Theodore Roosevelt Jr., often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26th president of the United States from 1901 to 1909. He previously served as the 25th vice president under President William McKinley from March to September 1901 and as the 33rd governor of New York from 1899 to 1900. Assuming the presidency after McKinley's assassination, Roosevelt emerged as a leader of the Republican Party and became a driving force for anti-trust and Progressive policies.

The Russo-Japanese War was fought between the Empire of Japan and the Russian Empire during 1904 and 1905 over rival imperial ambitions in Manchuria and the Korean Empire. The major theatres of military operations were in Liaodong Peninsula and Mukden in Southern Manchuria, and the Yellow Sea and the Sea of Japan.

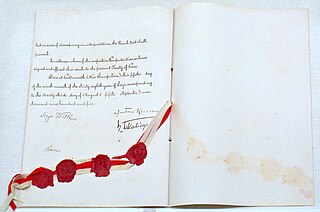

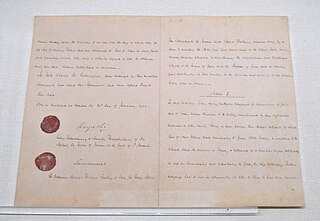

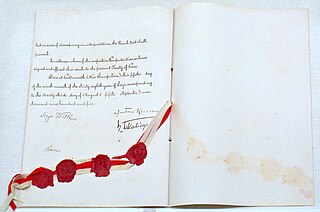

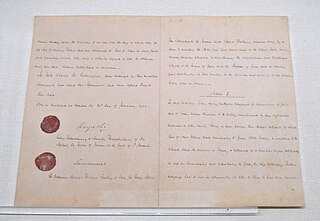

The Treaty of Portsmouth is a treaty that formally ended the 1904–1905 Russo-Japanese War. It was signed on September 5, 1905, after negotiations from August 6 to August 30, at the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard in Kittery, Maine, United States. U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt was instrumental in the negotiations and won the Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts.

Big stick ideology, big stick diplomacy, big stick philosophy, or big stick policy refers to an aphorism often said by the 26th president of the United States, Theodore Roosevelt; "speak softly and carry a big stick; you will go far". The American press during his time, as well as many modern historians today, used the term "big stick" to describe the foreign policy positions during his administration. Roosevelt described his style of foreign policy as "the exercise of intelligent forethought and of decisive action sufficiently far in advance of any likely crisis". As practiced by Roosevelt, big stick diplomacy had five components. First, it was essential to possess serious military capability that would force the adversary to pay close attention. At the time that meant a world-class navy; Roosevelt never had a large army at his disposal. The other qualities were to act justly toward other nations, never to bluff, to strike only when prepared to strike hard, and to be willing to allow the adversary to save face in defeat.

The Gentlemen's Agreement of 1907 was an informal agreement between the United States of America and the Empire of Japan whereby Japan would not allow further emigration to the United States and the United States would not impose restrictions on Japanese immigrants already present in the country. The goal was to reduce tensions between the two Pacific nations such as those that followed the Pacific Coast race riots of 1907 and the segregation of Japanese students in public schools. The agreement was not a treaty and so was not voted on by the United States Congress. It was superseded by the Immigration Act of 1924.

The Open Door Policy is the United States diplomatic policy established in the late 19th and early 20th century that called for a system of equal trade and investment and to guarantee the territorial integrity of Qing China. The policy was enunciated in U.S. Secretary of State John Hay's Open Door Note, dated September 6, 1899, and circulated to the major European powers. In order to prevent the "carving of China like a melon," as they were doing in Africa, the Note asked the powers to keep China open to trade with all countries on an equal basis and called upon all powers, within their spheres of influence to refrain from interfering with any treaty port or any vested interest, to permit Chinese authorities to collect tariffs on an equal basis, and to show no favors to their own nationals in the matter of harbor dues or railroad charges. The policy was accepted only grudgingly, if at all, by the major powers, and it had no legal standing or enforcement mechanism. In July 1900, as the powers contemplated intervention to put down the violently anti-foreign Boxer uprising, Hay circulated a Second Open Door Note affirming the principles. Over the next decades, American policy-makers and national figures continued to refer to the Open Door Policy as a basic doctrine, and Chinese diplomats appealed to it as they sought American support, but critics pointed out that the policy had little practical effect.

The first Anglo-Japanese Alliance was an alliance between Britain and Japan. It was in operation from 1902 to 1922. The original British goal was to prevent Russia from expanding in Manchuria while also preserving the territorial integrity of China and Korea. For the British, it marked the end of a period of "splendid isolation" while allowing for greater focus on protecting India and competing in the Anglo-German naval arms race. The alliance was part of a larger British strategy to reduce imperial overcommitment and recall the Royal Navy to defend Britain. The Japanese, on the other hand, gained international prestige from the alliance and used it as a foundation for their diplomacy for two decades. In 1905, the treaty was redefined in favor of Japan concerning Korea. It was renewed in 1911 for another ten years and replaced by the Four Power Treaty in 1922.

The Taft–Katsura Agreement, also known as the Taft-Katsura Memorandum, was a 1905 discussion between senior leaders of Japan and the United States regarding the positions of the two nations in greater East Asian affairs, especially regarding the status of Korea and the Philippines in the aftermath of Japan's victory during the Russo-Japanese War. The memorandum was not classified as a secret, but no scholar noticed it in the archives until 1924.

James Bradley is an American author from Antigo, Wisconsin, specializing in historical nonfiction chronicling the Pacific theatre of World War II. His father, John Bradley, was involved in the first raising of the American flag on Mount Suribachi during the Battle of Iwo Jima in 1945.

The Root–Takahira Agreementwas a major 1908 agreement between the United States and the Empire of Japan that was negotiated between United States Secretary of State Elihu Root and Japanese Ambassador to the United States Takahira Kogorō. It was a statement of longstanding policies held by both nations, much like the Taft–Katsura Agreement of 1905. Both agreements acknowledged key overseas territories controlled by each nation. Neither agreement was a treaty and no Senate approval was needed.

International relations between Japan and the United States began in the late 18th and early 19th century with the diplomatic but force-backed missions of U.S. ship captains James Glynn and Matthew C. Perry to the Tokugawa shogunate. Following the Meiji Restoration, the countries maintained relatively cordial relations. Potential disputes were resolved. Japan acknowledged American control of Hawaii and the Philippines, and the United States reciprocated regarding Korea. Disagreements about Japanese immigration to the U.S. were resolved in 1907. The two were allies against Germany in World War I.

The presidency of Theodore Roosevelt started on September 14, 1901, when Theodore Roosevelt became the 26th president of the United States upon the assassination of President William McKinley, and ended on March 4, 1909. Roosevelt had been the vice president for only 194 days when he succeeded to the presidency. A Republican, he ran for and won by a landslide a four-year term in 1904. He was succeeded by his protégé and chosen successor, William Howard Taft.

Wilsonianism, or Wilsonian idealism, is a certain type of foreign policy advice. The term comes from the ideas and proposals of President Woodrow Wilson. He issued his famous Fourteen Points in January 1918 as a basis for ending World War I and promoting world peace. He was a leading advocate of the League of Nations to enable the international community to avoid wars and end hostile aggression. Wilsonianism is a form of liberal internationalism.

History of United States foreign policy is a brief overview of major trends regarding the foreign policy of the United States from the American Revolution to the present. The major themes are becoming an "Empire of Liberty", promoting democracy, expanding across the continent, supporting liberal internationalism, contesting World Wars and the Cold War, fighting international terrorism, developing the Third World, and building a strong world economy with low tariffs.

William Franklin Sands was a United States diplomat most known for his service in Korea on the eve of Japan's colonization of that country.

The history of Japanese foreign relations deals with the international relations in terms of diplomacy, economics and political affairs from about 1850 to 2000. The kingdom was virtually isolated before the 1850s, with limited contacts through Dutch traders. The Meiji Restoration was a political revolution that installed a new leadership that was eager to borrow Western technology and organization. The government in Tokyo carefully monitored and controlled outside interactions. Japanese delegations to Europe brought back European standards which were widely imposed across the government and the economy. Trade flourished, as Japan rapidly industrialized.

The foreign policy of the United States was controlled personally by Franklin D. Roosevelt during his first and second and third and fourth terms as the president of the United States from 1933 to 1945. He depended heavily on Henry Morgenthau Jr., Sumner Welles, and Harry Hopkins. Meanwhile, Secretary of State Cordell Hull handled routine matters. Roosevelt was an internationalist, while powerful members of Congress favored more isolationist solutions in order to keep the U.S. out of European wars. There was considerable tension before the Attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 converted the isolationists or made them irrelevant. The US began aid to the Soviet Union after Germany invaded it in June 1941. After the US declared war in December 1941, key decisions were made at the highest level by Roosevelt, Britain's Winston Churchill and the Soviet Union's Joseph Stalin, along with their top aides. After 1938 Washington's policy was to help China in its war against Japan, including cutting off money and oil to Japan. While isolationism was powerful regarding Europe, American public and elite opinion strongly opposed Japan.

The history of U.S. foreign policy from 1897 to 1913 concerns the foreign policy of the United States during the Presidency of William McKinley, Presidency of Theodore Roosevelt, and Presidency of William Howard Taft. This period followed History of U.S. foreign policy, 1861–1897 and began with the inauguration of McKinley in 1897. It ends with Woodrow Wilson in 1913, and the 1914 outbreak of World War I, which marked the start of new era in U.S. foreign policy.

East Asia–United States relations covers American relations with the region as a whole, as well as summaries of relations with China, Japan, Korea, Taiwan and smaller places. It includes diplomatic, military, economic, social and cultural ties. The emphasis is on historical developments.

The foreign policy of the Theodore Roosevelt administration covers American foreign policy from 1901 to 1909, with attention to the main diplomatic and military issues, as well as topics such as immigration restriction and trade policy. For the administration as a whole see Presidency of Theodore Roosevelt. In foreign policy, he focused on Central America where he began construction of the Panama Canal. He modernized the U.S. Army and expanded the Navy. He sent the Great White Fleet on a world tour to project American naval power. Roosevelt was determined to continue the expansion of U.S. influence begun under President William McKinley (1897–1901). Roosevelt presided over a rapprochement with the Great Britain. He promulgated the Roosevelt Corollary, which held that the United States would intervene in the finances of unstable Caribbean and Central American countries in order to forestall direct European intervention. Partly as a result of the Roosevelt Corollary, the United States would engage in a series of interventions in Latin America, known as the Banana Wars. After Colombia rejected a treaty granting the U.S. a lease across the isthmus of Panama, Roosevelt supported the secession of Panama. He subsequently signed a treaty with Panama which established the Panama Canal Zone. The Panama Canal was completed in 1914, greatly reducing transport time between the Atlantic Ocean and the Pacific Ocean. Roosevelt's well-publicized actions were widely applauded.