The First Blast of the Trumpet Against the Monstruous Regiment of Women is a polemical work by the Scottish reformer John Knox, published in 1558. It attacks female monarchs, arguing that rule by women is contrary to the Bible.

The First Blast of the Trumpet Against the Monstruous Regiment of Women is a polemical work by the Scottish reformer John Knox, published in 1558. It attacks female monarchs, arguing that rule by women is contrary to the Bible.

The title employs certain words in spellings and senses that are now archaic. "Monstruous" (from Latin mōnstruōsus ) means "unnatural"; "regiment" (Late Latin regimentum or regimen) means "rule" or "government". The title is frequently found with the spelling slightly modernised, e.g. "monstrous regiment" or "monstrous regimen". It is clear however that the use of "regimen[t]" meant "rule" and should not be confused with "regiment" as in a section of an armed force.[ citation needed ]

The title appears in all capitals, except for the last four words; in accordance with 16th-century orthographical norms, capitalized "trumpet" and "monstruous" are written TRVMPET and MONSTRVOVS.[ citation needed ]

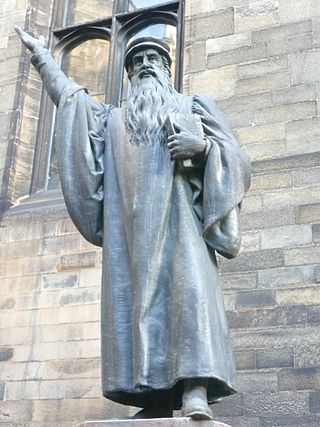

John Knox was a Scottish Protestant preacher and notary born in 1514 who was involved in some of the most contentious religious and political debates of the day. His preaching built Knox a congregation of followers who stayed loyal to him even after he had to flee to the continent. Knox believed that he was an authority on religious doctrine and frequently described himself as "watchman" [ citation needed ], drawing similarities between his life and that of Jeremiah, Ezekiel, Jehu and Daniel. He saw his duty as to "blow his master's trumpet". [1] [2] His views were not popular with the monarchy, though, so in 1554 Knox fled to mainland Europe.

At the time, both Scotland and England were governed by female leaders. While in Europe, Knox discussed this question of gynarchy with John Calvin and Heinrich Bullinger. Knox believed that gynarchy was contrary to the natural order of things, although Calvin and Bullinger believed it was acceptable for women to be rulers when the situation demanded.

While in Europe, Knox was summoned back to Scotland to a hearing to be tried for heresy. However Mary, Queen of Scots cancelled the hearing and in 1557, he was invited back to Scotland to resume his preaching. Upon his arrival at Dieppe he learned that the invitation had been cancelled. While waiting in Dieppe, the frustrated Knox anonymously wrote The First Blast of the Trumpet Against the Monstruous Regiment of Women. Unlike his other publications, Knox published the final version of The First Blast without consulting his exiled congregation and in 1558 he published it with the help of Jean Crespin. [3] [4] [5]

The bulk of The First Blast contained Knox's counterarguments to Calvin's viewpoints on gynarchy that they had discussed previously. While discussing gynarchy in general, Knox's target was mainly Queen Mary I.

Knox, a staunch Protestant Reformer, opposed the Catholic queens on religious grounds, and used them as examples to argue against female rule over men generally. Building on his premise that, according to Knox's understanding of the Bible, "God, by the order of his creation, has [deprived] woman of authority and dominion" and from history that "man has seen, proved, and pronounced just causes why it should be", he argued the following with regard to the specific role of women bearing authority:

For who can denie but it repugneth to nature, that the blind shal be appointed to leade and conduct such as do see? That the weake, the sicke, and impotent persones shall norishe and kepe the hole and strong, and finallie, that the foolishe, madde and phrenetike shal gouerne the discrete, and giue counsel to such as be sober of mind? And such be al women, compared vnto man in bearing of authoritie. For their sight in ciuile regiment, is but blindnes: their strength, weaknes: their counsel, foolishenes: and judgement, phrenesie, if it be rightlie considered.

Knox had three primary sections in The First Blast. First, that gynarchy was "'repugnant to Nature'; second, 'a contumlie to God'; and finally, 'the subversion of good order'". [6]

Knox believed that when a female ruled in society, it went against the natural order of things. He further went on to say that it was a virtue from God for women to serve men. [4] [6] Knox thought that civil obedience was a prerequisite for heaven and Mary was not in line with the civil obedience. [7] Although there were exceptions to this order, Knox believed that God was the only one who could make those exceptions. [6]

Knox appealed to the common belief that women were supposed to come after men because Eve came after (and from) Adam. [8] Furthermore, God's anger against Eve for taking the forbidden fruit had continued and all women were therefore punished by being subjected to men. [4] [6]

In his analysis of the Creation, Knox furthered his argument by stating that women were created in the image of God "only with respect to creatures, not with respect to man". Knox believed that men were a superior reflection of God and women were an inferior reflection. [6]

The First Blast contained four main counterarguments to John Calvin's arguments. First, Knox argued that while God had given authority to biblical female leaders, Deborah and Huldah, God had not given that authority to any female in the 16th century. Elaborating, Knox stated that the only similarity Queen Mary had with Deborah and Huldah was their gender. This was not sufficient to Knox. Furthermore, Deborah and Huldah did not claim the right to pass on their authority, but the queens did. [4]

One of Calvin's arguments was that gynarchy was acceptable since Moses had sanctioned the daughters of Zelophehad to receive an inheritance. Knox refuted this second point in The First Blast by pointing out that receiving an inheritance was not equivalent to gaining a civil office. The daughters were also required to marry within their tribe while Mary I had married Philip II of Spain. [4]

Calvin had told Knox that Mary I's rule was sanctioned because parliament and the general public had agreed to it. Knox countered this in The First Blast by stating that it did not matter if man agreed to the rule if God did not agree to it as well. [4]

The fourth point that Knox disagreed with Calvin on was accepting of gynarchy because it was a national custom. Knox conversely believed that Biblical authority and God's will made Calvin's argument invalid. [4]

The First Blast concluded by using a biblical metaphor to call the nobility to action and remove the queen from the throne. [3] In the Bible, Jehoiada, representing Knox, had instructed the rulers of the people to depose Athaliah, who represented Mary I. The Jews then executed the high priest of Baal, who represented Stephen Gardiner. [9] It was clear that Knox was calling for the removal of Queen Mary I. He may have even been demanding that she be executed. [10]

While many Christians in the 16th century believed it was their Christian duty to always follow their monarch, Knox believed it was worse for a Christian to follow a ruler that was evil. [9] He claimed that, if needed, a rebellion should take place to dethrone her. Many people in Scotland agreed with Knox that it was not natural for women to rule but they did not agree with his belief that the queens should be replaced. [11] Because of Knox's bold call to action, his contemporaries began to consider Knox as a revolutionary. [9]

Soon after publishing The First Blast, Knox continued to write fervently. Prior to August 1558, he wrote three items which supplemented The First Blast. He wrote to Mary of Guise to compel her to support Protestantism and to convince her to let him regain his right to preach. [4] He wrote to the nobility to convince them of their duty to rise up against the queen. And he wrote to the people of Scotland to convince them of the need for reform. [5]

Knox intended to write a Second Blast and a Third Blast, but after seeing how people responded to the First, neither ever became reality. [12]

His polemic against female rulers had negative consequences for him when Elizabeth I succeeded her half-sister Mary I as Queen of England; Elizabeth was a supporter of the Protestant cause, but took offence at Knox's words about female sovereigns. Her opposition to him personally became an obstacle to Knox's direct involvement with the Protestant cause in England after 1559. She blamed him and the city of Geneva for permitting The First Blast to be published. [3] Members of the Genevan congregation were searched, persecuted, and exiled. In 1558, the queen prohibited "importing of heretical and seditious books" into England. [12] After Knox revealed himself as the author of The First Blast, through a letter to the queen, he was refused entrance to England. [10] [4] Despite Knox's efforts to keep the blame for The First Blast on himself, his followers and other Protestants were punished. [12]

In a letter to Anna Locke on 6 April 1569, John Knox said, "To me it is written that my First Blast hath blown from me all my friends in England." Knox ended his letter, though, by saying that he stood by what he had said. [12] Through it all, Knox continued to see himself as a prophet and believe that he needed to still declare God's words. [4]

When Mary of Guise died in 1560, Knox wrote that Mary's unpleasant death and the deaths of her sons and husband were a divine judgement that would have been prevented if she had listened to the words in The First Blast. [10]

Knox was not the only person to write against gynarchy. Two other main publications were also written, one by Christopher Goodman and the other by Anthony Gilby. Unlike Knox whose argument hinged on the premise of gender, Gilby and Goodman's arguments were rooted in Mary I being a Catholic. [6] Others individuals including Jean Bodin, George Buchanan, Francois Hotman, and Montaigne also agreed with Knox, but their works were less known. [10]

Goodman relied on some of Knox's ideas in his publication "How Superior Powers Oght to be Obeyd". [3] He agreed that female rule was against God's will and natural law. After the publication of Goodman's and Knox works, their friendship increased. [3] But, while Goodman eventually rescinded his words about women rulers, Knox never did. [10]

On the other hand, many of Knox's contemporaries disagreed with his stance. In response to The First Blast, John Aylmer, an exiled English Protestant, wrote then published "An Harborowe for Faithful and Trewe Subjectes Agaynst the Late Blowne Blaste, Concerninge the Government of Wemen" on 26 April 1559. [13] [14] While Knox believed that the Bible held absolute authority on everything, including politics, Alymer disagreed. [6] He believed that the narratives in the Bible were not always God's way of explaining right and wrong but were sometimes historical expositions only. [6] Aylmer also argued that what Knox called "monstrous" was actually just "uncommon". This was portrayed by pointing out that although it was uncommon for a woman to give birth to twins, it was not monstrous.

Matthew Parker, John Foxe, Laurence Humphrey, Edmund Spenser, and John Lesley also opposed Knox's views in The First Blast and John Calvin and Theodore Beza banned it from being sold. [10]

Despite his polemic against gynarchy in The First Blast, modern scholars of Knox have defended him against accusations of misogyny.

As Richard Lee Greaves, a professor of History at Florida State University, said, "John Knox has gained a certain degree of notoriety in the popular mind as an antifeminist because of his attack on female sovereigns in The First Blast of the Trumpet against the Monstrous Regiment of Women (1558). Yet his attack was by no means original, for similar views were propounded in the sixteenth century by diverse writers." [10]

Susan M. Felch, director of Calvin Center for Christian Scholarship and a Professor of English, believed that Knox was not misogynistic but just passionate about maintaining the natural order of things. Felch further stated that while Knox was writing The First Blast he was writing letters to women which were "remarkably free of gendered rhetoric". Knox addressed his female friends as partners in the fight against sin. Accompanied with expressions of non-romantic love, Knox gave spiritual advice to them but also believed that women could make their own spiritual decisions and encouraged them to do so. Felch believed that Knox did not think of Mary I as a lesser being, but believed that her decision to take the throne was sinful. [13]

Richard G. Kyle also agreed that Knox could not have been misogynistic because, besides The First Blast, Knox's writing did not deride or ridicule women. [9]

A. Daniel Frankforter, a history professor at PennState, pointed to times when Knox complimented women as evidence for Knox's non-misogynistic beliefs. He cited, for example, the time when Knox told his mother-in-law that she was a mirror to his soul. [15] Frankforter also believed that while Knox's rhetoric appears "virulent" and "misogynistic", it was likely no worse than everyone else in his time. [16]

Rosalind Marshall, a historian and Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature, believed that the tone in The First Blast was defensive not aggressive. She further claimed that The First Blast was not meant as an accusation against all women but just the female monarchs. Additionally, Marshall believed that Knox was in a "religious fervour" when he wrote The First Blast and would not have normally written such cruel things when he held women in such high esteem. [12]

Jane E. Dawson, a professor of Reformation History at the University of Edinburgh, pointed out that Knox did not always have antagonism toward Mary Queen of Scots since they previously worked well together. [3] She also agreed that the high majority of Knox's writings were uplifting instead of condemning. She contests that Knox lashed out at Mary I because he felt isolated and persecuted. [3]

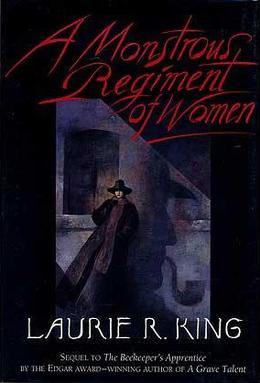

Around the 20th century, the work's title became a popular ironic cliché in feminist literature and art. Examples include the novels Regiment of Women (1917), A Monstrous Regiment of Women (1995), and Monstrous Regiment (2003), as well as the feminist British theatre troupe, the Monstrous Regiment Theatre Company.

John Knox was a Scottish minister, Reformed theologian, and writer who was a leader of the country's Reformation. He was the founder of the Presbyterian Church of Scotland.

Year 1558 (MDLVIII) was a common year starting on Saturday of the Julian calendar.

Matriarchy is a social system in which positions of dominance and authority are primarily held by women. In a broader sense it can also extend to moral authority, social privilege, and control of property. While those definitions apply in general English, definitions specific to anthropology and feminism differ in some respects. Most anthropologists hold that there are no known societies that are unambiguously matriarchal.

John Aylmer was an English bishop, constitutionalist and a Greek scholar.

Events from the year 1558 in literature.

Monstrous Regiment may refer to:

(Divine) Accommodation is the theological principle that God, while being in his nature unknowable and unreachable, has nevertheless communicated with humanity in a way that humans can understand and to which they can respond, pre-eminently by the incarnation of Christ and similarly, for example, in the Bible.

The Marian exiles were English Protestants who fled to continental Europe during the 1553–1558 reign of the Catholic monarchs Queen Mary I and King Philip. They settled chiefly in Protestant countries such as the Netherlands, Switzerland and Germany, and also in France, Italy and Poland.

The Scots Confession is a Confession of Faith written in 1560 by six leaders of the Protestant Reformation in Scotland. The text of the Confession was the first subordinate standard for the Protestant church in Scotland. Along with the Book of Discipline and the Book of Common Order, this is considered to be a formational document for the Church of Scotland during the time.

The status of Women in the Protestant Reformation was deeply influenced by Bible study, as the Reformation promoted literacy and Bible study in order to study God's will in what a society should look like. This influenced women's lives in both positive and negative ways, depending on what scripture and passages of the Bible were studied and promoted. The ideal of Bible study for commoners improved women's literacy and education, and many women became known for their interest and involvement in public debate during the Reformation. In parallel, however, their voices were often suppressed because of the edict of the Bible that women were to be silent. The abolition of the female convents resulted in the role of wife and mother becoming the only remaining ideal for a woman.

A Monstrous Regiment of Women is the second book in the Mary Russell series of mystery novels by Laurie R. King.

Christian feminism is a school of Christian theology which uses the viewpoint of a Christian to promote and understand morally, socially, and spiritually the equality of men and women. Christian theologians argue that contributions by women and acknowledging women's value are necessary for a complete understanding of Christianity. Christian feminists are driven by the belief that God does not discriminate on the basis of biologically-determined characteristics such as sex and race, but created all humans to exist in harmony and equality regardless of those factors. On the other hand, Christian egalitarianism is used for those advocating gender equality and equity among Christians but do not wish to associate themselves with the feminist movement.

The Scottish Reformation was the process whereby Scotland broke away from the Catholic Church, and established the Protestant Church of Scotland. It forms part of the wider European 16th century Protestant Reformation.

Christopher Goodman BD (1520–1603) was an English reforming clergyman and writer. He was a Marian exile, who left England to escape persecution during the counter-reformation in the reign of Queen Mary I of England. He was the author of a work on limits to obedience to rulers, and a contributor to the Geneva Bible. He was a friend of John Knox, and on Mary's death went to Scotland, later returning to England where he failed to conform.

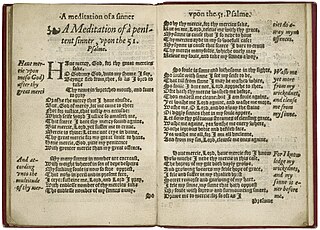

Anne Locke was an English poet, translator and Calvinist religious figure. She has been called the first English author to publish a sonnet sequence, A Meditation of a Penitent Sinner (1560), although authorship of that work has arguably been attributed to Thomas Norton.

Eric Patrick McCormack was a Scottish-born Canadian author. He was known for works blending absurdism, existentialism, crime fiction, gothic horror and the search for identity and personal meaning in works such as Inspecting the Vaults (1987), The Paradise Motel (1989), The Mysterium (1992), First Blast of the Trumpet Against the Monstrous Regiment of Women (1997) and The Dutch Wife (2002).

The Confession of Faith, popularly known as the Belgic Confession, is a doctrinal standard document to which many Reformed churches subscribe. The Confession forms part of the Three Forms of Unity of the Reformed Church, which are also the official subordinate standards of the Dutch Reformed Church. The confession's chief author was Guido de Brès, a preacher of the Reformed churches of the Netherlands, who died a martyr to the faith in 1567, during the Dutch Reformation. De Brès first wrote the Belgic Confession in 1559.

Monstrous Regiment Theatre Company is a British feminist theatre company established in 1975. Monstrous Regiment went on to produce and perform 30 major shows, in which the main focus was on women's lives and experiences. Performer-led and collectively organised, its work figures prominently in studies of feminist theatre in Britain during the 1970s and 1980s. No productions have been mounted since 1993, when financial support from the Arts Council of Great Britain was discontinued.

Church music during the Reformation developed during the Protestant Reformation in two schools of thought, the regulative and normative principles of worship, based on reformers John Calvin and Martin Luther. They derived their concepts in response to the Catholic church music, which they found distracting and too ornate. Both principles also pursued use of the native tongue, either alongside or in place of liturgical Latin.

Monstrous Regiment Publishing is an independent micropublisher based in Edinburgh. The company was set up by Ellen Desmond and Lauren Nickodemus, two graduates of Edinburgh Napier University. It publishes texts that focus on "intersectional feminism, sexuality and gender."