The Satires are a collection of satirical poems by the Latin author Juvenal written between the end of the first and the early second centuries A.D.

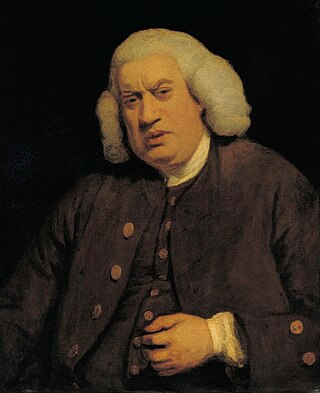

Samuel Johnson, often called Dr Johnson, was an English writer who made lasting contributions as a poet, playwright, essayist, moralist, literary critic, sermonist, biographer, editor, and lexicographer. The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography calls him "arguably the most distinguished man of letters in English history".

Robert Dodsley was an English bookseller, publisher, poet, playwright, and miscellaneous writer.

This article contains information about the literary events and publications of 1738.

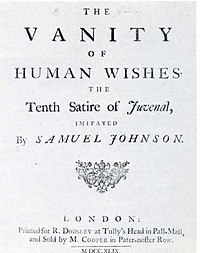

This article contains information about the literary events and publications of 1749.

The term Metaphysical poets was coined by the critic Samuel Johnson to describe a loose group of 17th-century English poets whose work was characterised by the inventive use of conceits, and by a greater emphasis on the spoken rather than lyrical quality of their verse. These poets were not formally affiliated and few were highly regarded until 20th century attention established their importance.

"Ode on a Grecian Urn" is a poem written by the English Romantic poet John Keats in May 1819, first published anonymously in Annals of the Fine Arts for 1819.

Absalom and Achitophel is a celebrated satirical poem by John Dryden, written in heroic couplets and first published in 1681. The poem tells the Biblical tale of the rebellion of Absalom against King David; in this context it is an allegory used to represent a story contemporary to Dryden, concerning King Charles II and the Exclusion Crisis (1679–1681). The poem also references the Popish Plot (1678).

In Latin literature, Augustan poetry is the poetry that flourished during the reign of Caesar Augustus as Emperor of Rome, most notably including the works of Virgil, Horace, and Ovid. In English literature, Augustan poetry is a branch of Augustan literature, and refers to the poetry of the 18th century, specifically the first half of the century. The term comes most originally from a term that George I had used for himself. He saw himself as an Augustus. Therefore, the British poets picked up that term as a way of referring to their endeavours, for it fit in another respect: 18th-century English poetry was political, satirical, and marked by the central philosophical problem of whether the individual or society took precedence as the subject of the verse.

John Oldham was an English satirical poet and translator. John Dryden, England's first Poet Laureate, was one of his admirers and upon his death wrote an elegy "To the Memory of Mr. Oldham".

Augustan literature is a style of British literature produced during the reigns of Queen Anne, King George I, and George II in the first half of the 18th century and ending in the 1740s, with the deaths of Alexander Pope and Jonathan Swift, in 1744 and 1745, respectively. It was a literary epoch that featured the rapid development of the novel, an explosion in satire, the mutation of drama from political satire into melodrama and an evolution toward poetry of personal exploration. In philosophy, it was an age increasingly dominated by empiricism, while in the writings of political economy, it marked the evolution of mercantilism as a formal philosophy, the development of capitalism and the triumph of trade.

Literature of the 18th century refers to world literature produced during the years 1700–1799.

Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard is a poem by Thomas Gray, completed in 1750 and first published in 1751. The poem's origins are unknown, but it was partly inspired by Gray's thoughts following the death of the poet Richard West in 1742. Originally titled Stanzas Wrote in a Country Church-Yard, the poem was completed when Gray was living near the Church of St Giles, Stoke Poges. It was sent to his friend Horace Walpole, who popularised the poem among London literary circles. Gray was eventually forced to publish the work on 15 February 1751 in order to preempt a magazine publisher from printing an unlicensed copy of the poem.

Nationality words link to articles with information on the nation's poetry or literature.

Decimus Junius Juvenalis, known in English as Juvenal, was a Roman poet active in the late first and early second century CE. He is the author of the collection of satirical poems known as the Satires. The details of Juvenal's life are unclear, although references within his text to known persons of the late first and early second centuries CE fix his earliest date of composition. One recent scholar argues that his first book was published in 100 or 101. A reference to a political figure dates his fifth and final surviving book to sometime after 127.

Nationality words link to articles with information on the nation's poetry or literature.

London is a poem by Samuel Johnson, produced shortly after he moved to London. Written in 1738, it was his first major published work. The poem in 263 lines imitates Juvenal's Third Satire, expressed by the character of Thales as he decides to leave London for Wales. Johnson imitated Juvenal because of his fondness for the Roman poet and he was following a popular 18th-century trend of Augustan poets headed by Alexander Pope that favoured imitations of classical poets, especially for young poets in their first ventures into published verse.

Irene is a Neoclassical tragedy written between 1726 and 1749 by Samuel Johnson. It has the distinction of being the work Johnson considered his greatest failure. Since his death, the critical consensus has been that he was right to think so.

Samuel Johnson was an English author born in Lichfield, Staffordshire. He was a sickly infant who early on began to exhibit the tics that would influence how people viewed him in his later years. From childhood he displayed great intelligence and an eagerness for learning, but his early years were dominated by his family's financial strain and his efforts to establish himself as a school teacher.

Countess Amalie Sophie Marianne von Wallmoden-Gimborn, Countess of Yarmouth, born Amalie von Wendt was the principal mistress of King George II from the mid-1730s until his death in 1760. Born into a prominent family in the Electorate of Hanover, and married into another, in 1740 she became a naturalised subject of Great Britain and was granted a peerage for life, with the title of "Countess of Yarmouth", becoming the last royal mistress to be so honoured. She remained in England until the death in 1760 of King George II, who is believed to have fathered her second son, Johann Ludwig, Reichsgraf von Wallmoden-Gimborn. She returned to Hanover for the rest of her life, surviving the king for nearly five years.