Historicism is an approach to explaining the existence of phenomena, especially social and cultural practices, by studying their history; that is, by studying the process by which they came about. The term is widely used in philosophy, anthropology, and sociology.

Max Horkheimer was a German philosopher and sociologist who was famous for his work in critical theory as a member of the Frankfurt School of social research. Horkheimer addressed authoritarianism, militarism, economic disruption, environmental crisis, and the poverty of mass culture using the philosophy of history as a framework. This became the foundation of critical theory. His most important works include Eclipse of Reason (1947), Between Philosophy and Social Science (1930–1938) and, in collaboration with Theodor Adorno, Dialectic of Enlightenment (1947). Through the Frankfurt School, Horkheimer planned, supported and made other significant works possible.

Talcott Parsons was an American sociologist of the classical tradition, best known for his social action theory and structural functionalism. Parsons is considered one of the most influential figures in sociology in the 20th century. After earning a PhD in economics, he served on the faculty at Harvard University from 1927 to 1973. In 1930, he was among the first professors in its new sociology department. Later, he was instrumental in the establishment of the Department of Social Relations at Harvard.

The term Homo economicus, or economic man, is the portrayal of humans as agents who are consistently rational and narrowly self-interested, and who pursue their subjectively defined ends optimally. It is a wordplay on Homo sapiens, used in some economic theories and in pedagogy.

The Frankfurt School is a school of thought in sociology and critical philosophy. It is associated with the Institute for Social Research founded at Goethe University Frankfurt in 1923. Formed during the Weimar Republic during the European interwar period, the first generation of the Frankfurt School was composed of intellectuals, academics, and political dissidents dissatisfied with the contemporary socio-economic systems of the 1930s; namely, capitalism, fascism, and communism.

Conflict theories are perspectives in political philosophy and sociology which argue that individuals and groups within society interact on the basis of conflict rather than agreement, while also emphasizing social psychology, historical materialism, power dynamics, and their roles in creating power structures, social movements, and social arrangements within a society. Conflict theories often draw attention to power differentials, such as class conflict, or a conflict continuum. Power generally contrasts historically dominant ideologies, economies, currencies or technologies. Accordingly, conflict theories represent attempts at the macro-level analysis of society.

Legal positivism is a school of thought of analytical jurisprudence developed largely by legal philosophers during the 18th and 19th centuries, such as Jeremy Bentham and John Austin. While Bentham and Austin developed legal positivist theory, empiricism provided the theoretical basis for such developments to occur. The most prominent legal positivist writer in English has been H. L. A. Hart.

Political sociology is an interdisciplinary field of study concerned with exploring how governance and society interact and influence one another at the micro to macro levels of analysis. Interested in the social causes and consequences of how power is distributed and changes throughout and amongst societies, political sociology's focus ranges across individual families to the state as sites of social and political conflict and power contestation.

Structural functionalism, or simply functionalism, is "a framework for building theory that sees society as a complex system whose parts work together to promote solidarity and stability".

Social research is research conducted by social scientists following a systematic plan. Social research methodologies can be classified as quantitative and qualitative.

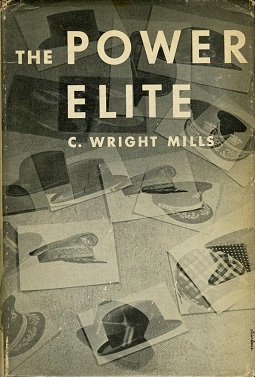

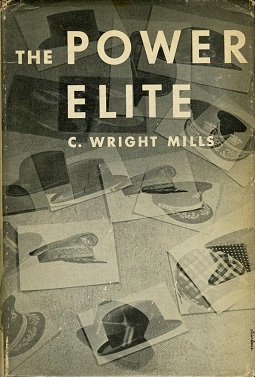

Charles Wright Mills was an American sociologist, and a professor of sociology at Columbia University from 1946 until his death in 1962. Mills published widely in both popular and intellectual journals, and is remembered for several books, such as The Power Elite, White Collar: The American Middle Classes, and The Sociological Imagination. Mills was concerned with the responsibilities of intellectuals in post–World War II society, and he advocated public and political engagement over disinterested observation. One of Mills's biographers, Daniel Geary, writes that Mills's writings had a "particularly significant impact on New Left social movements of the 1960s era." It was Mills who popularized the term New Left in the U.S. in a 1960 open letter, "Letter to the New Left".

Sociological imagination is a term used in the field of sociology to describe a framework for understanding social reality that places personal experiences within a broader social and historical context.

Sociology as a scholarly discipline emerged, primarily out of Enlightenment thought, as a positivist science of society shortly after the French Revolution. Its genesis owed to various key movements in the philosophy of science and the philosophy of knowledge, arising in reaction to such issues as modernity, capitalism, urbanization, rationalization, secularization, colonization and imperialism.

The Power Elite is a 1956 book by sociologist C. Wright Mills, in which Mills calls attention to the interwoven interests of the leaders of the military, corporate, and political elements of society and suggests that the ordinary citizen in modern times is a relatively powerless subject of manipulation by those three entities.

Positivism is a philosophical school that holds that all genuine knowledge is either true by definition or positive—meaning a posteriori facts derived by reason and logic from sensory experience. Other ways of knowing, such as intuition, introspection, or religious faith, are rejected or considered meaningless.

A sociological theory is a supposition that intends to consider, analyze, and/or explain objects of social reality from a sociological perspective, drawing connections between individual concepts in order to organize and substantiate sociological knowledge. Hence, such knowledge is composed of complex theoretical frameworks and methodology.

Feminist epistemology is an examination of epistemology from a feminist standpoint.

Sociology is the study of human society that focuses on society, human social behavior, patterns of social relationships, social interaction, and aspects of culture associated with everyday life. Regarded as a part of both the social sciences and humanities, sociology uses various methods of empirical investigation and critical analysis to develop a body of knowledge about social order and social change. Sociological subject matter ranges from micro-level analyses of individual interaction and agency to macro-level analyses of social systems and social structure. Applied sociological research may be applied directly to social policy and welfare, whereas theoretical approaches may focus on the understanding of social processes and phenomenological method.

Grand theory is a term coined by the American sociologist C. Wright Mills in The Sociological Imagination to refer to the form of highly abstract theorizing in which the formal organization and arrangement of concepts takes priority over understanding the social reality. In his view, grand theory is more or less separate from concrete concerns of everyday life and its variety in time and space.

A critical theory is any approach to humanities and social philosophy that focuses on society and culture to attempt to reveal, critique, and challenge power structures. With roots in sociology and literary criticism, it argues that social problems stem more from social structures and cultural assumptions rather than from individuals. Some hold it to be an ideology, others argue that ideology is the principal obstacle to human liberation. Critical theory finds applications in various fields of study, including psychoanalysis, film theory, literary theory, cultural studies, history, communication theory, philosophy, and feminist theory.