Democritus was an Ancient Greek pre-Socratic philosopher from Abdera, primarily remembered today for his formulation of an atomic theory of the universe.

Laurence Sterne was an Anglo-Irish novelist and Anglican cleric who wrote the novels The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman and A Sentimental Journey Through France and Italy, published sermons and memoirs, and indulged in local politics. He grew up in a military family, travelling mainly in Ireland but briefly in England. An uncle paid for Sterne to attend Hipperholme Grammar School in the West Riding of Yorkshire, as Sterne's father was ordered to Jamaica, where he died of malaria some years later. He attended Jesus College, Cambridge on a sizarship, gaining bachelor's and master's degrees. While Vicar of Sutton-on-the-Forest, Yorkshire, he married Elizabeth Lumley in 1741. His ecclesiastical satire A Political Romance infuriated the church and was burnt.

Melancholia or melancholy is a concept found throughout ancient, medieval, and premodern medicine in Europe that describes a condition characterized by markedly depressed mood, bodily complaints, and sometimes hallucinations and delusions.

Robert Burton was an English author and fellow of Oxford University, who wrote the encyclopedic tome The Anatomy of Melancholy.

Paul Jordan-Smith was an American Universalist minister who also worked as a writer, lecturer and editor. Academically, he is regarded as one of the foremost authorities on the 17th-century British author and scholar Robert Burton. However, he is most well known for originating the hoax art movement Disumbrationism.

Bibliomania can be a symptom of obsessive–compulsive disorder which involves the collecting or even hoarding of books to the point where social relations or health are damaged.

Metafiction is a form of fiction that emphasizes its own narrative structure in a way that inherently reminds the audience that they are reading or viewing a fictional work. Metafiction is self-conscious about language, literary form, and story-telling, and works of metafiction directly or indirectly draw attention to their status as artifacts. Metafiction is frequently used as a form of parody or a tool to undermine literary conventions and explore the relationship between literature and reality, life, and art.

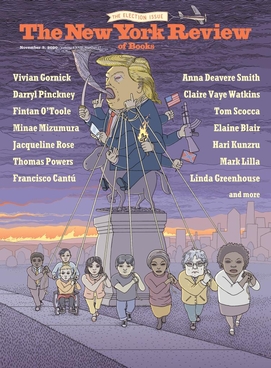

The New York Review of Books is a semi-monthly magazine with articles on literature, culture, economics, science and current affairs. Published in New York City, it is inspired by the idea that the discussion of important books is an indispensable literary activity. Esquire called it "the premier literary-intellectual magazine in the English language." In 1970, writer Tom Wolfe described it as "the chief theoretical organ of Radical Chic".

The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman, also known as Tristram Shandy, is a novel by Laurence Sterne, inspired by Don Quixote. It was published in nine volumes, the first two appearing in 1759, and seven others following over the next seven years. It purports to be a biography of the eponymous character. Its style is marked by digression, double entendre, and graphic devices. The first edition was printed by Ann Ward on Coney Street, York.

William Howard Gass was an American novelist, short story writer, essayist, critic, and philosophy professor. He wrote three novels, three collections of short stories, a collection of novellas, and seven volumes of essays, three of which won National Book Critics Circle Award prizes and one of which, A Temple of Texts (2006), won the Truman Capote Award for Literary Criticism. His 1995 novel The Tunnel received the American Book Award. His 2013 novel Middle C won the 2015 William Dean Howells Medal.

The genre of Menippean satire is a form of satire, usually in prose, that is characterized by attacking mental attitudes rather than specific individuals or entities. It has been broadly described as a mixture of allegory, picaresque narrative, and satirical commentary. Other features found in Menippean satire are different forms of parody and mythological burlesque, a critique of the myths inherited from traditional culture, a rhapsodic nature, a fragmented narrative, the combination of many different targets, and the rapid moving between styles and points of view.

Georg Christoph Lichtenberg was a German physicist, satirist, and Anglophile. As a scientist, he was the first to hold a professorship explicitly dedicated to experimental physics in Germany. He is remembered for his posthumously published notebooks, which he himself called Sudelbücher, a description modelled on the English bookkeeping term "waste books" or "scrapbooks", and for his discovery of tree-like electrical discharge patterns now called Lichtenberg figures.

Crepitus is an alleged Roman god of flatulence actually created by Christians and used in their literature frequently as a fascinating subject to them. It is unlikely that Crepitus was ever actually worshipped. The only ancient source for the claim that such a god was ever worshipped comes from Christian satire. The name Crepitus standing alone would be an inadequate and unlikely name for such a god in Latin. The god appears, however, in a number of important works of French literature.

Gillian Rosemary Rose was a British philosopher and writer. Rose held the chair of social and political thought at the University of Warwick until 1995. Rose began her teaching career at the University of Sussex. She worked in the fields of philosophy and sociology. Her writings include The Melancholy Science, Hegel Contra Sociology, Dialectic of Nihilism, Mourning Becomes the Law, and Paradiso, among others.

Experimental literature is a genre of literature that is generally "difficult to define with any sort of precision." It experiments with the conventions of literature, including boundaries of genres and styles; for example, it can be written in the form of prose narratives or poetry, but the text may be set on the page in differing configurations than that of normal prose paragraphs or in the classical stanza form of verse. It may also incorporate art or photography. Furthermore, while experimental literature was traditionally handwritten, the digital age has seen an exponential use of writing experimental works with word processors.

New York Review Books (NYRB) is the publishing division of The New York Review of Books. Its imprints are New York Review Books Classics, New York Review Books Collections, The New York Review Children's Collection, New York Review Comics, New York Review Books Poets, and NYRB Lit.

The Tunnel is a 1995 novel by the American author William H. Gass. The novel took 26 years to write and earned him the American Book Award of 1996, and was also a finalist for the PEN/Faulkner award.

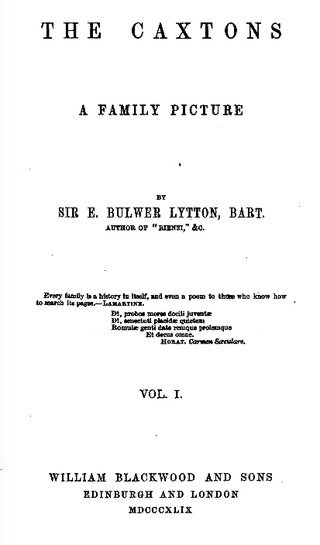

The Caxtons: A Family Picture is an 1849 Victorian novel by Edward Bulwer-Lytton that was popular in its time.

Damion Searls is an American writer and translator. He grew up in New York and studied at Harvard University and the University of California, Berkeley. He specializes in translating literary works from Western European languages such as German, Norwegian, French, and Dutch. Among the authors he has translated are Marcel Proust, Thomas Mann, Rainer Maria Rilke, Robert Walser, Ingeborg Bachmann, Thomas Bernhard, Kurt Schwitters, Peter Handke, Jon Fosse, Heike B. Görtemaker, and Nescio. He has received numerous grants and fellowships for his translations.

Boris Dralyuk is a Ukrainian-American writer, editor and translator. He obtained his high school degree from Fairfax High School and his PhD in Slavic Languages and Literatures from UCLA. He teaches in the English Department at the University of Tulsa. He has taught Russian literature at his alma mater and at the University of St Andrews, Scotland. From 2016 to 2022, he was executive editor and editor-in-chief of the Los Angeles Review of Books and he is the managing editor of Cardinal Points.