Akinwande Oluwole Babatunde Soyinka Hon. FRSL, known as Wole Soyinka, is a Nigerian playwright, novelist, poet, and essayist in the English language. He was awarded the 1986 Nobel Prize in Literature, for "in a wide cultural perspective and with poetic overtones fashioning the drama of existence", the first sub-Saharan African to be honoured in that category.

Palm wine, known by several local names, is an alcoholic beverage created from the sap of various species of palm tree such as the palmyra, date palms, and coconut palms. It is known by various names in different regions and is common in various parts of Africa, the Caribbean, South America, South Asia, Southeast Asia and Micronesia.

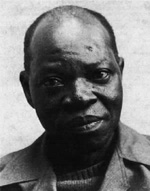

Chinua Achebe was a Nigerian novelist, poet, and critic who is regarded as a central figure of modern African literature. His first novel and magnum opus, Things Fall Apart (1958), occupies a pivotal place in African literature and remains the most widely studied, translated, and read African novel. Along with Things Fall Apart, his No Longer at Ease (1960) and Arrow of God (1964) complete the "African Trilogy". Later novels include A Man of the People (1966) and Anthills of the Savannah (1987). In the West, Achebe is often referred to as the "father of African literature", although he vigorously rejected the characterization.

Amos Tutuola was a Nigerian writer who wrote books based in part on Yoruba folk-tales.

Nigerian literature may be roughly defined as the literary writing by citizens of the nation of Nigeria for Nigerian readers, addressing Nigerian issues. This encompasses writers in a number of languages, including not only English but Igbo, Urhobo, Yoruba, and in the northern part of the county Hausa and Nupe. More broadly, it includes British Nigerians, Nigerian Americans and other members of the African diaspora.

Chief Daniel Olorunfẹmi Fágúnwà MBE, popularly known as D. O. Fágúnwà, was a Nigerian author of Yorùbá heritage who pioneered the Yorùbá language novel.

My Life in the Bush of Ghosts is a novel by Nigerian writer Amos Tutuola, published in 1954, It tells the story of a young West African boy who becomes lost in the wilderness, known as the bush, after fleeing from slave traders with his elder brother. The novel is presented as a collection of related narratives, although not always in chronological order, which adds to its surreal and dreamlike quality.

Palm wine is an alcoholic beverage.

African literature is literature from Africa, either oral ("orature") or written in African and Afro-Asiatic languages. Examples of pre-colonial African literature can be traced back to at least the fourth century AD. The best-known is the Kebra Negast, or "Book of Kings."

Yoruba literature is the spoken and written literature of the Yoruba people, one of the largest ethno-linguistic groups in Nigeria and the rest of Africa. The Yoruba language is spoken in Nigeria, Benin, and Togo, as well as in dispersed Yoruba communities throughout the world.

John Munonye was an Igbo writer and one of the most renowned Nigerian writers of the 20th century.

Elijah Kolawole Ogunmola was a Nigerian dramatist, actor, mime, director, and playwright. Ogunmola is also regarded as one of the most brilliant actors in Africa in the 1950s and ’60s.

Hopes and Impediments: Selected Essays, 1965-1987 is collection of essays by Chinua Achebe, published in 1988.

The Palm Wine Drinkard is the first solo mixtape by rapper Kool A.D., of the rap group Das Racist. Released in January 2012, it is the first of two mixtapes released by Kool A.D. that year, with 51 following in April. The mixtape takes its name from Amos Tutuola's novel The Palm-Wine Drinkard.

Tunde Kelani, popularly known as TK, is a Nigerian filmmaker. In a career spanning more than four decades, TK specialises in producing movies that promote Nigeria's rich cultural heritage and have a root in documentation, archiving, education, entertainment and promotion of the culture.

Bayo Adebowale is a Nigerian novelist, poet, professor, critic, librarian and founder of the African Heritage Library and Cultural Centre, Adeyipo, Ibadan Oyo State

A Wreath for Udomo is a 1956 novel by the South African novelist Peter Abrahams. The novel follows a London-educated black African, Michael Udomo, who returns to Africa to become a revolutionary leader in the fictional country of Panafrica and is eventually martyred. The novel explores a revolutionary politics, exploring the diversity of actors and political communities needed to overcome colonial oppression.

Wasinmi or Wasimi is an Egba town located on the Lagos-Abeokuta Expressway in Ewekoro local government of Ogun State. It is a few miles from Abeokuta. It is home to one of the oldest churches in the area, St. Michael's Anglican Church, and home to Odegbami International College and Sports Academy.

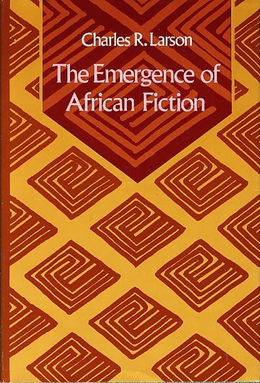

Charles Raymond Larson was an American scholar of literature, particularly of African literature. He published a number of anthologies of African literature, as well as literary criticism, and is seen as one of the founders of the study of African literature in the United States.

The Emergence of African Fiction is a 1972 academic monograph by American scholar Charles R. Larson. It was published initially by Indiana University Press, and again, in a slightly revised edition, in 1978 by Macmillan. Larson's study has elicited very different responses: it was praised as an early and important book in the study and appreciation of African literature in the West, but for others it remained stuck in a Eurocentric, even colonizing mode in which Western aesthetics were still the unspoken standard for artistic assessment.