktu is a collective term for the teaching associated with three mosques in the city of Timbuktu in what is now Mali: the mosques of Sankore, Djinguereber, and Sidi Yahya. It was an organized scholastic community that endured for many centuries during the medieval period. The university contributed to the modern understanding of Islamic and academic studies in West Africa during the medieval period and produced a number of scholars and manuscripts taught under the Maliki school of thought.

The Ghana Empire, also known as simply Ghana, Ghanata, or Wagadou, was a West African classical to post-classical era western-Sahelian empire based in the modern-day southeast of Mauritania and western Mali.

The Gao Empire was a powerful kingdom that ruled the Niger bend from approximately the 7th century CE until their fall to the Mali Empire in the late 14th century. Ruled by the Za dynasty from the capital of Gao, the empire was an important predecessor of the Songhai Empire.

Starting out as a seasonal settlement, Timbuktu was in the kingdom of Mali when it became a permanent settlement early in the 12th century. After a shift in trading routes, the town flourished from the trade in salt, gold, ivory and slaves from several towns and states such as Begho of Bonoman, Sijilmassa, and other Saharan cities. It became part of the Mali Empire early in the 14th century. By this time it had become a major centre of learning in the area. In the first half of the 15th century the Tuareg tribes took control of the city for a short period until the expanding Songhai Empire absorbed the city in 1468. The Moroccan army defeated the Songhai in 1591, and made Timbuktu, rather than Gao, their capital.

Timbuktu Chronicles is the collective name for a group of writings created in Timbuktu in the second half of the 17th century. They form a distinct genre of taʾrīkh (history). There are three surviving works and a probable lost one.

West African manuscripts are abundant and diverse in content and form, such as books, documents, and letters, and are composed in the Arabic script, Ajami script, and indigenous African scripts. West African manuscripts, as dialogical products of West African manuscript culture and components of West African intellectual history, may have been produced as early as the 10th century CE. West African Muslim scholars, who were bilingual or multilingual and constituted what is collectively a West African intelligentsia that shaped West African historiography, composed the majority of West African manuscripts. West African countries with manuscripts from the precolonial, colonial, and postcolonial periods include Togo, Sierra Leone, Senegal, Nigeria, Niger, Mauritania, Mali, Guinea, Ghana, Gambia, Ivory Coast, Cameroon, Burkina Faso, and Benin. The Timbuktu manuscripts in Timbuktu, Mali, which are the most well known set of manuscripts in West Africa, are estimated in number to total between 101,820 manuscripts and 348,531 manuscripts.

The Battle of Noukouma was fought on 21 March 1818 between a small force of jihadists led by Seku Amadu and a Bamana force led by General Jamogo Séri. It was the first and most significant battle of Seku Amdadu's jihad and saw an unexpected jihadist victory against the numerically superior Bamana army. The victory was interpreted as a divine miracle by many and allowed Seku Amadu to rapidly expand his army to over 40,000.