Thomas Ernest Bennett "Tibby" Clarke, OBE was a film screenwriter who wrote several of the Ealing Studios comedies.

Johnny Speight was an English television scriptwriter of many classic British sitcoms.

The Ealing comedies is an informal name for a series of comedy films produced by the London-based Ealing Studios during a ten-year period from 1947 to 1957. Often considered to reflect Britain's post-war spirit, the most celebrated films in the sequence include Kind Hearts and Coronets (1949), Whisky Galore! (1949), The Lavender Hill Mob (1951), The Man in the White Suit (1951) and The Ladykillers (1955). Hue and Cry (1947) is generally considered to be the earliest of the cycle, and Barnacle Bill (1957) the last, although some sources list Davy (1958) as the final Ealing comedy. Many of the Ealing comedies are ranked among the greatest British films, and they also received international acclaim.

Sir Michael Elias Balcon was an English film producer known for his leadership of Ealing Studios in West London from 1938 to 1955. Under his direction, the studio became one of the most important British film studios of the day. In an industry short of Hollywood-style moguls, Balcon emerged as a key figure, and an obdurately British one too, in his benevolent, somewhat headmasterly approach to the running of a creative organization. He is known for his leadership, and his guidance of young Alfred Hitchcock.

Charles Ainslie Crichton was an English film director and editor.

John Gregson, born as Harold Thomas Gregson, was an English actor of stage, television and film, with 40 credited film roles. He was best known for his crime drama and comedy roles.

Hue and Cry is a 1947 British film directed by Charles Crichton and starring Alastair Sim, Harry Fowler and Joan Dowling.

James Robertson Justice was an English actor. He is best remembered for portraying pompous authority figures in comedies including each of the seven films in the Doctor series. He also co-starred with Gregory Peck in several adventure movies, notably The Guns of Navarone. Born in south-east London to a Scottish father, he became prominent in Scottish public life, helping to launch Scottish Television (STV) and serving as Rector of the University of Edinburgh.

Dayle Lymoine Robertson was an American actor best known for his starring roles on television. He played the roving investigator Jim Hardie in the television series Tales of Wells Fargo and railroad owner Ben Calhoun in Iron Horse. He often was presented as a deceptively thoughtful but modest Western hero. From 1968 to 1970, Robertson was the fourth and final host of the anthology series Death Valley Days. Described by Time magazine in 1959 as "probably the best horseman on television", for most of his career, Robertson played in western films and television shows—well over 60 titles in all.

Seth Holt was a Palestinian-born British film director, producer and editor. His films are characterized by their tense atmosphere and suspense, as well as their striking visual style. In the 1960s, Movie magazine championed Holt as one of the finest talents working in the British film industry, although his output was notably sparse.

Arthur Haynes was an English comedian and star of The Arthur Haynes Show, a comedy sketch series produced by ATV from 1956 until his death from a heart attack in 1966. Haynes also appeared on radio and in films.

Basil Dearden was an English film director.

Wylie Watson was a British actor. Among his best-known roles were those of "Mr Memory", an amazing man who commits "50 new facts to his memory every day" in Alfred Hitchcock's film The 39 Steps (1935), and wily storekeeper Joseph Macroon in the Ealing comedy Whisky Galore! (1949). He emigrated to Australia in 1952, and made his final film appearance there in The Sundowners (1960).

Charles Herbert Frend was an English film director and editor, best known for his films produced at Ealing Studios. He began directing in the early 1940s and is known for such films as Scott of the Antarctic (1948) and The Cruel Sea (1953).

Father Came Too! is a 1964 British comedy film directed by Peter Graham Scott and starring James Robertson Justice, Leslie Phillips and Stanley Baxter. It is a loose sequel to The Fast Lady (1962).

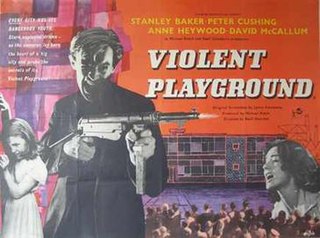

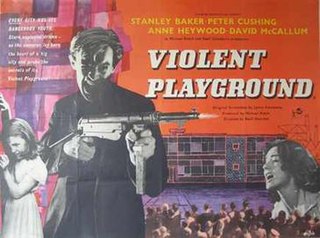

Violent Playground is a black and white 1958 British film directed by Basil Dearden and starring Stanley Baker, Peter Cushing, and David McCallum. The film, which deals with the genre of juvenile delinquent, has an explicit social agenda. It owes much to U.S. films of a similar genre.

Cheer Boys Cheer is a 1939 British comedy film directed by Walter Forde and starring Nova Pilbeam, Edmund Gwenn, Jimmy O'Dea, Graham Moffatt, Moore Marriott and Peter Coke.

Saloon Bar is a 1940 British comedy thriller film directed by Walter Forde and starring Gordon Harker, Elizabeth Allan and Mervyn Johns. It was made by Ealing Studios and its style has led to comparisons with the later Ealing Comedies, unlike other wartime Ealing films which are different in tone. It is based on the 1939 play of the same name by Frank Harvey in which Harker had also starred. An amateur detective tries to clear an innocent man of a crime before the date of his execution.

Sailors Three is a 1940 British war comedy film directed by Walter Forde and starring Tommy Trinder, Claude Hulbert and Carla Lehmann. This was cockney music hall comedian Trinder's debut for Ealing, the studio with which he was to become most closely associated. It concerns three British sailors who accidentally find themselves aboard a German ship during the Second World War.

Our New Errand Boy is a 1905 British short silent comedy film, directed by James Williamson, about a new errand boy, engaged by a grocer who soon regrets the appointment. This "relatively unambitious" chase comedy, according to Michael Brooke of BFI Screenonline, "is one of a number of Williamson films featuring a mischievous child, played by the director's son Tom". "Although essentially a series of sketches", this film, according to David Fisher, "demonstrates the extent to which Williamson had developed film technique For a start, the film has a title frame, which includes the logo of the Williamson Cinematograph Company", and, "the chase section anticipates the American comedies of the next decade".