Related Research Articles

East St. Louis is a city in St. Clair County, Illinois. It is directly across the Mississippi River from downtown St. Louis, Missouri, and the Gateway Arch National Park. East St. Louis is in the Metro-East region of Southern Illinois. Once a bustling industrial center, like many cities in the Rust Belt, East St. Louis was severely affected by the loss of jobs due to the flight of the population to the suburbs during the riots of the late 1960s. In 1950, East St. Louis was the fourth-largest city in Illinois when its population peaked at 82,366. As of the 2020 census, the city had a population of 18,469, less than one-quarter of the 1950 census and a decline of almost one third since 2010.

Race-integration busing in the United States was the practice of assigning and transporting students to schools within or outside their local school districts in an effort to diversify the racial make-up of schools. While the 1954 U.S. Supreme Court landmark decision in Brown v. Board of Education declared racial segregation in public schools unconstitutional, many American schools continued to remain largely uni-racial due to housing inequality. In an effort to address the ongoing de facto segregation in schools, the 1971 Supreme Court decision, Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, ruled that the federal courts could use busing as a further integration tool to achieve racial balance.

Detroit, the largest city in the state of Michigan, was settled in 1701 by French colonists. It is the first European settlement above tidewater in North America. Founded as a New France fur trading post, it began to expand during the 19th century with American settlement around the Great Lakes. By 1920, based on the booming auto industry and immigration, it became a world-class industrial powerhouse and the fourth-largest city in the United States. It held that standing through the mid-20th century.

The White House of the Confederacy is a historic house located in the Court End neighborhood of Richmond, Virginia. Built in 1818, it was the main executive residence of the sole President of the Confederate States of America, Jefferson Davis, from August 1861 until April 1865. It was viewed as the Confederate States counterpart to the White House in Washington, D.C. It currently sits on the campus of Virginia Commonwealth University.

The East St. Louis massacre was a series of violent attacks on African Americans by white Americans in East St. Louis, Illinois between late May and early July of 1917. These attacks also displaced 6,000 African Americans and led to the destruction of approximately $400,000 worth of property. They occurred in East St. Louis, an industrial city on the east bank of the Mississippi River, directly opposite the city of St. Louis, Missouri. The July 1917 episode in particular was marked by white-led violence throughout the city. The multi-day rioting has been described as the "worst case of labor-related violence in 20th-century American history", and among the worst racial riots in U.S. history.

The Commonwealth Education Trust was a registered charity established in 2007 as the successor trust to the Commonwealth Institute. The trust focuses on primary and secondary education and the training of teachers and invests on educational products and services to achieve both a beneficial and a financial reward to fund future charitable initiatives.

Smoketown is a neighborhood one mile (1.6 km) southeast of downtown Louisville, Kentucky. Smoketown has been a historically black neighborhood since the Civil War. It is the only neighborhood in the city that has had such a continuous presence. Smoketown is bounded by Broadway, CSX railroad tracks, Kentucky Street, and I-65.

Facilities and services such as housing, healthcare, education, employment, and transportation have been systematically separated in the United States on racial categorizations. Segregation was the legally or socially enforced separation of African Americans from whites, as well as the separation of other ethnic minorities from majority and mainstream communities. While mainly referring to the physical separation and provision of separate facilities, it can also refer to other manifestations such as prohibitions against interracial marriage, and the separation of roles within an institution. The United States Armed Forces up until 1948, black units were typically separated from white units but were still led by white officers.

Fourth Ward is one of the historic six wards of Houston, Texas, United States. The Fourth Ward is located inside the 610 Loop directly west of and adjacent to Downtown Houston. The Fourth Ward is the site of Freedmen's Town, which was a post-U.S. Civil War community of African-Americans.

The 1943Detroit race riot took place in the U.S. city of Detroit, Michigan from the evening of June 20 through to the early morning of June 22. It occurred in a period of dramatic population increase and social tensions associated with the military buildup of U.S. participation in World War II, as Detroit's automotive industry was converted to the war effort. Existing social tensions and housing shortages were exacerbated by racist feelings about the arrival of nearly 400,000 migrants, both African-American and White Southerners, from the Southeastern United States between 1941 and 1943. The new migrants competed for space and jobs, as well as against European immigrants and their descendants. The riot escalated in the city after a false rumor spread that a mob of whites had thrown a black mother and her baby into the Detroit River. Blacks looted and destroyed white property as retaliation. Whites overran Woodward to Veron where they proceeded to tip over 20 cars that belonged to black families.

Albert Eugene Cobo was an American politician who served as mayor of Detroit from 1950 to 1957.

In the United States, housing segregation is the practice of denying African Americans and other minority groups equal access to housing through the process of misinformation, denial of realty and financing services, and racial steering. Housing policy in the United States has influenced housing segregation trends throughout history. Key legislation include the National Housing Act of 1934, the G.I. Bill, and the Fair Housing Act. Factors such as socioeconomic status, spatial assimilation, and immigration contribute to perpetuating housing segregation. The effects of housing segregation include relocation, unequal living standards, and poverty. However, there have been initiatives to combat housing segregation, such as the Section 8 housing program.

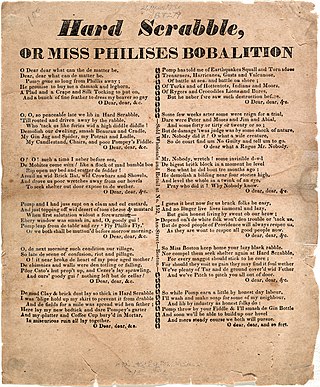

Hard Scrabble and Snow Town were two African American neighborhoods located in Providence, Rhode Island in the nineteenth century. They were also the sites of race riots in which working-class whites destroyed multiple black homes in 1824 and 1831, respectively.

The Englewood race riot, or Peoria Street riot, was one of many post-World War II race riots in Chicago, Illinois that took place in November 1949.

Lincoln Johnson Ragsdale Sr. was an influential leader in the Phoenix-area Civil Rights Movement. Known for his outspokenness, Ragsdale was instrumental in various reform efforts in the Valley, including voting rights and the desegregation of schools, neighborhoods, and public accommodations.

The history of St. Louis, Missouri from 1981 to the present has been marked by city beautification and crime prevention efforts, a major school desegregation case, and gentrification in its downtown area. St. Louis also continues to struggle with crime and a declining population, although some improvement has been made in both of these aspects.

Patterson Park is a neighborhood in Baltimore, Maryland, United States. Named for the 137-acre park that abuts its north and east sides, the neighborhood is in the southeast section of Baltimore city, roughly two miles east of Baltimore's downtown district.

Racial segregation in Atlanta has known many phases after the freeing of the slaves in 1865: a period of relative integration of businesses and residences; Jim Crow laws and official residential and de facto business segregation after the Atlanta Race Riot of 1906; blockbusting and black residential expansion starting in the 1950s; and gradual integration from the late 1960s onwards. A 2015 study conducted by Nate Silver of fivethirtyeight.com, found that Atlanta was the second most segregated city in the U.S. and the most segregated in the South.

From the mid 1960s until the late 1980s, Chicago's Marquette Park was the scene of many racially charged rallies that erupted in violence. The rallies often spilled into the residential areas surrounding the park.

Joseph Charles Jones was an American civil rights leader, attorney, co-founder of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and chairperson of the SNCC's direct action committee.

References

- ↑ William Freivogel, "Novel Trust Promotes Integration, But White Steering May Be Illegal." St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Aug. 1, 1979, p. 9A

- ↑ NiNi Harris, Legacy of Lions: a History of University City, p.156. Historical Society of University City, 1981

- ↑ Charles T. Henry, A History of Community Sustainability, p.3 Historical Society of University City, 2012

- ↑ Kay Drey, "Background Information for the Formation of the University City Home Rental Trust" n.d.p.1. Drey, Kay, Queeny Park Collection, State Historical Society of Missouri archives

- ↑ Freivogel, "Novel Trust"

- ↑ Lorenz, W.G., "A Problem--Its Solution" p. 6. 1968. Drey, Kay Queeny Park Collection

- ↑ Kay Drey, "Background Information"

- ↑ Letter from W.G. Lorenz to J. Becker, March 4, 1968. Drey, Kay Queeny Park Collection

- ↑ Minutes of the Executive Committee Meeting of the UCHRT, Sept. 1969. Drey, Kay, Queeny Park Collection

- ↑ Minutes of the Executive Committee Meeting of the UCHRT, Sept. 1969. Drey, Kay, Queeny Park Collection.

- ↑ Minutes of the Executive Committee Meeting of the UCHRT, Dec. 1969. Drey, Kay, Queeny Park Collection.

- ↑ Minutes of the Executive Committee Meeting of the UCHRT, Sept. 11, 1968. Drey, Kay, Queeny Park Collection.

- ↑ Minutes of the Executive Committee Meeting of the UCHRT, Dec. 1971. Drey, Kay, Queeny Park Collection.

- ↑ Minutes of the Executive Committee Meeting of the UCHRT, April 1969. Drey, Kay, Queeny Park Collection.

- ↑ Letter to Morris Milgram from Kay Drey, March 13, 1973. Drey, Kay, Queeny Park Collection

- ↑ letter to Gabriele Guttkind from Kay Drey, March 27, 1974. Drey, Kay, Queeny Park Collection.

- ↑ Memo to Members of the Executive Committee from Zelda Epstein, May 21, 1977. Drey, Kay, Queeny Park Collection.

- ↑ Minutes of the Executive Committee Meeting of the UCHRT, April 1970. Drey, Kay, Queeny Park Collection.

- ↑ Freivogel, "Novel Trust"

- ↑ "Helping Integration: a Suburban Dilemma." St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Aug. 26, 1979, p.6

- ↑ Minutes of Meeting of Investors, July 11, 1984. Drey, Kay, Queeny Park Collection

- ↑ Letter to Henry and Charles Lowenhaupt from Kay Drey, Oct. 19, 1985. Drey, Kay, Queeny Park Collection

- ↑ Letter to Investors and Executive Committee from Kay Drey, Dec. 18, 1990. Drey, Kay, Queeny Park Collection