The Permian Basin is a large sedimentary basin in the southwestern part of the United States. It is the highest producing oil field in the United States, producing an average of 4.2 million barrels of crude oil per day in 2019. This sedimentary basin is located in western Texas and southeastern New Mexico. It reaches from just south of Lubbock, past Midland and Odessa, south nearly to the Rio Grande River in southern West Central Texas, and extending westward into the southeastern part of New Mexico. It is so named because it has one of the world's thickest deposits of rocks from the Permian geologic period. The greater Permian Basin comprises several component basins; of these, the Midland Basin is the largest, Delaware Basin is the second largest, and Marfa Basin is the smallest. The Permian Basin covers more than 86,000 square miles (220,000 km2), and extends across an area approximately 250 miles (400 km) wide and 300 miles (480 km) long.

An alluvial fan is an accumulation of sediments that fans outwards from a concentrated source of sediments, such as a narrow canyon emerging from an escarpment. They are characteristic of mountainous terrain in arid to semiarid climates, but are also found in more humid environments subject to intense rainfall and in areas of modern glaciation. They range in area from less than 1 square kilometer (0.4 sq mi) to almost 20,000 square kilometers (7,700 sq mi).

The geology of the Zion and Kolob canyons area includes nine known exposed formations, all visible in Zion National Park in the U.S. state of Utah. Together, these formations represent about 150 million years of mostly Mesozoic-aged sedimentation in that part of North America. Part of a super-sequence of rock units called the Grand Staircase, the formations exposed in the Zion and Kolob area were deposited in several different environments that range from the warm shallow seas of the Kaibab and Moenkopi formations, streams and lakes of the Chinle, Moenave, and Kayenta formations to the large deserts of the Navajo and Temple Cap formations and dry near shore environments of the Carmel Formation.

The Los Angeles Basin is a sedimentary basin located in Southern California, in a region known as the Peninsular Ranges. The basin is also connected to an anomalous group of east-west trending chains of mountains collectively known as the Transverse Ranges. The present basin is a coastal lowland area, whose floor is marked by elongate low ridges and groups of hills that is located on the edge of the Pacific Plate. The Los Angeles Basin, along with the Santa Barbara Channel, the Ventura Basin, the San Fernando Valley, and the San Gabriel Basin, lies within the greater Southern California region. The majority of the jurisdictional land area of the city of Los Angeles physically lies within this basin.

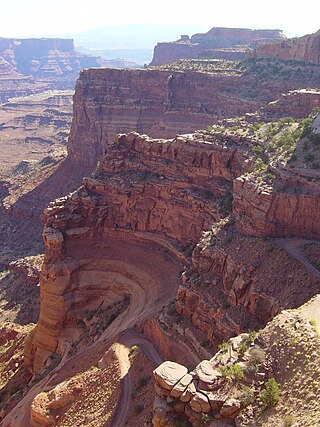

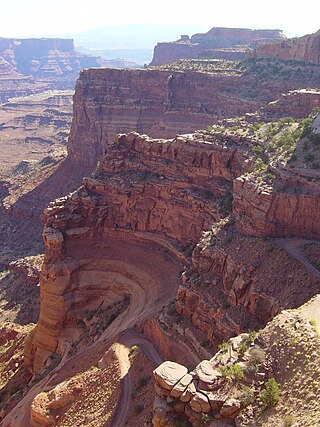

The exposed geology of the Canyonlands area is complex and diverse; 12 formations are exposed in Canyonlands National Park that range in age from Pennsylvanian to Cretaceous. The oldest and perhaps most interesting was created from evaporites deposited from evaporating seawater. Various fossil-rich limestones, sandstones, and shales were deposited by advancing and retreating warm shallow seas through much of the remaining Paleozoic.

The exposed geology of the Death Valley area presents a diverse and complex set of at least 23 formations of sedimentary units, two major gaps in the geologic record called unconformities, and at least one distinct set of related formations geologists call a group. The oldest rocks in the area that now includes Death Valley National Park are extensively metamorphosed by intense heat and pressure and are at least 1700 million years old. These rocks were intruded by a mass of granite 1400 Ma and later uplifted and exposed to nearly 500 million years of erosion.

The Dallas–Fort Worth Metroplex sits above Cretaceous-age strata ranging from ≈145-66 Ma. These Cretaceous-aged sediments lie above the eroded Ouachita Mountains and the Fort Worth Basin, which was formed by the Ouachita Orogeny. Going from west to east in the DFW Metroplex and down towards the Gulf of Mexico, the strata get progressively younger. The Cretaceous sediments dip very gently to the east.

The Molasse basin is a foreland basin north of the Alps which formed during the Oligocene and Miocene epochs. The basin formed as a result of the flexure of the European plate under the weight of the orogenic wedge of the Alps that was forming to the south.

A foreland basin is a structural basin that develops adjacent and parallel to a mountain belt. Foreland basins form because the immense mass created by crustal thickening associated with the evolution of a mountain belt causes the lithosphere to bend, by a process known as lithospheric flexure. The width and depth of the foreland basin is determined by the flexural rigidity of the underlying lithosphere, and the characteristics of the mountain belt. The foreland basin receives sediment that is eroded off the adjacent mountain belt, filling with thick sedimentary successions that thin away from the mountain belt. Foreland basins represent an endmember basin type, the other being rift basins. Space for sediments is provided by loading and downflexure to form foreland basins, in contrast to rift basins, where accommodation space is generated by lithospheric extension.

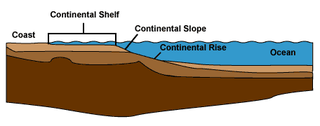

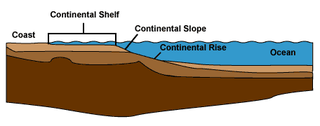

The continental rise is a low-relief zone of accumulated sediments that lies between the continental slope and the abyssal plain. It is a major part of the continental margin, covering around 10% of the ocean floor.

The Coyote Mountains are a small mountain range in San Diego and Imperial Counties in southern California. The Coyotes form a narrow ESE trending 2 mi (3.2 km) wide range with a length of about 12 mi (19 km). The southeast end turns and forms a 2 mi (3.2 km) north trending "hook". The highest point is Carrizo Mountain on the northeast end with an elevation of 2,408 feet (734 m). Mine Peak at the northwest end of the range has an elevation of 1,850 ft (560 m). Coyote Wash along I-8 along the southeast margin of the range is 100 to 300 feet in elevation. Plaster City lies in the Yuha Desert about 5.5 mi (8.9 km) east of the east end of the range.

The Aquitaine Basin is the second largest Mesozoic and Cenozoic sedimentary basin in France after the Paris Basin, occupying a large part of the country's southwestern quadrant. Its surface area covers 66,000 km2 onshore. It formed on Variscan basement which was peneplained during the Permian and then started subsiding in the early Triassic. The basement is covered in the Parentis Basin and in the Subpyrenean Basin—both sub-basins of the main Aquitaine Basin—by 11,000 m of sediment.

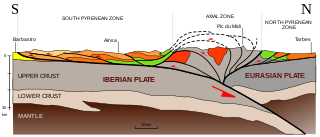

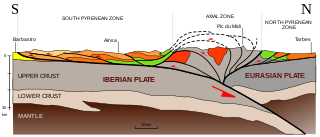

The Pyrenees are a 430-kilometre-long, roughly east–west striking, intracontinental mountain chain that divide France, Spain, and Andorra. The belt has an extended, polycyclic geological evolution dating back to the Precambrian. The chain's present configuration is due to the collision between the microcontinent Iberia and the southwestern promontory of the European Plate. The two continents were approaching each other since the onset of the Upper Cretaceous (Albian/Cenomanian) about 100 million years ago and were consequently colliding during the Paleogene (Eocene/Oligocene) 55 to 25 million years ago. After its uplift, the chain experienced intense erosion and isostatic readjustments. A cross-section through the chain shows an asymmetric flower-like structure with steeper dips on the French side. The Pyrenees are not solely the result of compressional forces, but also show an important sinistral shearing.

The Himalayan foreland basin is an active collisional foreland basin system in South Asia. Uplift and loading of the Eurasian Plate on to the Indian Plate resulted in the flexure (bending) of the Indian Plate, and the creation of a depression adjacent to the Himalayan mountain belt. This depression was filled with sediment eroded from the Himalaya, that lithified and produced a sedimentary basin ~3 to >7 km deep. The foreland basin spans approximately 2,000 kilometres (1,200 mi) in length and 450 kilometres (280 mi) in width. From west to east the foreland basin stretches across five countries: Pakistan, India, Nepal, Bangladesh, and Bhutan.

The Tarfaya Basin is a structural basin located in southern Morocco that extends westward into the Moroccan territorial waters in the Atlantic Ocean. The basin is named for the city of Tarfaya located near the border of Western Sahara, a region governed by the Kingdom of Morocco. The Canary Islands form the western edge of the basin and lie approximately 100 km to the west.

The geology of Kyrgyzstan began to form during the Proterozoic. The country has experienced long-running uplift events, forming the Tian Shan mountains and large, sediment filled basins.

The Junggar Basin, also known as the Dzungarian Basin or Zungarian Basin, is one of the largest sedimentary basins in Northwest China. It is located in Dzungaria in northern Xinjiang, and enclosed by the Tarbagatai Mountains of Kazakhstan in the northwest, the Altai Mountains of Mongolia in the northeast, and the Heavenly Mountains in the south. The geology of Junggar Basin mainly consists of sedimentary rocks underlain by igneous and metamorphic basement rocks. The basement of the basin was largely formed during the development of the Pangea supercontinent during complex tectonic events from Precambrian to late Paleozoic time. The basin developed as a series of foreland basins – in other words, basins developing immediately in front of growing mountain ranges – from Permian time to the Quaternary period. The basin's preserved sedimentary records show that the climate during the Mesozoic era was marked by a transition from humid to arid conditions as monsoonal climatic effects waned. The Junggar basin is rich in geological resources due to effects of volcanism and sedimentary deposition. According to Guinness World Records it is a land location remotest from open sea with great-circle distance of 2,648 km from the nearest open sea at 46°16′8″N86°40′2″E.

The Hornelen Basin is a sedimentary basin in Vestland, Norway, containing an estimated 25 km stratigraphic thickness of coarse clastic sedimentary rocks of Devonian age. It forms part of a group of basins of similar age along the west coast of Norway between Sognefjord and Nordfjord, related to movement on the Nordfjord-Sogn Detachment. It formed as a result of extensional tectonics as part of the post-orogenic collapse of crust that was thickened during the Caledonian Orogeny towards the end of the Silurian period. It is named for the mountain Hornelen on the northern margin of the basin.

The Aksu Basin is a sedimentary basin in southwestern Turkey, around the present-day Aksu River. Located at the intersection of several major tectonic systems, in the Isparta Angle, the Aksu Basin covers an area of some 2000 square kilometers. Together with the Köprü Çay Basin and the Manavgat Basin, the Aksu Basin forms part of the broader Antalya Basin. It forms a graben relative to the surrounding Anatolian plateau.