Related Research Articles

Christopher Marlowe, also known as Kit Marlowe, was an English playwright, poet and translator of the Elizabethan era. Marlowe is among the most famous of the Elizabethan playwrights. Based upon the "many imitations" of his play Tamburlaine, modern scholars consider him to have been the foremost dramatist in London in the years just before his mysterious early death. Some scholars also believe that he greatly influenced William Shakespeare, who was baptised in the same year as Marlowe and later succeeded him as the pre-eminent Elizabethan playwright. Marlowe was the first to achieve critical reputation for his use of blank verse, which became the standard for the era. His plays are distinguished by their overreaching protagonists. Themes found within Marlowe's literary works have been noted as humanistic with realistic emotions, which some scholars find difficult to reconcile with Marlowe's "anti-intellectualism" and his catering to the prurient tastes of his Elizabethan audiences for generous displays of extreme physical violence, cruelty, and bloodshed.

The Life and Death of King Richard the Second, commonly called Richard II, is a history play by William Shakespeare believed to have been written around 1595. Based on the life of King Richard II of England, it chronicles his downfall and the machinations of his nobles. It is the first part of a tetralogy, referred to by some scholars as the Henriad, followed by three plays about Richard's successors: Henry IV, Part 1; Henry IV, Part 2; and Henry V.

The Raigne of King Edward the Third, commonly shortened to Edward III, is an Elizabethan play printed anonymously in 1596, and at least partly written by William Shakespeare. It began to be included in publications of the complete works of Shakespeare only in the late 1990s. Scholars who have supported this attribution include Jonathan Bate, Edward Capell, Eliot Slater, Eric Sams, Giorgio Melchiori and Brian Vickers. The play's co-author remains the subject of debate: suggestions have included Thomas Kyd, Christopher Marlowe, Michael Drayton, Thomas Nashe and George Peele.

Henry IV, Part 1 is a history play by William Shakespeare, believed to have been written not later than 1597. The play dramatises part of the reign of King Henry IV of England, beginning with the battle at Homildon Hill late in 1402, and ending with King Henry's victory in the Battle of Shrewsbury in mid-1403. In parallel to the political conflict between King Henry and a rebellious faction of nobles, the play depicts the escapades of King Henry's son, Prince Hal, and his eventual return to court and favour.

In the First Folio, the plays of William Shakespeare were grouped into three categories: comedies, histories, and tragedies. The histories—along with those of contemporary Renaissance playwrights—help define the genre of history plays. The Shakespearean histories are biographies of English kings of the previous four centuries and include the standalones King John, Edward III and Henry VIII as well as a continuous sequence of eight plays. These last are considered to have been composed in two cycles. The so-called first tetralogy, apparently written in the early 1590s, covers the Wars of the Roses saga and includes Henry VI, Parts I, II & III and Richard III. The second tetralogy, finished in 1599 and including Richard II, Henry IV, Parts I & II and Henry V, is frequently called the Henriad after its protagonist Prince Hal, the future Henry V.

The Shakespeare apocrypha is a group of plays and poems that have sometimes been attributed to William Shakespeare, but whose attribution is questionable for various reasons. The issue is separate from the debate on Shakespearean authorship, which addresses the authorship of the works traditionally attributed to Shakespeare.

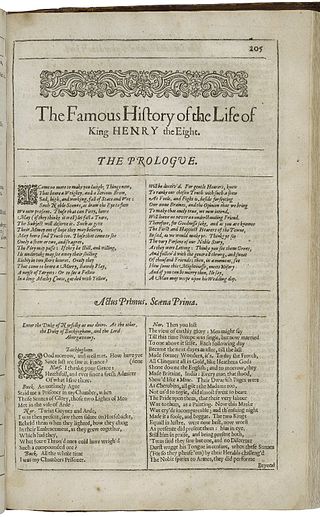

Henry VIII is a collaborative history play, written by William Shakespeare and John Fletcher, based on the life of Henry VIII. An alternative title, All Is True, is recorded in contemporary documents, with the title Henry VIII not appearing until the play's publication in the First Folio of 1623. Stylistic evidence indicates that individual scenes were written by either Shakespeare or his collaborator and successor, John Fletcher. It is also somewhat characteristic of the late romances in its structure. It is noted for having more stage directions than any of Shakespeare's other plays.

Thomas Lord Cromwell is an Elizabethan history play, depicting the life of Thomas Cromwell, 1st Earl of Essex, the minister of King Henry VIII of England.

Locrine is an Elizabethan play depicting the legendary Trojan founders of the nation of England and of Troynovant (London). The play presents a cluster of complex and unresolved problems for scholars of English Renaissance theatre.

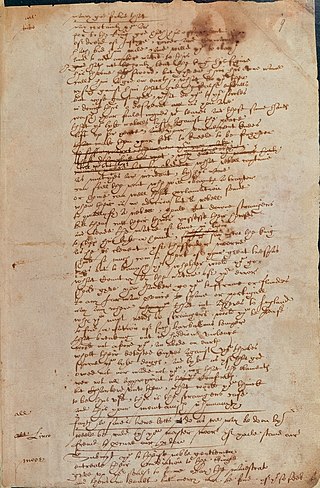

Sir Thomas More is an Elizabethan play and a dramatic biography based on particular events in the life of the Catholic martyr Thomas More, who rose to become the Lord Chancellor of England during the reign of Henry VIII. The play is considered to be written by Anthony Munday and Henry Chettle and revised by several writers. The manuscript is particularly notable for a three-page handwritten revision now widely attributed to William Shakespeare.

A Yorkshire Tragedy is an early Jacobean era stage play, a domestic tragedy printed in 1608. The play was originally assigned to William Shakespeare, though the modern critical consensus rejects this attribution, favouring Thomas Middleton.

Arden of Faversham is an Elizabethan play, entered into the Register of the Stationers Company on 3 April 1592, and printed later that same year by Edward White. It depicts the real-life murder of Thomas Arden by his wife Alice Arden and her lover, and their subsequent discovery and punishment. The play is notable as perhaps the earliest surviving example of domestic tragedy, a form of Renaissance play which dramatized recent and local crimes rather than far-off and historical events.

The Merry Devil of Edmonton is an Elizabethan-era stage play; a comedy about a magician, Peter Fabell, nicknamed the Merry Devil. It was at one point attributed to William Shakespeare, but is now considered part of the Shakespeare Apocrypha.

Like most playwrights of his period, William Shakespeare did not always write alone. A number of his surviving plays are collaborative, or were revised by others after their original composition, although the exact number is open to debate. Some of the following attributions, such as The Two Noble Kinsmen, have well-attested contemporary documentation; others, such as Titus Andronicus, are dependent on linguistic analysis by modern scholars; recent work on computer analysis of textual style has given reason to believe that parts of some of the plays ascribed to Shakespeare are actually by other writers.

Fair Em, the Miller's Daughter of Manchester, is an Elizabethan-era stage play, a comedy written c. 1590. It was bound together with Mucedorus and The Merry Devil of Edmonton in a volume labelled "Shakespeare. Vol. I" in the library of Charles II. Though scholarly opinion generally does not accept the attribution to William Shakespeare, there are a few who believe they see Shakespeare's hand in this play.

Thomas Creede was a printer of the Elizabethan and Jacobean eras, rated as "one of the best of his time." Based in London, he conducted his business under the sign of the Catherine Wheel in Thames Street from 1593 to 1600, and under the sign of the Eagle and Child in the Old Exchange from 1600 to 1617. Creede is best known for printing editions of works in English Renaissance drama, especially for ten editions of six Shakespearean plays and three works in the Shakespeare Apocrypha.

The True Tragedy of Richard III is an anonymous Elizabethan history play on the subject of Richard III of England. It has attracted the attention of scholars of English Renaissance drama principally for the question of its relationship with William Shakespeare's Richard III.

The Downfall of Robert Earl of Huntingdon and The Death of Robert Earl of Huntingdon are two closely related Elizabethan-era stage plays on the Robin Hood legend, that were written by Anthony Munday in 1598 and published in 1601. They are among the relatively few surviving examples of the popular drama acted by the Admiral's Men during the Shakespearean era.

The Famous Victories of Henry the fifth: Containing the Honourable Battel of Agin-court: As it was plaide by the Queenes Maiesties Players, is an anonymous Elizabethan play, which is generally thought to be a source for Shakespeare's Henriad. It was entered by printer Thomas Creede in the Stationers' Register in 1594, but the earliest known edition is from 1598. A second quarto was published in 1617.

Shakespeare attribution studies is the scholarly attempt to determine the authorial boundaries of the William Shakespeare canon, the extent of his possible collaborative works, and the identity of his collaborators. The studies, which began in the late 17th century, are based on the axiom that every writer has a unique, measurable style that can be discriminated from that of other writers using techniques of textual criticism originally developed for biblical and classical studies. The studies include the assessment of different types of evidence, generally classified as internal, external, and stylistic, of which all are further categorised as traditional and non-traditional.

References

- ↑ Brooke, C. F. Tucker, The Shakespeare Apocrypha Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1918; Kozlenko, William,Disputed Plays of William Shakespeare, New York: Hawthorne Publishers, 1974

- ↑ The Riverside Shakespeare at 842, 2000 (2nd ed. 1997)

- ↑ Corbin, Peter, and Douglas Sedge. (2002) Thomas of Woodstock: or, Richard II, Part One, Manchester University Press, p. 4.

- ↑ Sams, Eric. (1986). Shakespeare's Edmund Ironside: The Lost Play. Wildwood Ho. ISBN 0-7045-0547-9

- ↑ Corbin and Sedge, 2002, p. 1.

- ↑ Id. at 1–3, 38–39.

- ↑ Id. at 40

- ↑ Corbin and Sedge, 2002, pp. 3–4.

- ↑ Wilhelmina P. Frijlinck, ed. The First Part of the Reign of King Richard II or Thomas of Woodstock. Malone Society, 1929, p.v.

- ↑ A.P. Rossiter, Woodstock: A Moral History (London: Chatto & Windus, 1946), p. 26

- ↑ Frijlinck, First Part.

- ↑ Rossiter, Woodstock, p. 73

- 1 2 Macd. P. Jackson, "Shakespeare's Richard II and the Anonymous Thomas of Woodstock,", in Medieval and Renaissance Drama in England 14 (2001) 17–65. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24322987

- ↑ Corbin and Sedge, 2002, p. 4.

- ↑ Egan, Michael (2006). The Tragedy of Richard II: A Newly Authenticated Play by William Shakespeare. Edwin Mellen Press. ISBN 0-7734-6082-9.

- ↑ "Last weeks letters". The Times. London. 26 March 2008. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- ↑ Robinson, Ian, Richard II and Woodstock, Brynmill Press, 1988 Retrieved 29 November 2013

- ↑ SHAKSPER 2005: Wager

- ↑ http://shaksper.net/archive/2011/304-august/28082-thomas-of-woodstock; see, also, "Poor Richards," SHK 25.080 Sunday, 16 February 2014

- 1 2 Sams, Eric, The Real Shakespeare: Retrieving the Later Years, 1594–1616, p.342 (unfinished at the time of Sams' death, an edited text being published as an e-book by the Centro Studi "Eric Sams", 2008 )

- ↑ Frijlinck, First Part., p. xxiii

- ↑ Ule, A Concordance to the Shakespeare Apocrypha, which contains an edition of the play and a discussion of its authorship.

- ↑ Corbin and Sedge, 2002, pp. 4, 8.

- ↑ "Thomas of Woodstock: Title Page". Hampshire Shakespeare Company. Archived from the original on 30 November 2012. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- ↑ Pacific Repertory Theatre website archives

- ↑ Ehren, Christine (14 October 2001). "Lost Shakespeare Lost Again: CA Thomas of Woodstock, Edward III Ends U.S. Debut Oct. 14". Playbill. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- ↑ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine : "Thomas of Woodstock | Second Look, part 1 (Beyond Shakespeare Exploring Session)". YouTube .

There is a full chapter about this anonymous play in Kevin De Ornellas, The Horse in Early Modern English Culture, Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2013. ISBN 978-1611476583.