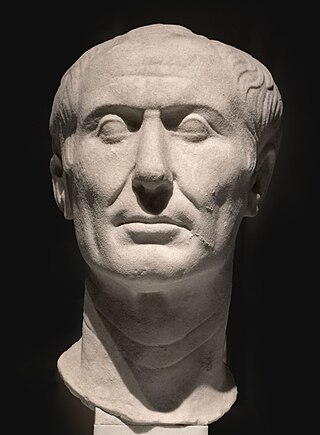

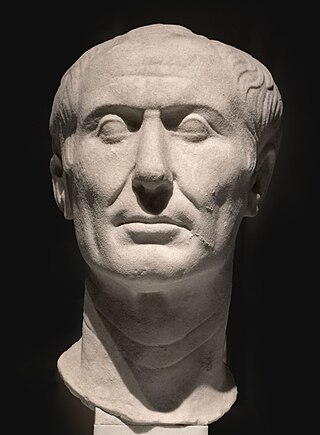

Gaius Julius Caesar was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, and subsequently became dictator from 49 BC until his assassination in 44 BC. He played a critical role in the events that led to the demise of the Roman Republic and the rise of the Roman Empire.

Marcus Antonius, commonly known in English as Mark Antony, was a Roman politician and general who played a critical role in the transformation of the Roman Republic from a constitutional republic into the autocratic Roman Empire.

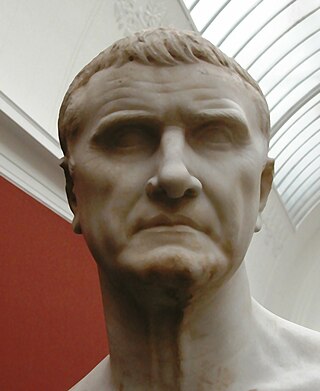

Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus, known in English as Pompey or Pompey the Great, was a Roman general and statesman. He played a significant role in the transformation of Rome from republic to empire. Early in his career, he was a partisan and protégé of the Roman general and dictator Sulla; later, he became the political ally, and finally the enemy, of Julius Caesar.

The 1st century BC, also known as the last century BC and the last century BCE, started on the first day of 100 BC and ended on the last day of 1 BC. The AD/BC notation does not use a year zero; however, astronomical year numbering does use a zero, as well as a minus sign, so "2 BC" is equal to "year –1". 1st century AD follows.

This article concerns the period 49 BC – 40 BC.

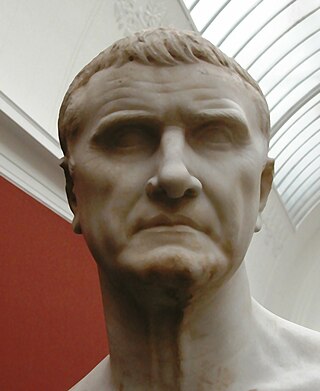

Marcus Licinius Crassus was a Roman general and statesman who played a key role in the transformation of the Roman Republic into the Roman Empire. He is often called "the richest man in Rome."

The Tragedy of Julius Caesar (First Folio title: The Tragedie of Ivlivs Cæsar), often abbreviated as Julius Caesar, is a history play and tragedy by William Shakespeare first performed in 1599.

Legio XIII Gemina, in English the 13th Twin Legion was a legion of the Imperial Roman army. It was one of Julius Caesar's key units in Gaul and in the civil war, and was the legion with which he crossed the Rubicon in January, perhaps the 10th, 49 BC. The legion appears to have still been in existence in the 5th century AD. Its symbol was the lion.

Decimus Junius Brutus Albinus was a Roman general and politician of the late republican period and one of the leading instigators of Julius Caesar's assassination. He had previously been an important supporter of Caesar in the Gallic Wars and in the civil war against Pompey. Decimus Brutus is often confused with his distant cousin and fellow conspirator, Marcus Junius Brutus.

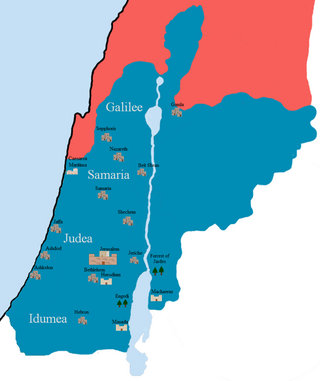

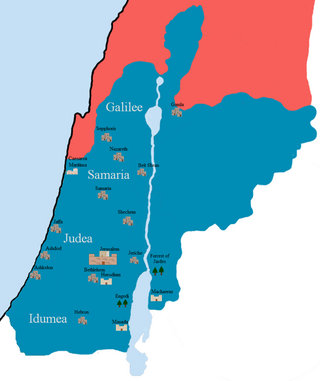

Antipater I the Idumaean was the founder of the Herodian Dynasty and father of Herod the Great. According to Josephus, he was the son of Antipas and had formerly held that name.

Commentarii de Bello Civili(Commentaries on the Civil War), or Bellum Civile, is an account written by Julius Caesar of his war against Gnaeus Pompeius and the Roman Senate. It consists of three books covering the events of 49–48 BC, from shortly before Caesar's invasion of Italy to Pompey's defeat at the Battle of Pharsalus and flight to Egypt. It was preceded by the much longer account of Caesar's campaigns in Gaul and was followed by similar works covering the ensuing wars against the remnants of Pompey's armies in Egypt, North Africa, and Spain. Caesar's authorship of the Commentarii de Bello Civili is not disputed, while the three later works are believed to have been written by contemporaries of Caesar.

Cilician pirates dominated the Mediterranean Sea from the 2nd century BC until their suppression by Pompey in 67–66 BC. Because there were notorious pirate strongholds in Cilicia, on the southern coast of Asia Minor, the term "Cilician" was long used to generically refer to any pirates in the Mediterranean.

The False One is a late Jacobean stage play by John Fletcher and Philip Massinger, though formerly placed in the Beaumont and Fletcher canon. It was first published in the first Beaumont and Fletcher folio of 1647.

Lucius Septimius was a Roman soldier and mercenary who is principally remembered as one of the assassins of the triumvir Pompey the Great. At the time of the assassination Septimius was serving the Ptolemies of Egypt as a mercenary. He was dispatched with orders to murder Pompey by Ptolemy XIII's advisors who wanted to win the favour of Julius Caesar for their king.

The Gabiniani were 2000 Roman legionaries and 500 cavalrymen stationed in Egypt by the Roman general Aulus Gabinius after he had reinstated the Pharaoh Ptolemy XII Auletes on the Egyptian throne in 55 BC. The soldiers were left to protect the King, but they soon adopted the manners of their new country and became completely alienated from the Roman Republic. After the death of Auletes in 51 BC, they helped his son Ptolemy XIII in his power struggle against his sister Cleopatra and even involved Julius Caesar, the supporter of Cleopatra, during Caesar's Civil War up to the siege of Alexandria in violent battles.

The Herodian Kingdom of Judea was a client state of the Roman Republic from 37 BCE, when Herod the Great, who had been appointed "King of the Jews" by the Roman Senate in 40/39 BCE, took actual control over the country. When Herod died in 4 BCE, the kingdom was divided among his sons into the Herodian Tetrarchy.

The Curia of Pompey, sometimes referred to as the Curia Pompeia, was one of several named meeting halls from Republican Rome of historic significance. A curia was a designated structure for meetings of the senate. The Curia of Pompey was located at the entrance to the Theater of Pompey. While the main senate house was being moved from the Curia Cornelia to a new Curia Julia, the senate would meet in this smaller building, which is best known as the place that members of the Roman Senate murdered Gaius Julius Caesar.

Lucius Vorenus and Titus Pullo were two Roman centurions mentioned in the personal writings of Julius Caesar. Although it is sometimes stated they were members of the 11th Legion, Caesar never states the number of the legion concerned, giving only the words in ea legione. All that is known is that the legion in which they served under Caesar was one commanded at the time by Quintus Cicero.

Antistia was a Roman woman and the first of the five wives of Gnaeus Pompeius, later known as Pompey the Great.