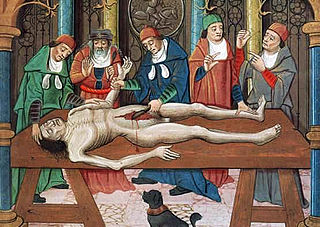

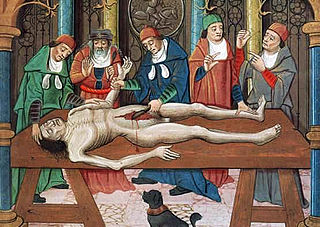

The history of anatomy extends from the earliest examinations of sacrificial victims to the sophisticated analyses of the body performed by modern anatomists and scientists. Written descriptions of human organs and parts can be traced back thousands of years to ancient Egyptian papyri, where attention to the body was necessitated by their highly elaborate burial practices.

Frederik Ruysch was a Dutch botanist and anatomist. He is known for developing techniques for preserving anatomical specimens, which he used to create dioramas or scenes incorporating human parts. His anatomical preparations included over 2,000 anatomical, pathological, zoological, and botanical specimens, which were preserved by either drying or embalming. Ruysch is also known for his proof of valves in the lymphatic system, the vomeronasal organ in snakes, and arteria centralis oculi. He was the first to describe the disease that is today known as Hirschsprung's disease, as well as several pathological conditions, including intracranial teratoma, enchondromatosis, and Majewski syndrome.

Dissection is the dismembering of the body of a deceased animal or plant to study its anatomical structure. Autopsy is used in pathology and forensic medicine to determine the cause of death in humans. Less extensive dissection of plants and smaller animals preserved in a formaldehyde solution is typically carried out or demonstrated in biology and natural science classes in middle school and high school, while extensive dissections of cadavers of adults and children, both fresh and preserved are carried out by medical students in medical schools as a part of the teaching in subjects such as anatomy, pathology and forensic medicine. Consequently, dissection is typically conducted in a morgue or in an anatomy lab.

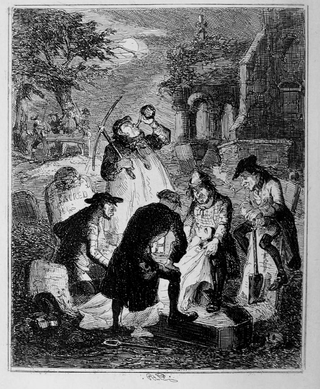

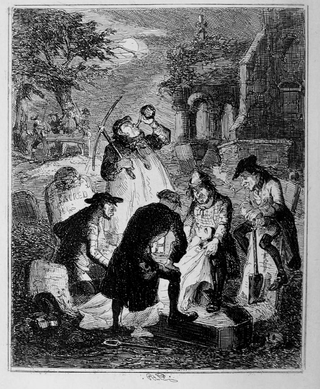

Body snatching is the illicit removal of corpses from graves, morgues, and other burial sites. Body snatching is distinct from the act of grave robbery as grave robbing does not explicitly involve the removal of the corpse, but rather theft from the burial site itself. The term 'body snatching' most commonly refers to the removal and sale of corpses primarily for the purpose of dissection or anatomy lectures in medical schools. The term was coined primarily in regard to cases in the United Kingdom and United States throughout the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. However, there have been cases of body snatching in many countries, with the first recorded case dating back to 1319 in Bologna, Italy.

A prosector is a person with the special task of preparing a dissection for demonstration, usually in medical schools or hospitals. Many important anatomists began their careers as prosectors working for lecturers and demonstrators in anatomy and pathology.

Gross anatomy is the study of anatomy at the visible or macroscopic level. The counterpart to gross anatomy is the field of histology, which studies microscopic anatomy. Gross anatomy of the human body or other animals seeks to understand the relationship between components of an organism in order to gain a greater appreciation of the roles of those components and their relationships in maintaining the functions of life. The study of gross anatomy can be performed on deceased organisms using dissection or on living organisms using medical imaging. Education in the gross anatomy of humans is included training for most health professionals.

Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn, usually simply known as Rembrandt, was a Dutch Golden Age painter, printmaker, and draughtsman. An innovative and prolific master in three media, he is generally considered one of the greatest visual artists in the history of art. It is estimated Rembrandt produced a total of about three hundred paintings, three hundred etchings, and two thousand drawings.

Job van Meekeren was a Dutch surgeon.

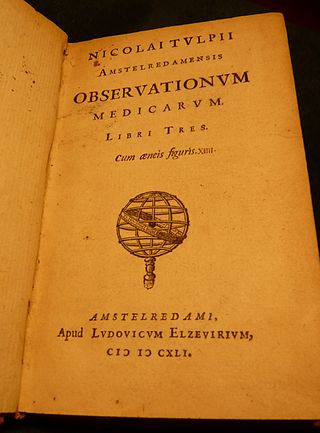

Nicolaes Tulp was a Dutch surgeon and mayor of Amsterdam. Tulp was well known for his upstanding moral character and as the subject of Rembrandt's famous painting The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp.

A cadaver or corpse is a dead human body. Cadavers are used by medical students, physicians and other scientists to study anatomy, identify disease sites, determine causes of death, and provide tissue to repair a defect in a living human being. Students in medical school study and dissect cadavers as a part of their education. Others who study cadavers include archaeologists and arts students. In addition, a cadaver may be used in the development and evaluation of surgical instruments.

The Agnew Clinic is an 1889 oil painting by American artist Thomas Eakins. It was commissioned to honor anatomist and surgeon David Hayes Agnew, on his retirement from teaching at the University of Pennsylvania.

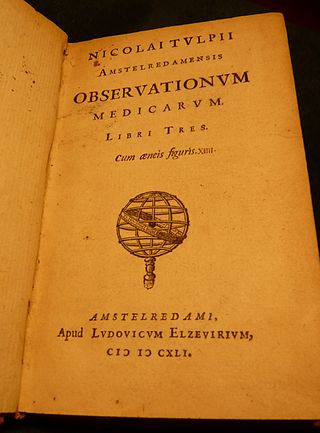

Observationes Medicae is a 1641 book by Nicolaes Tulp. Tulp is primarily famous today for his central role in the 1632 group portrait by Rembrandt of the Amsterdam Guild of Surgeons, which commemorates his appointment as praelector in 1628.

Gunther von Hagens is a German anatomist, businessman and lecturer. He developed the technique for preserving biological tissue specimens called plastination. Von Hagens has organized numerous Body Worlds public exhibitions and occasional live demonstrations of his and his colleagues' work, and has traveled worldwide to promote its educational value. The sourcing of biological specimens for and the commercial background of his exhibits has been controversial.

The Anatomy Lesson (1995) is a novel by John David Morley, inspired by Rembrandt’s painting The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp.

The Anatomy Lesson may refer to:

Resurrectionists were body snatchers who were commonly employed by anatomists in the United Kingdom during the 18th and 19th centuries to exhume the bodies of the recently dead. Between 1506 and 1752 only a very few cadavers were available each year for anatomical research. The supply was increased when, in an attempt to intensify the deterrent effect of the death penalty, Parliament passed the Murder Act 1752. By allowing judges to substitute the public display of executed criminals with dissection, the new law significantly increased the number of bodies anatomists could legally access. This proved insufficient to meet the needs of the hospitals and teaching centres that opened during the 18th century. Corpses and their component parts became a commodity, but although the practice of disinterment was hated by the general public, bodies were not legally anyone's property. The resurrectionists therefore operated in a legal grey area.

The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Deijman is a 1656 fragmentary painting by Rembrandt, now in Amsterdam Museum. It is a group portrait showing a brain dissection by Dr. Jan Deijman (1619–1666). Much of the canvas was destroyed in a fire in 1723 and the painting was subsequently recut to its present dimensions, though a preparatory sketch shows the full group.

The pendant portraits of Maerten Soolmans and Oopjen Coppit are a pair of full-length wedding portraits by Rembrandt. They were painted on the occasion of the marriage of Maerten Soolmans and Oopjen Coppit in 1634. Formerly owned by the Rothschild family, they became jointly owned by the Louvre Museum and the Rijksmuseum in 2015 after both museums managed to contribute half of the purchase price of €160 million, a record for works by Rembrandt.

The 'Finger-Assisted' Nephrectomy of Professor Nadey Hakim and the World Presidents of the International College of Surgeons in Chicago, or, The Wise in Examination of the Torn Contemporary State is a painting by British artist Henry Ward depicting transplant surgeon Nadey Hakim demonstrating the removal of a living donor kidney. It is on display at Başkent University, Ankara, Turkey.