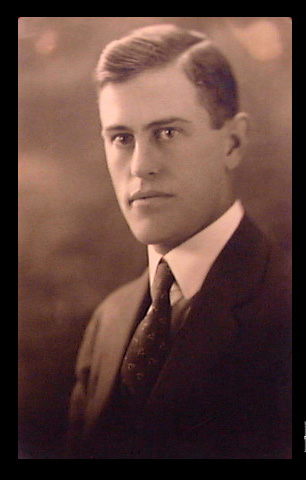

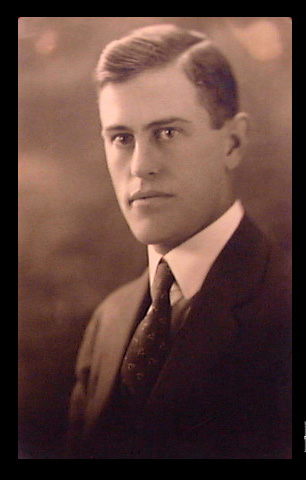

Charles Augustus Lindbergh was an American aviator, military officer, author, inventor, and activist. On May 20–21, 1927, Lindbergh made the first nonstop flight from New York City to Paris, a distance of 3,600 miles (5,800 km), flying alone for 33.5 hours. His aircraft, the Spirit of St. Louis, was designed and built by the Ryan Airline Company specifically to compete for the Orteig Prize for the first flight between the two cities. Although not the first transatlantic flight, it was the first solo transatlantic flight and the longest at the time by nearly 2,000 miles. It became known as one of the most consequential flights in history and ushered in a new era of air transportation between parts of the globe.

The Orteig Prize was a reward offered to the first Allied aviator(s) to fly non-stop from New York City to Paris or vice versa. Several famous aviators made unsuccessful attempts at the New York–Paris flight before the relatively unknown American Charles Lindbergh won the prize in 1927 in his aircraft Spirit of St. Louis. However, a number of people died who were competing to win the prize. Six men died in three separate crashes, and another three were injured in a fourth crash. The Prize occasioned considerable investment in aviation, sometimes many times the value of the prize itself, and advancing public interest and the level of aviation technology.

The Spirit of St. Louis is the custom-built, single-engine, single-seat, high-wing monoplane that was flown by Charles Lindbergh on May 20–21, 1927, on the first solo nonstop transatlantic flight from Long Island, New York, to Paris, France, for which Lindbergh won the $25,000 Orteig Prize.

Raymond Orteig was a French American hotel owner in New York City in the early 20th century. He is best known for setting up the $25,000 Orteig Prize in 1919 for the first non-stop transatlantic flight between New York City and Paris, which was claimed by Charles Lindbergh eight years later in 1927.

Erik Robbins Lindbergh is an American aviator, adventurer, and artist. He is the grandson of pioneering aviator Charles Lindbergh, the first person to fly non-stop and solo between New York and Paris in 1927. In 2002, Erik Lindbergh honored the 75th anniversary of his grandfather's historic flight by retracing the journey in a single-engine Lancair aircraft. The journey was documented by the History Channel, raised over one million dollars for three charities, garnered half a billion media impressions for the X PRIZE Foundation and helped to jump-start the private Spaceflight industry. The flight prompted a call from United States President George W. Bush for inspiring the country after the tragedy of September 11.

The Spirit of St. Louis is a 1957 aviation biography film in CinemaScope and Warnercolor from Warner Bros., directed by Billy Wilder, produced by Leland Hayward, and starring James Stewart as Charles Lindbergh. The screenplay was adapted by Charles Lederer, Wendell Mayes, and Billy Wilder from Lindbergh's 1953 autobiographical account of his historic flight, which won the Pulitzer Prize in 1954.

The America was a Fokker C-2 trimotor monoplane that was flown in 1927 by Richard E. Byrd, Bernt Balchen, George Otto Noville, and Bert Acosta on their transatlantic flight.

Clarence Duncan Chamberlin was an American pioneer of aviation, being the second man to pilot a fixed-wing aircraft across the Atlantic Ocean, from New York to the European mainland, while carrying the first transatlantic passenger.

Charles Albert Levine was the first passenger aboard a transatlantic flight. He was ready to cross the Atlantic to claim the Orteig prize but a court battle over who was going to be in the airplane allowed Charles Lindbergh to leave first.

Donald Albert Hall was an American pioneering aeronautical engineer and aircraft designer who is most famous for having designed the Spirit of St. Louis.

L'Oiseau Blanc was a French Levasseur PL.8 biplane that disappeared in 1927 during an attempt to make the first non-stop transatlantic flight between Paris and New York City to compete for the Orteig Prize. French World War I aviation heroes Charles Nungesser and François Coli took off from Paris on 8 May 1927 and were last seen over Ireland. Less than two weeks later, Charles Lindbergh successfully made the New York–Paris journey and claimed the prize in the Spirit of St. Louis.

George Otto Noville, also known as "Noville" and "Rex," was a pioneer in polar and trans-Atlantic aviation in the 1920s, and winner of the Distinguished Flying Cross. He served with Commander Richard E. Byrd on the historic 1926 flight to the North Pole, as third in command. He was flight engineer on the America, and was executive officer of Byrd's Second Antarctic Exploration 1933-35. Mount Noville and Noville Peninsula in Antarctica are named after him.

The Wright-Bellanca WB-2, was a high wing monoplane aircraft designed by Giuseppe Mario Bellanca, initially for Wright Aeronautical then later Columbia Aircraft Corp.

Lloyd Wilson Bertaud was an American aviator. Bertaud was selected to be the copilot in the WB-2 Columbia attempting the transatlantic crossing for the Orteig Prize in 1927. Aircraft owner Charles Albert Levine wanted to fly in his place, and an injunction by Bertaud against Levine prevented the flight. The prize was won by the aviator Charles Lindbergh.

The following events occurred in June 1927:

The Lindbergh Boom (1927–1929) is a period of rapid interest in aviation following the awarding of the Orteig Prize to Charles Lindbergh for his 1927 non-stop solo transatlantic flight in the Spirit of St. Louis. The Lindbergh Boom occurred during the interwar period between World War I and World War II, where aviation development was fueled by commercial interests rather than wartime necessity. During this period, dozens of companies were formed to create airlines, and aircraft for a new age in aviation. Many of the fledgling companies funded by stock went under as quick as they started as the stock that capitalized them plummeted in value following the Wall Street Crash of 1929. The Great Depression dried up the market for new aircraft, causing many aircraft companies to go into bankruptcy or get consolidated by larger entities. Air racing, record attempts, and barnstorming remained popular, as aviators tried to recapture the prizes and publicity of Lindbergh's Transatlantic flight.

Wooster and Davis -- Lieutenant Stanton Hall Wooster and Lieutenant Commander Noel Guy Davis were two United States Navy (USN) airmen who made an attempt to fly the Atlantic Ocean from New York-to-Paris in the spring of 1927. The men were trying to win the $25,000 dollar Orteig Prize offered by New York hotelier Raymond Orteig for the first nonstop flight between New York and Paris. Competitors for the prize were French World War One ace Rene Fonck and his crew of three, USN Commander Richard Evelyn Byrd, Clarence Chamberlain w/plane owner Charles Levine, and a young airmail pilot named Charles Lindbergh. On the Paris side of the Atlantic their competitors were another World War One French ace, Charles Nungesser, and his navigator Francois Coli.

"WE" is an autobiographical account by Charles A. Lindbergh (1902–1974) about his life and the events leading up to and including his May 1927 New York to Paris solo trans-Atlantic flight in the Spirit of St. Louis, a custom-built, single engine, single-seat Ryan monoplane. It was first published on July 27, 1927 by G.P. Putnam's Sons in New York.

Harlan Albert "Bud" Gurney was a pioneer American mail pilot and airline pilot. He is also known as one of Charles Lindbergh's oldest friends.

Hotel Lafayette was a hotel located on University Place in the Greenwich Village neighborhood of Manhattan, New York City. It was founded by Raymond Orteig in 1902. The hotel was particularly known for its restaurant, the Café Lafayette, and drew its clientele from New York's French expatriates and the bohemians of Greenwich Village. John Reed described the hotel as "the real link between the old Village and the new, since it was the cradle of artistic life in New York." After Orteig's retirement in 1929, the 65-room hotel and its restaurant were run by his sons until its closure in 1949. The building was demolished in the late 1950s.