Fra Angelico, OP was a Dominican friar and Italian painter of the Early Renaissance, described by Giorgio Vasari in his Lives of the Artists as having "a rare and perfect talent". He earned his reputation primarily for the series of frescoes he made for his own friary, San Marco, in Florence, then worked in Rome and other cities. All his known work is of religious subjects.

Masaccio, born Tommaso di Ser Giovanni di Simone, was a Florentine artist who is regarded as the first great Italian painter of the Quattrocento period of the Italian Renaissance. According to Vasari, Masaccio was the best painter of his generation because of his skill at imitating nature, recreating lifelike figures and movements as well as a convincing sense of three-dimensionality. He employed nudes and foreshortenings in his figures. This had seldom been done before him.

Masolino da Panicale was an Italian painter. His best known works are probably his collaborations with Masaccio: Madonna with Child and St. Anne (1424) and the frescoes in the Brancacci Chapel (1424–1428).

The Expulsion from the Garden of Eden is a fresco by the Italian Early Renaissance artist Masaccio. The fresco is a single scene from the cycle painted around 1425 by Masaccio, Masolino and others on the walls of the Brancacci Chapel in the church of Santa Maria del Carmine in Florence. It depicts the expulsion of Adam and Eve from the garden of Eden, from the biblical Book of Genesis chapter 3, albeit with a few differences from the canonical account.

The Brancacci Chapel is a chapel in the Church of Santa Maria del Carmine in Florence, central Italy. It is sometimes called the "Sistine Chapel of the early Renaissance" for its painting cycle, among the most famous and influential of the period. Construction of the chapel was commissioned by Felice Brancacci and begun in 1422. The paintings were executed over the years 1425 to 1427. Public access is currently gained via the neighbouring convent, designed by Brunelleschi. The church and the chapel are treated as separate places to visit and as such have different opening times and it is quite difficult to see the rest of the church from the chapel.

Florentine painting or the Florentine School refers to artists in, from, or influenced by the naturalistic style developed in Florence in the 14th century, largely through the efforts of Giotto di Bondone, and in the 15th century the leading school of Western painting. Some of the best known painters of the earlier Florentine School are Fra Angelico, Botticelli, Filippo Lippi, the Ghirlandaio family, Masolino, and Masaccio.

Santa Maria del Carmine is a church of the Carmelite Order, in the Oltrarno district of Florence, in Tuscany, Italy. It is famous as the location of the Brancacci Chapel housing outstanding Renaissance frescoes by Masaccio and Masolino da Panicale, later finished by Filippino Lippi.

Italian Renaissance painting is the painting of the period beginning in the late 13th century and flourishing from the early 15th to late 16th centuries, occurring in the Italian Peninsula, which was at that time divided into many political states, some independent but others controlled by external powers. The painters of Renaissance Italy, although often attached to particular courts and with loyalties to particular towns, nonetheless wandered the length and breadth of Italy, often occupying a diplomatic status and disseminating artistic and philosophical ideas.

This article about the development of themes in Italian Renaissance painting is an extension to the article Italian Renaissance painting, for which it provides additional pictures with commentary. The works encompassed are from Giotto in the early 14th century to Michelangelo's Last Judgement of the 1530s.

Felice di Michele Brancacci was a Florentine silk merchant, best known for commissioning the decoration of the Brancacci Chapel. The nephew and heir of Piero di Piuvichese Brancacci, he was involved in Mediterranean silk trade, and also acted as a diplomat.

The coin in the fish's mouth is one of the miracles of Jesus, recounted in the Gospel of Matthew 17:24–27.

The Last Supper of Jesus and the Twelve Apostles has been a popular subject in Christian art, often as part of a cycle showing the Life of Christ. Depictions of the Last Supper in Christian art date back to early Christianity and can be seen in the Catacombs of Rome.

The Delivery of the Keys, or Christ Giving the Keys to Saint Peter is a fresco by the Italian Renaissance painter Pietro Perugino which was produced in 1481–1482 and is located in the Sistine Chapel, Rome.

The Funeral of St. Jerome is a painting by the Italian Renaissance painter Filippo Lippi of Saint Jerome's funeral. It is housed in the Museo dell'Opera del Duomo next to the Cathedral of Prato, central Italy.

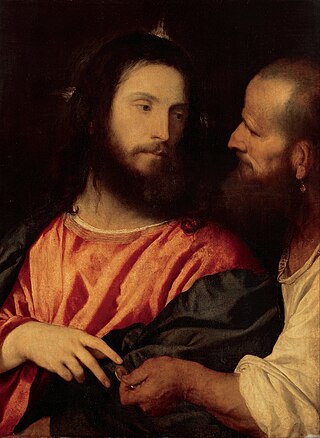

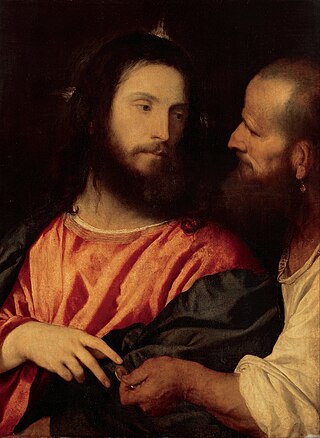

The Tribute Money is a panel painting in oils of 1516 by the Italian late Renaissance artist Titian, now in the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister in Dresden, Germany. It depicts Christ and a Pharisee at the moment in the Gospels when Christ is shown a coin and says "Render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar's, and unto God the things that are God's". It is signed "Ticianus F.[ecit]", painted on the trim of the left side of the Pharisee's collar.

Tribute Money may refer to:

The Navicella or Bark of St. Peter, of Old Saint Peter's Basilica in Rome, was a large and famous mosaic by Giotto di Bondone that occupied a large part of the wall above the entrance arcade, facing the main facade of the basilica across the courtyard. It depicted the version from the Gospel of Matthew of Christ walking on the water, the only one of the three gospel accounts where Saint Peter is summoned to join him. It was almost entirely destroyed during the construction of the new Saint Peter's Basilica in the 17th century, but fragments were preserved from the sides of the composition, and what is effectively a new work, incorporating some original fragments, was restored to a position at the centre of the portico of the new building in 1675.

Andrea di Giusto, rarely also known as Andrea Manzini or Andrea di Giusto Manzini was a Florentine painter of the late Gothic to early Renaissance style in Florence and its surrounding countryside. Andrea was heavily influenced by masters Lorenzo Monaco, Bicci di Lorenzo, Masaccio, and Fra Angelico, and tended to mix and match the motifs and techniques of these artists in his own work. Andrea was an eclectic painter and is considered a minor master of Florentine early Renaissance art. Andrea trained under Bicci di Lorenzo as a Garzone. He painted his most significant works, three altarpieces, in the Florentine contado, or countryside; these altarpieces were created for Sant’Andrea a Ripalta in Figline, Santa Margarita in Cortona, and the Badia degli Olivetani di San Bartolomeo alle Sacce near Prato. Aside from his major altarpieces, Andrea painted several Frescoes over the course of his career. He, along with other minor masters, are also known to have provided several different types of art, including triptychs and frescoes, for Romanesque pievi, or rural churches with baptistries. Moreover, he was well known for several types of smaller craft objects, such as small tabernacles. He is said to have worked between 1420 and 1424 under Bicci di Lorenzo on paintings for Santa Maria Nuova. He is said to have worked with Masaccio in painting the Life of San Giuliano for the Polyptych of Pisa, including the painting of the Madonna and Child, in 1426. He also appears to have collaborated in 1445 with Paolo Uccello in the Capella dell'Assunta in the Prato Cathedral. In 1428, he is listed as a member of the Arte dei Medici e Speziali guild in Florence as "Andrea di Giusto di Giovanni Bugli". His son, Giusto d'Andrea, was also a painter and worked with Neri di Bicci and Benozzo Gozzoli. Andrea died in Florence in 1450.

The Annunciation of Masolino is a tempera on panel painting dated to c. 1423–1424 or c. 1427–1429. It is in the collection of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.