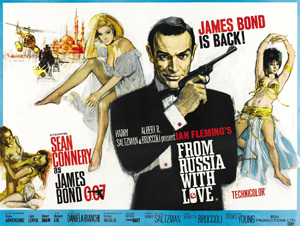

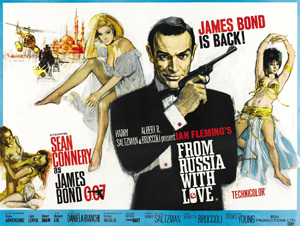

Sir Thomas Sean Connery was a Scottish actor. He was the first actor to portray fictional British secret agent James Bond on film, starring in seven Bond films between 1962 and 1983. Connery originated the role in Dr. No (1962) and continued starring as Bond in the Eon Productions films From Russia with Love (1963), Goldfinger (1964), Thunderball (1965), You Only Live Twice (1967) and Diamonds Are Forever (1971). Connery made his final appearance in the franchise in Never Say Never Again (1983), a non-Eon-produced Bond film.

Armageddon is a 1998 American science fiction disaster film produced and directed by Michael Bay, produced by Jerry Bruckheimer, and released by Touchstone Pictures. The film follows a group of blue-collar deep-core drillers sent by NASA to stop a gigantic asteroid on a collision course with Earth. It stars an ensemble cast consisting of Bruce Willis with Billy Bob Thornton, Ben Affleck, Liv Tyler, Will Patton, Steve Buscemi, William Fichtner, Owen Wilson, Michael Clarke Duncan, Keith David and Peter Stormare.

Alcatraz Island is a small island 1.25 miles (2.01 km) offshore from San Francisco, California, United States. The island was developed in the mid-19th century with facilities for a lighthouse, a military fortification, and a military prison. In 1934, the island was converted into a federal prison, Alcatraz Federal Penitentiary. The strong currents around the island and cold water temperatures made escape nearly impossible, and the prison became one of the most notorious in American history. The prison closed in 1963, and the island is now a major tourist attraction.

Time Bandits is a 1981 British fantasy adventure film co-written, produced, and directed by Terry Gilliam. It stars Sean Connery, John Cleese, Shelley Duvall, Ralph Richardson, Katherine Helmond, Ian Holm, Michael Palin, Peter Vaughan and David Warner. The film tells the story of a young boy taken on an adventure through time with a band of thieves who plunder treasure from various points in history.

Diamonds Are Forever is a 1971 spy film, the seventh in the James Bond series produced by Eon Productions. It is the sixth and final Eon film to star Sean Connery, who returned to the role as the fictional MI6 agent James Bond, having declined to reprise the role in On Her Majesty's Secret Service (1969).

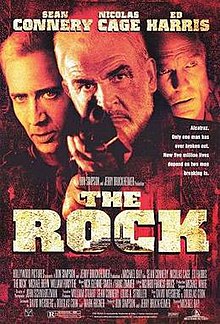

The Rock most often refers to:

Michael Benjamin Bay is an American film director and producer. He is best known for making big-budget, high-concept action films characterized by fast cutting, stylistic cinematography and visuals, and extensive use of special effects, including frequent depictions of explosions. The films he has produced and directed, which include Armageddon (1998), Pearl Harbor (2001) and the Transformers film series (2007–present), have grossed over US$7.8 billion worldwide, making him one of the most commercially successful directors in history.

Sir Richard Billing Dearlove is a retired British intelligence officer who was head of the British Secret Intelligence Service (MI6), a role known informally as "C", from 1999 until 6 May 2004. He was head of MI6 during the invasion of Iraq. He was criticised by the Iraq Inquiry for providing unverified intelligence about weapons of mass destruction to the Prime Minister, Tony Blair.

Mickey Blue Eyes is a 1999 American romantic comedy crime film directed by Kelly Makin. Hugh Grant stars as Michael Felgate, an English auctioneer living in New York City who becomes entangled in his soon-to-be father-in-law's mafia connections. Several of the minor roles are played by actors later featured in The Sopranos.

Escape from Alcatraz is a 1979 American prison action thriller film directed and co-produced by Don Siegel, written by Richard Tuggle, and starring Clint Eastwood alongside Patrick McGoohan, Fred Ward, Jack Thibeau, and Larry Hankin with Danny Glover appearing in his film debut.

You Only Live Twice is a 1967 spy film and the fifth in the James Bond series produced by Eon Productions, starring Sean Connery as the fictional MI6 agent James Bond. It is the first Bond film to be directed by Lewis Gilbert, who later directed the 1977 film The Spy Who Loved Me and the 1979 film Moonraker, both starring Roger Moore. The screenplay of You Only Live Twice was written by Roald Dahl, and loosely based on Ian Fleming's 1964 novel of the same name. It is the first James Bond film to discard most of Fleming's plot, using only a few characters and locations from the book as the background for an entirely new story.

Thunderball is a 1965 spy film and the fourth in the James Bond series produced by Eon Productions, starring Sean Connery as the fictional MI6 agent James Bond. It is an adaptation of the 1961 novel of the same name by Ian Fleming, which in turn was based on an original screenplay by Jack Whittingham devised from a story conceived by Kevin McClory, Whittingham, and Fleming. It was the third and final Bond film to be directed by Terence Young, with its screenplay by Richard Maibaum and John Hopkins.

From Russia with Love is a 1963 spy film and the second in the James Bond series produced by Eon Productions, as well as Sean Connery's second role as MI6 agent 007 James Bond.

Woman of Straw is a 1964 crime thriller directed by Basil Dearden and starring Gina Lollobrigida and Sean Connery. It was written by Robert Muller and Stanley Mann, adapted from the 1954 novel La Femme de paille by Catherine Arley.

Alcatraz Island has appeared many times in popular culture. Its appeal in film derives from its picturesque setting, natural beauty, isolation, and its history as a U.S. penitentiary – from which, officially, no prisoner ever successfully escaped.

In June 1962, inmates Clarence Anglin, John Anglin, and Frank Morris escaped from Alcatraz Federal Penitentiary, a maximum-security prison located on Alcatraz Island in San Francisco Bay, California, United States. Late on the night of June 11 or early morning of June 12, the three men tucked papier-mâché heads resembling their own likenesses into their beds, broke out of the main prison building via ventilation ducts and an unused utility corridor, and departed the island aboard an improvised inflatable raft to an uncertain fate. A fourth conspirator, Allen West, failed in his escape attempt and remained on the island.

The Iraq Inquiry was a British public inquiry into the nation's role in the Iraq War. The inquiry was announced in 2009 by Prime Minister Gordon Brown and published in 2016 with a public statement by Chilcot.

Sir John Anthony Chilcot was a British civil servant.

Sir Sean Connery (1930–2020) was a Scottish film actor and producer. He was the first actor to play the fictional secret agent James Bond in a theatrical film, starring in six EON Bond films between 1962 and 1971, and again in another non-EON Bond film in 1983. He was also known for his roles as Jimmy Malone in The Untouchables (1987), for which he won the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor; Mark Rutland in Marnie (1964); Juan Sánchez Villa-Lobos Ramírez in Highlander (1986); Henry Jones Sr. in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989); Captain Marko Aleksandrovich Ramius in The Hunt for Red October (1990); John Patrick Mason in The Rock; and Allan Quatermain in The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen (2003). Along with his Academy Award, he won two BAFTA Awards, three Golden Globes, and a Henrietta Award.