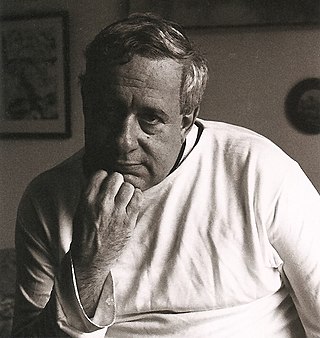

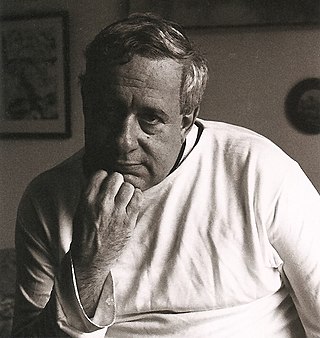

Jonathan Earl Franzen is an American novelist and essayist. His 2001 novel The Corrections drew widespread critical acclaim, earned Franzen a National Book Award, was a Pulitzer Prize for Fiction finalist, earned a James Tait Black Memorial Prize, and was shortlisted for the International Dublin Literary Award. His novel Freedom (2010) garnered similar praise and led to an appearance on the cover of Time magazine alongside the headline "Great American Novelist". Franzen's latest novel Crossroads was published in 2021, and is the first in a projected trilogy.

William Thomas Gaddis Jr. was an American novelist. The first and longest of his five novels, The Recognitions, was named one of TIME magazine's 100 best novels from 1923 to 2005 and two others, J R and A Frolic of His Own, won the annual U.S. National Book Award for Fiction. A collection of his essays was published posthumously as The Rush for Second Place (2002). The Letters of William Gaddis was published by Dalkey Archive Press in February 2013.

William Howard Gass was an American novelist, short story writer, essayist, critic, and philosophy professor. He wrote three novels, three collections of short stories, a collection of novellas, and seven volumes of essays, three of which won National Book Critics Circle Award prizes and one of which, A Temple of Texts (2006), won the Truman Capote Award for Literary Criticism. His 1995 novel The Tunnel received the American Book Award. His 2013 novel Middle C won the 2015 William Dean Howells Medal.

The Clementine literature is a late antique third-century Christian romance or "novel" containing a fictitious account of the conversion of Clement of Rome to Christianity, his subsequent life and travels with the apostle Peter and an account of how they became traveling companions, Peter's discourses, and finally Clement's family history and eventual reunion with his family. To reflect the pseudonymous nature of the authorship, the author is sometimes referred to as Pseudo-Clement. In all likelihood, the original text went by the name of Periodoi Petrou or Circuits of Peter; sometimes historians refer to it as the "Basic Writing" or "Grundschrift".

Art forgery is the creation and sale of works of art which are falsely credited to other, usually more famous artists. Art forgery can be extremely lucrative, but modern dating and analysis techniques have made the identification of forged artwork much simpler.

Dalkey Archive Press is an American publisher of fiction, poetry, foreign translations and literary criticism specializing in the publication or republication of lesser-known, often avant-garde works. The company has offices in Funks Grove, Illinois, in Dublin, and in London. The publisher is named for the novel The Dalkey Archive, by the Irish author Flann O'Brien. It is owned by nonprofit publisher Deep Vellum.

Cynthia Ozick is an American short story writer, novelist, and essayist.

How to Be Alone is a 2002 book collecting fourteen essays by American writer Jonathan Franzen.

Wittgenstein's Mistress by David Markson is a highly stylized, experimental novel in the tradition of Samuel Beckett. The novel is mainly a series of statements made in the first person; the protagonist is a woman named Kate who believes herself to be the last human on earth. Though her statements shift quickly from topic to topic, the topics often recur, and often refer to Western cultural icons, ranging from Zeno to Beethoven to Willem de Kooning. Readers familiar with Ludwig Wittgenstein's Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus will recognize stylistic similarities to that work.

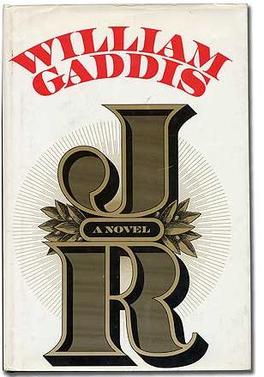

J R is a novel by William Gaddis published by Alfred A. Knopf in 1975. It tells the story of a schoolboy secretly amassing a fortune in penny stocks. J R won the National Book Award for Fiction in 1976. It was Gaddis' first novel since the 1955 publication of The Recognitions.

Carpenter's Gothic is the title of the third novel by American writer William Gaddis, published in 1985 by Viking. The title connotes a "Gothic" tale of haunted isolation, in a milieu stripped of all pretensions.

Alan Ansen was an American poet, playwright, and associate of Beat Generation writers. He was a widely read scholar who knew many languages. Ansen grew up on Long Island and was educated at Harvard. He worked as W. H. Auden's secretary and research assistant in 1948–49; he was the main author of the chronological tables in Auden's The Portable Greek Reader and Poets of the English Language.

Sheri Martinelli, was an American painter, poet, and muse.

Steven Moore is an American author and literary critic. Best known as the primary authority on the novelist William Gaddis, he is the author of the two-volume study The Novel: An Alternative History.

Fire the Bastards! was written by Jack Green and published in his magazine newspaper in 1962. It was an acerbic critique of the book reviewing industry.

jack green is the pseudonym of Christopher Carlisle Reid, an American literary critic who was a great defender of the work of William Gaddis. Reid—who took the name from a racing form after he quit his job to become a freelance critic—particularly admired Gaddis' 1955 novel The Recognitions, which flopped upon being published. Reid believed that the commercial failure of the hardcover edition of Gaddis' novel was the result of it having been panned by literary critics. Reid's faith in Gaddis was borne out when The Recognitions was chosen as one of TIME magazine's 100 best novels from 1923 to 2005.

The Review of Contemporary Fiction is a tri-quarterly journal published by Dalkey Archive Press. It features a variety of fiction, reviews and critical essays, with emph on literature that has an experimental, avant-garde or subversive bent. Founded in 1980 by the publisher John O'Brien, the Review of Contemporary Fiction originally focused upon American and British writers who had been overlooked by the critical establishment, and in this manner the Review succeeded in bringing new critical attention to writers such as William Gaddis, Gilbert Sorrentino, Paul Metcalf, Nicholas Mosley, Donald Barthelme, and many others. In 1984, in order to begin reprinting some of these authors, John O'Brien founded Dalkey Archive Press.

"Why Bother?", originally published as "Perchance to Dream: In the Age of Images, a Reason to Write Novels", is a literary essay by American novelist Jonathan Franzen. It is often referred to as "The Harper's Essay". First published in the April 1996 issue of Harper's magazine, the essay concerns the persistence of reading within the context of technological growth and distraction. Franzen recounts his meditations on the state and possibility of the novel form, often against the backdrop of his personal experience, eventually concluding that the novel still has potential cultural agency in the United States, and often gains it by paradoxical drives of both culture and author.

A Smuggler's Bible is Joseph McElroy's first novel. David Brooke—who talks of himself in a split-personality manner—narrates a framing tale that consists of him "smuggling" his essence into eight autobiographical manuscripts, although their connection with Brooke is not always clear. Brooke seems to deteriorate, while his fictions become more real.

"Mr. Difficult", subtitled "William Gaddis and the problem of hard-to-read books", is a 2002 essay by Jonathan Franzen that appeared in the 9/30/2002 issue of The New Yorker. It was reprinted in the paperback edition of How to Be Alone without the subtitle.