Muskogean is a Native American language family spoken in different areas of the Southeastern United States. Though the debate concerning their interrelationships is ongoing, the Muskogean languages are generally divided into two branches, Eastern Muskogean and Western Muskogean. Typologically, Muskogean languages are agglutinative. One documented language, Apalachee, is extinct and the remaining languages are critically endangered.

The Icafui people were a Timucua people of southeastern Georgia, who were closely related if not synonymous with the Cascangue people. Exceptionally little is known about the Icafui, other than their general location and the fact that they spoke a dialect of Timucua called "Itafi" along with the Ibi.

Timucua is a language isolate formerly spoken in northern and central Florida and southern Georgia by the Timucua peoples. Timucua was the primary language used in the area at the time of Spanish colonization in Florida. Differences among the nine or ten Timucua dialects were slight, and appeared to serve mostly to delineate band or tribal boundaries. Some linguists suggest that the Tawasa of what is now northern Alabama may have spoken Timucua, but this is disputed.

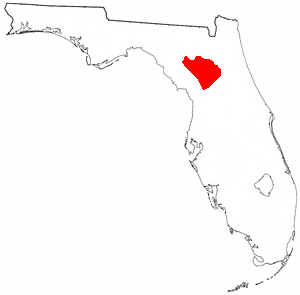

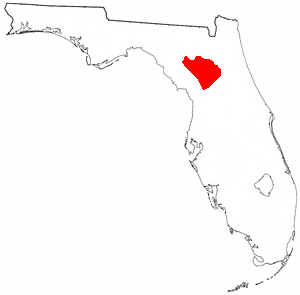

The Potano tribe lived in north-central Florida at the time of first European contact. Their territory included what is now Alachua County, the northern half of Marion County and the western part of Putnam County. This territory corresponds to that of the Alachua culture, which lasted from about 700 until 1700. The Potano were among the many tribes of the Timucua people, and spoke a dialect of the Timucua language.

The Mocama were a Native American people who lived in the coastal areas of what are now northern Florida and southeastern Georgia. A Timucua group, they spoke the dialect known as Mocama, the best-attested dialect of the Timucua language. Their heartland extended from about the Altamaha River in Georgia to south of the mouth of the St. John's River, covering the Sea Islands and the inland waterways, Intracoastal. and much of present-day Jacksonville. At the time of contact with Europeans, there were two major chiefdoms among the Mocama, the Saturiwa and the Tacatacuru, each of which evidently had authority over multiple villages. The Saturiwa controlled chiefdoms stretching to modern day St. Augustine, but the native peoples of these chiefdoms have been identified by Pareja as speaking Agua Salada, which may have been a distinct dialect.

The Wakulla River is an 11-mile-long (18 km) river in Wakulla County, Florida. It carries the outflow from Wakulla Springs, site of the Edward Ball Wakulla Springs State Park, to the St. Marks River 3 miles (5 km) north of the Gulf of Mexico. Its drainage basin extends northwest into Leon County, including Munson Slough, and may extend as far north as the Georgia border.

The Chisca were a tribe of Native Americans living in present-day eastern Tennessee and southwestern Virginia in the 16th century. Their descendants, the Yuchi lived in present-day Alabama, Georgia, and Florida in the 17th, 18th, and early 19th centuries, and were removed to Indian Territory in the 1830s.

The Chacatos were a Native American people who lived in the upper Apalachicola River and Chipola River basins in what is now Florida in the 17th century. The Spanish established two missions in Chacato villages in 1674. As a result of attempts by the missionaries to impose full observance of Christian rites and morals on the newly converted Chacatos, many of them rebelled, trying to murder one of the missionaries. Many of the rebels fled to Tawasa, while others joined the Chiscas, who had become openly hostile to the Spanish. Other Chacatos moved to missions in or closer to Apalachee Province, abandoning their villages west of the Apalachicola River.

The Ofo language is a language formerly spoken by the Ofo people, also called the Mosopelea, in what is now Ohio, along the Ohio River, until about 1673. The tribe moved south along the Mississippi River to Mississippi, near the Natchez people, and then to Louisiana, settling near the Tunica.

Acuera was the name of both an indigenous town and a province or region in central Florida during the 16th and 17th centuries. The indigenous people of Acuera spoke a dialect of the Timucua language. In 1539 the town first encountered Europeans when it was raided by soldiers of Hernando de Soto's expedition. French colonists also knew this town during their brief tenure (1564–1565) in northern Florida.

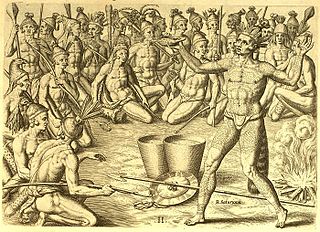

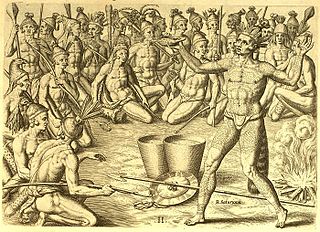

The Timucua were a Native American people who lived in Northeast and North Central Florida and southeast Georgia. They were the largest indigenous group in that area and consisted of about 35 chiefdoms, many leading thousands of people. The various groups of Timucua spoke several dialects of the Timucua language. At the time of European contact, Timucuan speakers occupied about 19,200 square miles (50,000 km2) in the present-day states of Florida and Georgia, with an estimated population of 200,000. Milanich notes that the population density calculated from those figures, 10.4 per square mile (4.0/km2) is close to the population densities calculated by other authors for the Bahamas and for Hispaniola at the time of first European contact. The territory occupied by Timucua speakers stretched from the Altamaha River and Cumberland Island in present-day Georgia as far south as Lake George in central Florida, and from the Atlantic Ocean west to the Aucilla River in the Florida Panhandle, though it reached the Gulf of Mexico at no more than a couple of points.

Warao is the native language of the Warao people. A language isolate, it is spoken by about 33,000 people primarily in northern Venezuela, Guyana and Suriname. It is notable for its unusual object–subject–verb word order. The 2015 Venezuelan film Gone with the River was spoken in Warao.

Mocoso was the name of a 16th-century chiefdom located on the east side of Tampa Bay, Florida near the mouth of the Alafia River, of its chief town and of its chief. Mocoso was also the name of a 17th-century village in the province of Acuera, a branch of the Timucua. The people of both villages are believed to have been speakers of the Timucua language.

The Saturiwa were a Timucua chiefdom centered on the mouth of the St. Johns River in what is now Jacksonville, Florida. They were the largest and best attested chiefdom of the Timucua subgroup known as the Mocama, who spoke the Mocama dialect of Timucuan and lived in the coastal areas of present-day northern Florida and southeastern Georgia. They were a prominent political force in the early days of European settlement in Florida, forging friendly relations with the French Huguenot settlers at Fort Caroline in 1564 and later becoming heavily involved in the Spanish mission system.

The Agua Dulce or Agua Fresca (Freshwater) were a Timucua people of northeastern Florida. They lived in the St. Johns River watershed north of Lake George, and spoke a dialect of the Timucua language also known as Agua Dulce.

The Northern Utina, also known as the Timucua or simply Utina, were a Timucua people of northern Florida. They lived north of the Santa Fe River and east of the Suwannee River, and spoke a dialect of the Timucua language known as "Timucua proper". They appear to have been closely associated with the Yustaga people, who lived on the other side of the Suwannee. The Northern Utina represented one of the most powerful tribal units in the region in the 16th and 17th centuries, and may have been organized as a loose chiefdom or confederation of smaller chiefdoms. The Fig Springs archaeological site may be the remains of their principal village, Ayacuto, and the later Spanish mission of San Martín de Timucua.

The Ibi, also known as the Yui or Ibihica, were a Timucua chiefdom in the present-day U.S. state of Georgia during the 16th and 17th centuries. They lived in southeastern Georgia, about 50 miles from the coast. Like their neighbors, the Icafui tribe, they spoke a dialect of the Timucua language called Itafi.

The Yustaga were a Timucua people of what is now northwestern Florida during the 16th and 17th centuries. The westernmost Timucua group, they lived between the Aucilla and Suwannee Rivers in the Florida Panhandle, just east of the Apalachee people. A dominant force in regional tribal politics, they may have been organized as a loose regional chiefdom consisting of up to eight smaller local chiefdoms.

Urriparacoxi, or Paracoxi, was the chief of a Native American group in central Florida at the time of Hernando de Soto's expedition through what is now the southeastern United States. "Urriparacoxi" was a title, meaning "war leader". There is no known name for the people he led, or for their territory.

The Tawasa Indian Tribe, also known as the Alibamu Indian Tribe, was located near the Alabama River, in Autauga County, Alabama. The population of the tribe was known to be around 330 members, all living in or near what were known as the Tawasa and Autauga Towns. The tribe existed around the late 1600s, early 1700s, however somewhat disappeared in the early 1700s, due to violence and flee. The tribe was split, with around 60 members joining the Alabama tribe, at Fort Toulouse. Some time later, the tribe at Fort Toulouse migrated south joining various tribes in Florida. For the remaining count, there is little evidence to show where they all went, however there is evidence to show that some ended up in Oklahoma, along with some Creeks who migrated there.