The Federal Trade Commission Act of 1914 is a United States federal law which established the Federal Trade Commission. The Act was signed into law by US President Woodrow Wilson in 1914 and outlaws unfair methods of competition and unfair acts or practices that affect commerce.

The Wheeler–Lea Act of 1938 is a United States federal law that amended Section 5 of the Federal Trade Commission Act to proscribe "unfair or deceptive acts or practices" as well as "unfair methods of competition." It provided civil penalties for violations of Section 5 orders. It also added a clause to Section 5 that stated "unfair or deceptive acts or practices in commerce are hereby declared unlawful" to the Section 5 prohibition of unfair methods of competition in order to protect consumers as well as competition.

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) is an independent agency of the United States government whose principal mission is the enforcement of civil (non-criminal) antitrust law and the promotion of consumer protection. The FTC shares jurisdiction over federal civil antitrust law enforcement with the Department of Justice Antitrust Division. The agency is headquartered in the Federal Trade Commission Building in Washington, DC.

Greenwashing, also called "green sheen", is a form of advertising or marketing spin in which green PR and green marketing are deceptively used to persuade the public that an organization's products, aims and policies are environmentally friendly. Companies that intentionally take up greenwashing communication strategies often do so in order to distance themselves from their own environmental lapses or those of their suppliers.

The Controlling the Assault of Non-Solicited Pornography And Marketing (CAN-SPAM) Act of 2003 is a law passed in 2003 establishing the United States' first national standards for the sending of commercial e-mail. The law requires the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to enforce its provisions. Introduced by Republican Conrad Burns, the act passed both the House and Senate during the 108th United States Congress and was signed into law by President George W. Bush in December 2003.

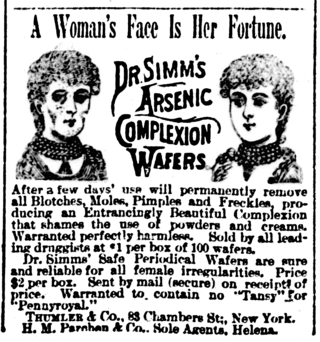

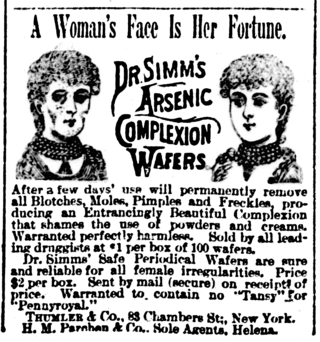

False advertising is defined as the act of publishing, transmitting, or otherwise publicly circulating an advertisement containing a false claim, or statement, made intentionally to promote the sale of property, goods, or services. A false advertisement can be classified as deceptive if the advertiser deliberately misleads the consumer, rather than making an unintentional mistake. A number of governments use regulations to limit false advertising.

Direct Revenue was a New York City company which distributed software that displays pop-up advertising on web browsers. It was founded in 2002 and funded by Insight Venture Partners, known for creating adware programs. Direct Revenue included Soho Digital and Soho Digital International. Its competitors included Claria, When-U, Ask.com and products created by eXact Advertising. The company's major clients included Priceline, Travelocity, American Express, and Ford Motors. Direct Revenue's largest distributors were Advertising.com and 247 Media. In October 2007, Direct Revenue closed its doors.

BlueHippo Funding, LLC was an installment credit company operating in the USA founded by Joseph Rensin that claimed to offer personal computers, flat-screen televisions and other high-tech items for sale to customers with poor credit. In an article published November 25, 2009 titled BlueHippo files for bankruptcy: Company blames its bank; was accused of violating settlement with FTC, Eileen Ambrose reported that the company "was forced to file for protection under Chapter 11." On Wednesday December 9, 2009, the company filed for Chapter 7 bankruptcy after having its funds frozen by their payment processor. A petition to a Delaware bankruptcy judge to release the funds was denied. The company's advertised toll-free phone number and website are no longer functioning.

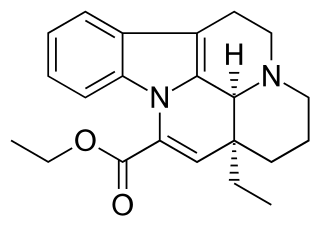

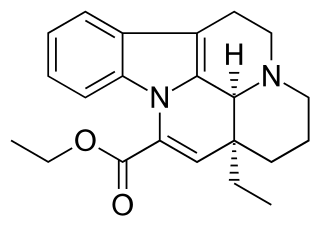

Vinpocetine is a synthetic derivative of the vinca alkaloid vincamine, differing by the removal of a hydroxyl group. Vincamine is extracted from either the seeds of Voacanga africana or the leaves of Vinca minor.

In re Amway Corp. is a 1979 ruling by the United States Federal Trade Commission concerning the business practices of Amway, a multi-level marketing (MLM) company. The FTC ruled that Amway was not an illegal pyramid scheme according strictly to the statutory definition of a pyramid scheme, but ordered Amway to cease price fixing and cease misrepresenting to its distributors (participants) the average participant's likelihood of financial security and material success.

Marketing ethics is an area of applied ethics which deals with the moral principles behind the operation and regulation of marketing. Some areas of marketing ethics overlap with media and public relations ethics.

FreeCreditScore.com, FreeCreditReport.com and Credit.com are websites owned by Experian Consumer Direct, a subsidiary of the credit bureau Experian. The sites offer users their personal credit reports from Experian on the condition that they sign up for Experian's Triple Advantage credit monitoring program for a fee. The credit report also comes with the user's PLUS credit score. The membership may be canceled with no charge within 7 days of signup by contacting the call center.

Consumer protection is the practice of safeguarding buyers of goods and services, and the public, against unfair practices in the marketplace. Consumer protection measures are often established by law. Such laws are intended to prevent businesses from engaging in fraud or specified unfair practices to gain an advantage over competitors or to mislead consumers. They may also provide additional protection for the general public which may be impacted by a product even when they are not the direct purchaser or consumer of that product. For example, government regulations may require businesses to disclose detailed information about their products—particularly in areas where public health or safety is an issue, such as with food or automobiles.

MyLife is an American information brokerage scam. The firm was founded by Jeffrey Tinsley in 2002 as Reunion.com and changed names following the 2008 merger with Wink.com.

The United States Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has been involved in oversight of the behavioral targeting techniques used by online advertisers since the mid-1990s. These techniques, initially called "online profiling", are now referred to as "behavioral targeting"; they are used to target online behavioral advertising (OBA) to consumers based on preferences inferred from their online behavior. During the period from the mid-1990s to the present, the FTC held a series of workshops, published a number of reports, and gave numerous recommendations regarding both industry self-regulation and Federal regulation of OBA. In late 2010, the FTC proposed a legislative framework for U.S. consumer data privacy including a proposal for a "Do Not Track" mechanism. In 2011, a number of bills were introduced into the United States Congress that would regulate OBA.

David C. Vladeck is the former director of the Bureau of Consumer Protection of the Federal Trade Commission, an independent agency of the United States government. He was appointed by the chairman of the FTC, Jon Leibowitz, on April 14, 2009, shortly after Leibowitz became chairman.

Vemma Nutrition Company was a privately held multi-level marketing company that sold dietary supplements. The company was shut down in 2015 by the FTC for engaging in deceptive practices and pyramid scheming.

TINA.org (TruthinAdvertising.org) is an independent, non-profit, advertising watchdog organization. TINA.org was founded in 2012 and received its initial funding from Karen Pritzker and Michael Vlock through their Seedlings Foundation, which supports programs that nourish the physical and mental health of children and families, and fosters an educated and engaged citizenship. TINA.org is headed by Bonnie Patten, who has served as its Executive Director since its founding.

United States v. Google Inc., No. 3:12-cv-04177, is a case in which the United States District Court for the Northern District of California approved a stipulated order for a permanent injunction and a $22.5 million civil penalty judgment, the largest civil penalty the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has ever won in history. The FTC and Google Inc. consented to the entry of the stipulated order to resolve the dispute which arose from Google's violation of its privacy policy. In this case, the FTC found Google liable for misrepresenting "privacy assurances to users of Apple's Safari Internet browser". It was reached after the FTC considered that through the placement of advertising tracking cookies in the Safari web browser, and while serving targeted advertisements, Google violated the 2011 FTC's administrative order issued in FTC v. Google Inc.

In addition to federal laws, each state has its own unfair competition law to prohibit false and misleading advertising. In California, one such statute is the Unfair Competition Law ("UCL"), Business and Professions Code §§ 17200 et seq. The UCL "borrows heavily from section 5 of the Federal Trade Commission Act" but has developed its own body of case law.