Christine de Pizan or Pisan, was an Italian-born French poet and court writer for King Charles VI of France and several French dukes.

The Book of the City of Ladies, or Le Livre de la Cité des Dames, is a book written by Christine de Pizan believed to have been finished by 1405. Perhaps Pizan's most famous literary work, it is her second work of lengthy prose. Pizan uses the vernacular French language to compose the book, but she often uses Latin-style syntax and conventions within her French prose. The book serves as her formal response to Jean de Meun's popular Roman de la Rose. Pizan combats Meun's statements about women by creating an allegorical city of ladies. She defends women by collecting a wide array of famous women throughout history. These women are "housed" in the City of Ladies, which is actually the book. As Pizan builds her city, she uses each famous woman as a building block for not only the walls and houses of the city, but also as building blocks for her thesis. Each woman introduced to the city adds to Pizan's argument towards women as valued participants in society. She also advocates in favour of education for women.

Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa von Nettesheim was a German Renaissance polymath, physician, legal scholar, soldier, knight, theologian, and occult writer. Agrippa's Three Books of Occult Philosophy published in 1533 drew heavily upon Kabbalah, Hermeticism, and neo-Platonism. His book was widely influential among esotericists of the early modern period, and was condemned as heretical by the inquisitor of Cologne.

Equality feminism is a subset of the overall feminism movement and more specifically of the liberal feminist tradition that focuses on the basic similarities between men and women, and whose ultimate goal is the equality of both genders in all domains. This includes economic and political equality, equal access within the workplace, freedom from oppressive gender stereotyping, and an androgynous worldview.

The history of feminism comprises the narratives of the movements and ideologies which have aimed at equal rights for women. While feminists around the world have differed in causes, goals, and intentions depending on time, culture, and country, most Western feminist historians assert that all movements that work to obtain women's rights should be considered feminist movements, even when they did not apply the term to themselves. Some other historians limit the term "feminist" to the modern feminist movement and its progeny, and use the label "protofeminist" to describe earlier movements.

Marie de Gournay was a French writer, who wrote a novel and a number of other literary compositions, including The Equality of Men and Women and The Ladies' Grievance. She insisted that women should be educated. Gournay was also an editor and commentator of Michel de Montaigne. After Montaigne's death, Gournay edited and published his Essays.

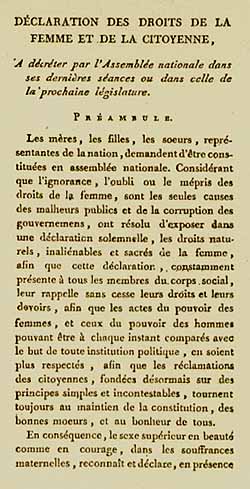

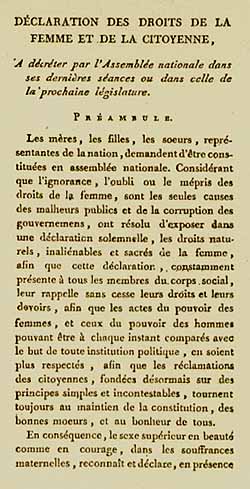

The Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Female Citizen, also known as the Declaration of the Rights of Woman, was written on 14 September 1791 by French activist, feminist, and playwright Olympe de Gouges in response to the 1789 Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen. By publishing this document on 15 September, de Gouges hoped to expose the failures of the French Revolution in the recognition of gender equality. As a result of her writings, de Gouges was accused, tried and convicted of treason, resulting in her immediate execution, along with the Girondists.

Gabrielle Suchon was a French moral philosopher who participated in debates about the social, political and religious condition of women in the early modern era. Her most prominent works are the Traité de la morale et de la politique and Du célibat volontaire.

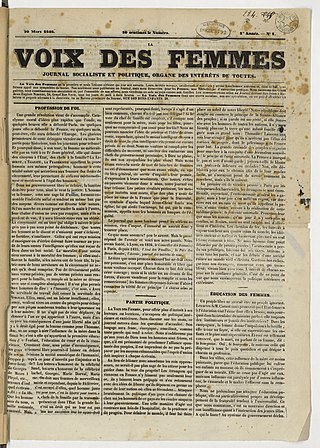

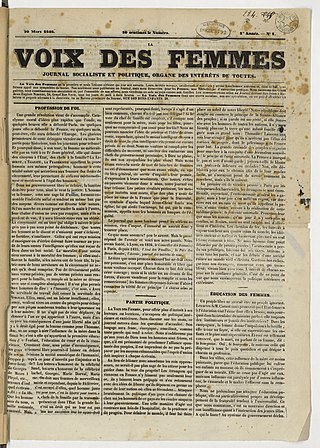

La Voix des Femmes was a French socialist feminist newspaper, founded by Eugénie Niboyet in 1848. It was the first female-led paper to be published daily in France, and grew to encompass an entire organization known as the Société de la Voix des Femmes. Some of its members included Jeanne Deroin, Suzanne Voilquin, Desirée Gay, and Amélie Pray.

Protofeminism is a concept that anticipates modern feminism in eras when the feminist concept as such was still unknown. This refers particularly to times before the 20th century, although the precise usage is disputed, as 18th-century feminism and 19th-century feminism are often subsumed into "feminism". The usefulness of the term protofeminist has been questioned by some modern scholars, as has the term postfeminist.

Jeanne Deroin was a French socialist feminist. She spent the latter half of her life in exile in London, where she continued her organising activities.

Moderata Fonte, directly translating to Modest Well, is a pseudonym of Modesta di Pozzo di Forzi, also known as Modesto Pozzo, (1555–1592) a Venetian writer and poet. Besides the posthumously-published dialogues, Giustizia delle donne and Il merito delle donne, for which she is best known, she wrote a romance and religious poetry. Details of her life are known from the biography by Giovanni Niccolò Doglioni (1548-1629), her uncle, included as a preface to the dialogue.

Feminist political theory is an area of philosophy that focuses on understanding and critiquing the way political philosophy is usually construed and on articulating how political theory might be reconstructed in a way that advances feminist concerns. Feminist political theory combines aspects of both feminist theory and political theory in order to take a feminist approach to traditional questions within political philosophy.

Lucrezia Marinella (1571-1653) was an Italian poet, author, philosopher, polemicist, and women's rights advocate. She is best known for her polemical treatise The Nobility and Excellence of Women and the Defects and Vices of Men (1600). Her works have been noted for bringing women into the philosophical and scientific community during the late Renaissance.

Bartolomeo Goggio was an Italian author and notary. He was born in Ferrara circa 1430 and died some time after 1493. He is most recognized for De laudibus mulierum [On the Merits of Women], written in the late 1480s, which was dedicated to Eleanor of Naples, Duchess of Ferrara. Only one surviving manuscript of De laudibus mulierum, held at the British Library, is known to exist. For this work, Goggio is recognized as a contributor to the pro-woman side of the querelle des femmes — "a debate about the nature and worth of women that unfolded in Europe from the medieval to the early modern period". In De laudibus mulierum Goggio argues for the superiority of women. After Eleanor's death, Goggio wrote another philosophical work, De nobilitate humani animi opus.

Agostino Strozzi was an Augustinian abbot and author. Strozzi is recognized for his contribution to the pro-woman side of the querelle des femmes — "a debate about the nature and worth of women that unfolded in Europe from the medieval to the early modern period." Strozzi, commissioned by his cousin Margherita Cantelmo, wrote La defensione delle donne [The Defense of Women] in the 16th century.

Marguerite Buffet was a French writer, grammarian, and teacher. Buffet is recognized for her contribution to the pro-woman side of the querelle des femmes – " a debate about the nature and worth of women that unfolded in Europe from the medieval to the early modern period." Her "only extant work", published in 1668, "is the Nouvelles observations sur la langue françoise, Où il est traitté des termes anciens & inusitez, & du bel usage des mots nouveaux. Avec les Éloges des Illustres Sçavantes, tant Anciennes que Modernes ".

Caroline Auguste Fischer was a German writer and women's rights activist.

Il merito delle donne, most commonly translated The Worth of Women: Wherein is Clearly Revealed Their Nobility and Their Superiority to Men, is a dialogue by Moderata Fonte first published posthumously in 1600. The work is a dialogue between seven Venetian women discussing the worth of women and the differences between the sexes more generally. The title has also been translated The Merits of Women.

"Sophia, a Person of Quality" was a pen name used by the author of two English protofeminist treatises published in the mid-18th century, following a period trend of women's histories and political tracts arguing in favor of equal rights known as the querelle des femmes. The first tract under the Sophia name, Woman Not Inferior to Man, was published in 1739. Largely adapting François Poullain de la Barre's 1676 De l'Égalité des deux sexes, Sophia expands on the text using Cartesian rhetoric to attack male superiority, with a focus on establishing the equality of women's abilities with men, as well as stating that women hold an inherent moral superiority. Following the publication in 1739 of an anonymous rebuttal tract, Man Superior to Woman, Sophia wrote a follow-up tract titled Woman's Superior Excellence Over Man. Published in 1740, the text accepts the rebuttal's challenge to prove the moral superiority of women in order to justify women's rights. All three of these tracts were later compiled and published as a single volume in 1751, entitled Beauty's Triumph.