Henry Fielding was an English writer and magistrate known for the use of humour and satire in his works. His 1749 comic novel The History of Tom Jones, a Foundling was a seminal work in the genre. Along with Samuel Richardson, Fielding is seen as the founder of the traditional English novel. He also played an important role in the history of law enforcement in the United Kingdom, using his authority as a magistrate to found the Bow Street Runners, London's first professional police force.

Tom Thumb is a character of English folklore. The History of Tom Thumb was published in 1621 and was the first fairy tale printed in English. Tom is no bigger than his father's thumb, and his adventures include being swallowed by a cow, tangling with giants, and becoming a favourite of King Arthur. The earliest allusions to Tom occur in various 16th-century works such as Reginald Scot's Discovery of Witchcraft (1584), where Tom is cited as one of the supernatural folk employed by servant maids to frighten children. Tattershall in Lincolnshire, England, reputedly has the home and grave of Tom Thumb.

Chrononhotonthologos is a satirical play by the English poet and songwriter Henry Carey from 1734. Although the play has been seen as nonsense verse, it was also seen and celebrated at the time as a satire on Robert Walpole and Queen Caroline, wife of George II.

Augustan drama can refer to the dramas of Ancient Rome during the reign of Caesar Augustus, but it most commonly refers to the plays of Great Britain in the early 18th century, a subset of 18th-century Augustan literature. King George I referred to himself as "Augustus," and the poets of the era took this reference as apropos, as the literature of Rome during Augustus moved from historical and didactic poetry to the poetry of highly finished and sophisticated epics and satire.

James Ralph was an American-born English political writer, historian, reviewer, and Grub Street hack writer known for his works of history and his position in Alexander Pope's Dunciad B. His History of England in two volumes (1744–46) and The Case of the Authors by Profession of 1758 became the dominant narratives of their time.

An Essay on the Art of Ingeniously Tormenting was a conduct book written by Jane Collier and published in 1753. The Essay was Collier's first work, and operates as a satirical advice book on how to nag. It was modelled after Jonathan Swift's satirical essays, and is intended to "teach" a reader the various methods for "teasing and mortifying" one's acquaintances. It is divided into two sections that are organised for "advice" to specific groups, and it is followed by "General Rules" for all people to follow.

The early plays of Henry Fielding mark the beginning of Fielding's literary career. His early plays span the time period from his first production in 1728 to the beginning of the Actor's Rebellion of 1733, a strife within the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane that divided the theatrical community and threatened to disrupt London stage performances. These plays introduce Fielding's take on politics, gender, and morality and serve as an early basis for how Fielding develops his ideas on these matters throughout his career.

Love in Several Masques is a play by Henry Fielding that was first performed on 16 February 1728 at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane. The moderately received play comically depicts three lovers trying to pursue their individual beloveds. The beloveds require their lovers to meet their various demands, which serves as a means for Fielding to introduce his personal feelings on morality and virtue. In addition, Fielding introduces criticism of women and society in general.

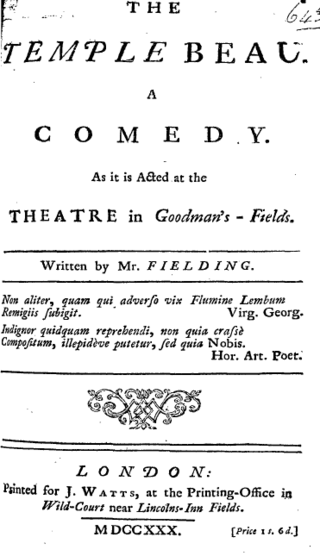

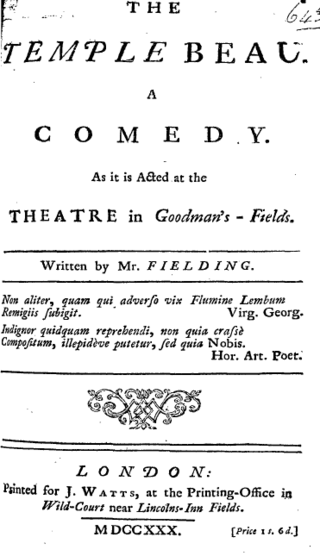

The Temple Beau is a play by Henry Fielding. It was first performed on 26 January 1730, at Goodman's Fields after it was rejected by the Theatre Royal. The play, well received at Goodman's Fields, depicts a young law student forsaking his studies for pleasure. By portraying hypocrisy in a comedic manner, Fielding shifts his focus from a discussion of love and lovers.

The Author's Farce and the Pleasures of the Town is a play by the English playwright and novelist Henry Fielding, first performed on 30 March 1730 at the Little Theatre, Haymarket. Written in response to the Theatre Royal's rejection of his earlier plays, The Author's Farce was Fielding's first theatrical success. The Little Theatre allowed Fielding the freedom to experiment, and to alter the traditional comedy genre. The play ran during the early 1730s and was altered for its run starting 21 April 1730 and again in response to the Actor Rebellion of 1733. Throughout its life, the play was coupled with several different plays, including The Cheats of Scapin and Fielding's Tom Thumb.

Tom Thumb is a play written by Henry Fielding as an addition to The Author's Farce. It was added on 24 April 1730 at Haymarket. It is a low tragedy about a character who is small in both size and status who is granted the hand of a princess in marriage. This infuriates the queen and a member of the court and the play chronicles their attempts to ruin the marriage.

Rape upon Rape; or, The Justice Caught in his own Trap, also known as The Coffee-House Politician, is a play by Henry Fielding. It was first performed at the Haymarket Theatre on 23 June 1730. The play is a love comedy that depicts the corruption rampant in politics and in the justice system. When two characters are accused of rape, they deal with the corrupt judge in separate manners. Though the play was influenced by the rape case of Colonel Francis Charteris, it used "rape" as an allegory to describe all abuses of freedom, as well as the corruption of power, though it was meant in a comedic, farcical manner.

The Letter Writers Or, a New Way to Keep a Wife at Home is a play by Henry Fielding and was first performed on 24 March 1731 at Haymarket with its companion piece The Tragedy of Tragedies. It is about two merchants who strive to keep their wives faithful. Their efforts are unsuccessful, however, until they catch the man who their wives are cheating with.

The Welsh Opera is a play by Henry Fielding. First performed on 22 April 1731 in Haymarket, the play replaced The Letter Writers and became the companion piece to The Tragedy of Tragedies. It was also later expanded into The Grub-Street Opera. The play's purported author is Scriblerus Secundus who is also a character in the play. This play is about Secundus' role in writing two (Fielding) plays: The Tragedy of Tragedies and The Welsh Opera.

The Grub Street Opera is a play by Henry Fielding that originated as an expanded version of his play The Welsh Opera. It was never put on for an audience and is Fielding's single print-only play. As in The Welsh Opera, the author of the play is identified as Scriblerus Secundus. Secundus also appears in the play and speaks of his role in composing the plays. In The Grub Street Opera the main storyline involves two men and their rival pursuit of women.

The Lottery is a play by Henry Fielding and was a companion piece to Joseph Addison's Cato. As a ballad opera, it contained 19 songs and was a collaboration with Mr Seedo, a musician. It first ran on 1 January 1732 at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane. The play tells the story of a man in love with a girl. She claims she has won a lottery, however, making another man pursue her for the fortune and forcing her original suitor to pay off the other for her hand in marriage, though she does not win.

The Old Debauchees, originally titled The Despairing Debauchee, was a play written by Henry Fielding. It originally appeared with The Covent-Garden Tragedy on 1 June 1732 at the Royal Theatre, Drury Lane and was later revived as The Debauchees; or, The Jesuit Caught. The play tells the story of Catholic priest's attempt to manipulate a man to seduce the man's daughter, ultimately unsuccessfully.

The Covent-Garden Tragedy is a play by Henry Fielding that first appeared on 1 June 1732 at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane alongside The Old Debauchees. It is about a love triangle in a brothel involving two prostitutes. While they are portrayed satirically, they are imbued with sympathy as their relationship develops.

The Mock Doctor: or The Dumb Lady Cur'd is a play by Henry Fielding and first ran on 23 June 1732 at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane. It served as a replacement for The Covent-Garden Tragedy and became the companion play to The Old Debauchees. It tells the exploits of a man who pretends to be a doctor at his wife's requests.

The Golden Rump is a farcical play of unknown authorship said to have been written in 1737. It acted as the chief trigger for the Theatrical Licensing Act of 1737. The play has never been performed on stage or published in print. No manuscript of the play survives, casting some doubt over whether it ever existed in full at all. The authorship of the play has often been ascribed to Henry Fielding, at that time a popular and prolific playwright who often turned his incisive satire against the monarch, George II, and particularly the "prime minister", Sir Robert Walpole. Modern literary historians, however, increasingly embrace the opinion that The Golden Rump may have been secretly commissioned by Walpole himself in a successful bid to get his Bill for theatrical licensing passed before the legislature.