Justice, in its broadest sense, is the concept that individuals are to be treated in a manner that is equitable and fair.

Social justice is justice in relation to a fair balance in the distribution of wealth, opportunities, and privileges within a society where individuals' rights are recognized and protected. In Western and Asian cultures, the concept of social justice has often referred to the process of ensuring that individuals fulfill their societal roles and receive their due from society. In the current movements for social justice, the emphasis has been on the breaking of barriers for social mobility, the creation of safety nets, and economic justice. Social justice assigns rights and duties in the institutions of society, which enables people to receive the basic benefits and burdens of cooperation. The relevant institutions often include taxation, social insurance, public health, public school, public services, labor law and regulation of markets, to ensure distribution of wealth, and equal opportunity.

John Bordley Rawls was an American moral, legal and political philosopher in the modern liberal tradition. Rawls has been described as one of the most influential political philosophers of the 20th century.

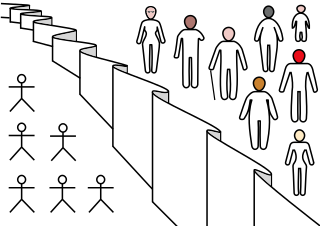

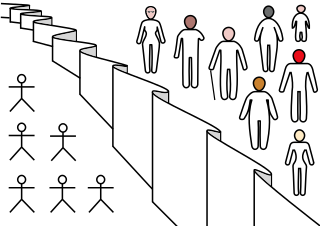

Distributive justice concerns the socially just allocation of resources, goods, opportunity in a society. It is concerned with how to allocate resources fairly among members of a society, taking into account factors such as wealth, income, and social status. Often contrasted with just process and formal equal opportunity, distributive justice concentrates on outcomes. This subject has been given considerable attention in philosophy and the social sciences. Theorists have developed widely different conceptions of distributive justice. These have contributed to debates around the arrangement of social, political and economic institutions to promote the just distribution of benefits and burdens within a society. Most contemporary theories of distributive justice rest on the precondition of material scarcity. From that precondition arises the need for principles to resolve competing interest and claims concerning a just or at least morally preferable distribution of scarce resources.

The original position (OP), often referred to as the veil of ignorance, is a thought experiment used for reasoning about the principles that should structure a society based on mutual dependence. The phrases original position and veil of ignorance were coined by the American philosopher John Rawls, but the thought experiment itself was developed by William Vickrey and John Harsanyi in earlier writings.

A Theory of Justice is a 1971 work of political philosophy and ethics by the philosopher John Rawls (1921–2002) in which the author attempts to provide a moral theory alternative to utilitarianism and that addresses the problem of distributive justice . The theory uses an updated form of Kantian philosophy and a variant form of conventional social contract theory. Rawls's theory of justice is fully a political theory of justice as opposed to other forms of justice discussed in other disciplines and contexts.

In ethics, political philosophy, social contract theory, religion, and international law, the term state of nature describes the hypothetical way of life that existed before humans organised themselves into societies or civilizations. Philosophers of the state of nature theory propose that there was a historical period before societies existed, and seek answers to the questions: "What was life like before civil society?", "How did government emerge from such a primitive start?", and "What are the hypothetical reasons for entering a state of society by establishing a nation-state?".

Public reason requires that the moral or political rules that regulate our common life be, in some sense, justifiable or acceptable to all those persons over whom the rules purport to have authority. It is an idea with roots in the work of Thomas Hobbes, Immanuel Kant, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and has become increasingly influential in contemporary moral and political philosophy as a result of its development in the work of John Rawls, Jürgen Habermas, and Gerald Gaus, among others.

Ronald Myles Dworkin was an American legal philosopher, jurist, and scholar of United States constitutional law. At the time of his death, he was Frank Henry Sommer Professor of Law and Philosophy at New York University and Professor of Jurisprudence at University College London. Dworkin had taught previously at Yale Law School and the University of Oxford, where he was the Professor of Jurisprudence, successor to philosopher H. L. A. Hart.

In philosophy, economics, and political science, the common good is either what is shared and beneficial for all or most members of a given community, or alternatively, what is achieved by citizenship, collective action, and active participation in the realm of politics and public service. The concept of the common good differs significantly among philosophical doctrines. Early conceptions of the common good were set out by Ancient Greek philosophers, including Aristotle and Plato. One understanding of the common good rooted in Aristotle's philosophy remains in common usage today, referring to what one contemporary scholar calls the "good proper to, and attainable only by, the community, yet individually shared by its members."

Toleration is when one allows, permits, or accepts an action, idea, object, or person that one dislikes or disagrees with.

Political Liberalism is a 1993 book by the American philosopher John Rawls, an update to his earlier A Theory of Justice (1971). In it, he attempts to show that his theory of justice is not a "comprehensive conception of the good" but is instead compatible with a liberal conception of the role of justice, namely, that government should be neutral between competing conceptions of the good. Rawls tries to show that his two principles of justice, properly understood, form a "theory of the right" which would be supported by all reasonable individuals, even under conditions of reasonable pluralism. The mechanism by which he demonstrates this is called "overlapping consensus". Here he also develops his idea of public reason.

Overlapping consensus is a term coined by John Rawls in A Theory of Justice and developed in Political Liberalism. The term overlapping consensus refers to how supporters of different comprehensive normative doctrines—that entail apparently inconsistent conceptions of justice—can agree on particular principles of justice that underwrite a political community's basic social institutions. Comprehensive doctrines can include systems of religion, political ideology, or morality.

Global justice is an issue in political philosophy arising from the concern about unfairness. It is sometimes understood as a form of internationalism.

"Instrumental" and "value rationality" are terms scholars use to identify two ways individuals act in order to optimize their behavior. Instrumental rationality recognizes means that "work" efficiently to achieve ends. Value rationality recognizes ends that are "right," legitimate in themselves.

Justice as Fairness: A Restatement is a 2001 book of political philosophy by the philosopher John Rawls, published as a restatement of his 1971 classic A Theory of Justice (1971). The restatement was made largely in response to the significant number of critiques and essays written about Rawls's 1971 book on this subject. The released book was edited by Erin Kelly while Rawls was in declining health during his final years.

Perfectionist liberalism has been defined by Charles Larmore (1987) as the "family of views that base political principles on 'ideals claiming to shape our overall conception of the good life, and not just our role as citizens.'" Joseph Raz popularised those ideas. Other important contemporary theorists of liberal perfectionism are George Sher and Steven Wall. One can also find liberal perfectionist strands of thought in the writings of early liberals like John Stuart Mill and T. H. Green.

Knowledge and Politics is a 1975 book by philosopher and politician Roberto Mangabeira Unger. In it, Unger criticizes classical liberal doctrine, which originated with European social theorists in the mid-17th century and continues to exercise a tight grip over contemporary thought, as an untenable system of ideas, resulting in contradictions in solving the problems that liberal doctrine itself identifies as fundamental to human experience. Liberal doctrine, according to Unger, is an ideological prison-house that condemns people living under its spell to lives of resignation and disintegration. In its place, Unger proposes an alternative to liberal doctrine that he calls the "theory of organic groups," elements of which he finds emergent in partial form in the welfare-corporate state and the socialist state. The theory of organic groups, Unger contends, offers a way to overcome the divisions in human experience that make liberalism fatally flawed. The theory of organic groups shows how to revise society so that all people can live in a way that is more hospitable to the flourishing of human nature as it is developing in history, particularly in allowing people to integrate their private and social natures, achieving a wholeness in life that has previously been limited to the experience of a small elite of geniuses and visionaries.

In political philosophy, an ideal theory is a theory which specifies the optimal societal structure based on idealised assumptions and normative theory. It stems from the assumption that citizens are fully compliant to a state which enjoys favorable social conditions, which makes it unrealistic in character. Ideal theories do not offer solutions to real world problems, instead the aim of ideal theory is to provide a guide for improvements based on what society should normatively appear to be. Another interpretation of ideal theories is that they are end-state theories.