Prince Diponegoro, also known as Dipanegara, was a Javanese prince who opposed the Dutch colonial rule. The eldest son of the Yogyakarta Sultan Hamengkubuwono III, he played an important role in the Java War between 1825 and 1830. After his defeat and capture, he was exiled to Makassar, where he died, at 69 years old.

The Sultanate of Mataram was the last major independent Javanese kingdom on the island of Java before it was colonised by the Dutch. It was the dominant political force radiating from the interior of Central Java from the late 16th century until the beginning of the 18th century.

The Java War or Diponegoro War (ꦥꦼꦫꦁꦢꦶꦥꦤꦼꦒꦫ) was fought in central Java from 1825 to 1830, between the colonial Dutch Empire and native Javanese rebels. The war started as a rebellion led by Prince Diponegoro, a leading member of the Javanese aristocracy who had previously cooperated with the Dutch.

Magelang is one of six cities in Central Java Province of Indonesia that are administratively independent of the regencies in which they lie geographically. Each of these cities is governed by a mayor rather than a bupati. Magelang city covers an area of 18.54 km2 and has a population of 118,227 at the 2010 census and 121,526 at the 2020 census; the official estimate as at mid 2022 was 121,675. It is geographically located in the middle of the Magelang Regency, between Mount Merbabu and Mount Sumbing in the south of the province, and lies 43 km north of Yogyakarta, 15 km north of Mungkid and 75 km south of Semarang, the capital of Central Java.

Raden Saleh Sjarif Boestaman was a pioneering Indonesian Romantic painter of Arab-Javanese ethnicity. He was considered to be the first "modern" artist from Indonesia, and his paintings corresponded with nineteenth-century romanticism which was popular in Europe at the time. He also expressed his cultural roots and inventiveness in his work.

Sultan Anyakrakusuma is known as Sultan Agung was the third Sultan of Mataram in Central Java ruling from 1613 to 1645. He was a skilled soldier who conquered neighbouring states and expanded and consolidated his kingdom to its greatest territorial and military power.

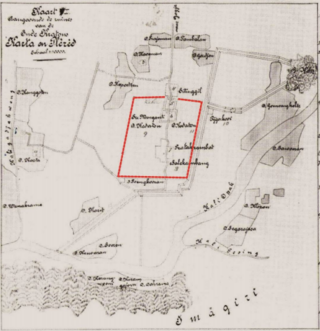

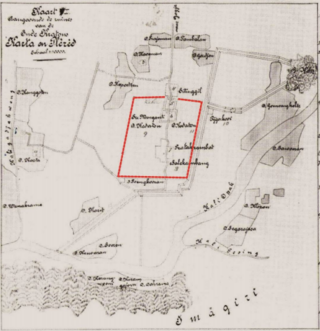

Plered was the location of the palace of Amangkurat I of Mataram (1645–1677). Amangkurat moved the capital there from the nearby Karta in 1647. During the Trunajaya rebellion, the capital was occupied and sacked by the rebels, and Amangkurat died during the retreat from the capital. His son and successor Amangkurat II later moved the capital to Kartasura. It was twice occupied by Diponegoro, during the Java War (1825–1830) between his forces and the Dutch. The Dutch assaulted the walled complex in June 1826, which was Diponegoro's first major defeat in the war.

Hamengkubuwono IV, also spelled Hamengkubuwana IV was the fourth sultan of Yogyakarta, Indonesia, reigning from 1814 to 1823.

Peter Carey is a British historian and author who specialises in the modern history of Indonesia, Java in particular, and has also written on East Timor and Myanmar. He was the Laithwaite fellow of Modern History at Trinity College, Oxford, from 1979 to 2008. His major early work concentrated on the history of Diponegoro, the British in Java, 1811–16 and the Java War (1825–30), on which he has published extensively. His biography of Diponegoro, The Power of Prophecy, appeared in 2007, and a succinct version, Destiny; The Life of Prince Diponegoro of Yogyakarta, 1785–1855, was published in 2014. He has conducted research in Lisbon and the United Kingdom amongst the exile East Timorese student community for an oral history of the Indonesian occupation of East Timor, 1975–99, part of which was published in the Cornell University journal Indonesia.

Sultanate of Banjar or Sultanate of Banjarmasin was a sultanate located in what is today the South Kalimantan province of Indonesia. For most of its history, its capital was at Banjarmasin.

Surakarta Sunanate is a Javanese monarchy centred in the city of Surakarta, in the province of Central Java, Indonesia.

November 1828 is a 1979 Indonesian historical drama directed by Teguh Karya. Production cost an estimated Rp 240 million, making it the most expensive Indonesian movie up to that point. It tells the story of a village struggling against the Dutch colonial military during the Java War, and touches on the themes of nationalism and cultural identity. The movie won 6 Citra Awards.

Raden Ajeng Kustiyah Wulaningsih Retno Edhi (1752–1838), better known as Nyi Ageng Serang, is a National Hero of Indonesia.

Friedrich Carl Albert Schreuel, also known as Frederik Karel Albert Schreuel and Jan Christian Aelbert Schreuel, was a Dutch-born painter.

Sasana Wiratama, also known as Museum Monumen Pangeran Diponegoro is a museum complex in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. The complex consists of a museum and a monument which commemorates the struggle of Prince Diponegoro, an 18th-century Javanese prince and a National Hero.

The Submission of Prince Dipo Negoro to General De Kock is an oil painting on canvas painted by Nicolaas Pieneman between 1830 and 1835. It depicts, from a victorious Dutch colonial perspective, the capture of Prince Diponegoro in 1830, which signaled the end of the Java War (1825–1830).

Pakubuwono I, uncle of Amangkurat III of Mataram was a combatant for the succession of the Mataram dynasty, both as a co-belligerent during the Trunajaya rebellion, and during the First Javanese War of Succession (1704–1707).

Paku Alam X is the Duke (Adipati) of Pakualaman, a small Javanese duchy in the Special Region of Yogyakarta, Indonesia. He succeeded as Paku Alam upon the death of the previous ruler, his father Paku Alam IX, who died on 21 November 2015. He was formally crowned with the Royal Javanese title of Kanjeng Gusti Pangeran Adipati Arya (KGPAA) Paku Alam X on 7 January 2016, and as stated in the National Constitution, on 25 May 2016, He was sworn and appointed as the hereditary Vice-Governor of Yogyakarta Special Region.

The Fall of Plered was the capture of the capital of the Mataram Sultanate by the rebel forces loyal to Trunajaya in late June 1677. The attack on Plered followed a series of rebel victory, notably in the Battle of Gegodog and the fall of most of Mataram's northern coast. The aged and sick King Amangkurat I and his sons offered an ineffective defense, and the rebel overran the capital on or around 28 June. The capital was plundered and its wealth taken to the rebel capital in Kediri. The loss of the capital led to the collapse of the Mataram government and the flight of the royal family. The king fled with his son the crown prince and a small retinue to Tegal and died there, passing the kingship to the crown prince, now titled Amangkurat II, without any army or treasury.

Stealing Raden Saleh is a 2022 heist action film directed by Angga Dwimas Sasongko and written by Sasongko and Husein M. Atmodjo. The film features an ensemble cast, consists of: Iqbaal Ramadhan, Angga Yunanda, Rachel Amanda, Umay Shahab, Aghniny Haque and Ari Irham. The film follows a group who plans a heist of The Arrest of Pangeran Diponegoro painting by Indonesian artist Raden Saleh.