The history of Sudan refers to the territory that today makes up Republic of the Sudan and the state of South Sudan, which became independent in 2011. The territory of Sudan is geographically part of a larger African region, also known by the term "Sudan". The term is derived from Arabic: بلاد السودان bilād as-sūdān, or "land of the black people", and has sometimes been used more widely referring to the Sahel belt of West and Central Africa.

Makuria was a medieval Nubian kingdom in what is today northern Sudan and southern Egypt. Its capital was Dongola in the fertile Dongola Reach, and the kingdom is sometimes known by the name of its capital.

Alodia, also known as Alwa, was a medieval kingdom in what is now central and southern Sudan. Its capital was the city of Soba, located near modern-day Khartoum at the confluence of the Blue and White Nile rivers.

Old Dongola is a deserted town in what is now Northern State, Sudan, located on the east bank of the Nile opposite the Wadi Howar. An important city in medieval Nubia, and the departure point for caravans west to Darfur and Kordofan, from the fourth to the fourteenth century Old Dongola was the capital of the Makurian state. A Polish archaeological team has been excavating the town since 1964.

Georgios II was a ruler of the medieval Nubian kingdom of Makuria. He ascended the throne in 887, after the death of his father Georgios I, and ruled until 915 or 920, when he was succeeded by his son Zacharias II. Belonging to the Dynasty of Zacharias, little is known about his rule, although it is recorded that at some point between 910 and 915, his kingdom was involved in a war with the Abbasid Caliphate.

Soba is an archaeological site and former town in what is now central Sudan. Three kingdoms existed in medieval Nubia: Nobadia with the capital in Faras, Makuria with the capital in Dongola, and Alodia (Alwa) with the capital in Soba. The latter used to be the capital of the medieval Nubian kingdom of Alodia from the sixth century until around 1500. E. A. Wallis Budge identified it with a group of ruins on the Blue Nile 19 kilometres (12 mi) from Khartoum, where there are remains of a Meroitic temple that had been converted into a Christian church.

Faras was a major city in Lower Nubia. The site of the city, on the border between modern Egypt and Sudan at Wadi Halfa Salient, was flooded by Lake Nasser in the 1960s and is now permanently underwater. Before this flooding, extensive archaeological work was conducted by a Polish archaeological team led by professor Kazimierz Michałowski.

Nobatia or Nobadia was a late antique kingdom in Lower Nubia. Together with the two other Nubian kingdoms, Makuria and Alodia, it succeeded the kingdom of Kush. After its establishment in around 400, Nobadia gradually expanded by defeating the Blemmyes in the north and incorporating the territory between the second and third Nile cataract in the south. In 543, it converted to Coptic Christianity. It would then be annexed by Makuria, under unknown circumstances, during the 7th century.

The Tunjur people are a Sunni Muslim ethnic group living in eastern Chad and western Sudan. In the 21st century, their numbers have been estimated at 175,000 people.

Al-Malik al-Zahir Rukn al-Din Baybars al-Bunduqdari, commonly known as Baibars or Baybars and nicknamed Abu al-Futuh, was the fourth Mamluk sultan of Egypt and Syria, of Turkic Kipchak origin, in the Bahri dynasty, succeeding Qutuz. He was one of the commanders of the Egyptian forces that inflicted a defeat on the Seventh Crusade of King Louis IX of France. He also led the vanguard of the Egyptian army at the Battle of Ain Jalut in 1260, which marked the first substantial defeat of the Mongol army and is considered a turning point in history.

The second battle of Dongola or siege of Dongola was a military engagement between early Arab forces of the Rashidun Caliphate and the Nubian-Christian forces of the kingdom of Makuria in 652. The battle ended Muslim expansion into Nubia, establishing trade and a historic peace between the Muslim world and a Christian nation. As a result, Makuria was able to grow into a regional power that would dominate Nubia for over the next 500 years.

The kingdom of al-Abwab was a medieval Nubian monarchy in present-day central Sudan. Initially the most northerly province of Alodia, it appeared as an independent kingdom from 1276. Henceforth it was repeatedly recorded by Arabic sources in relation to the wars between its northern neighbour Makuria and the Egyptian Mamluk sultanate, where it generally sided with the latter. In 1367 it is mentioned for the last time, but based on pottery finds it has been suggested that the kingdom continued to exist until the 15th, perhaps even the 16th, century. During the reign of Funj king Amara Dunqas the region is known to have become part of the Funj sultanate.

The Dongola Reach is a reach of approximately 160 km in length stretching from the Fourth downriver to the Third Cataracts of the Nile in Upper Nubia, Sudan. Named after the Sudanese town of Dongola which dominates this part of the river, the reach was the heart of ancient Nubia.

The Bible was translated into Old Nubian during the period when Christianity was dominant in Nubia. Throughout the Middle Ages, Nubia was divided into separate kingdoms: Nobadia, Makuria and Alodia. Old Nubian may be regarded was the standard written form in all three kingdoms. Of the living Nubian languages, it is modern Nobiin which is the closest to Old Nubian and probably its direct descendant.

The Monastery in Ghazali is a medieval Christian monastery in the Bayuda Desert in northern Sudan. Probably founded by the Makurian king Merkurios in the late 7th century, it functioned until the 13th century.

The monastery of the Archangel Gabriel at Naqlun – a Coptic monastery of the Archangel Gabriel located in northern Egypt, in the Faiyum Oasis, 16 km south-east of the city of Faiyum in the Libyan Desert. Since 1986, it is investigated by a team of researchers from the Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology University of Warsaw, headed by Prof. Włodzimierz Godlewski. In 1997, the Church of St. Gabriel was restored.

Moses Georgios was ruler of the Nubian kingdom of Makuria. During his reign it is believed that the crown of Alodia was also under the control of Makuria. He is mostly known for his conflict with Saladin.

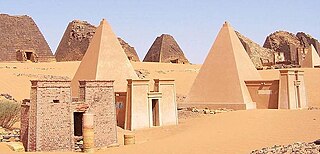

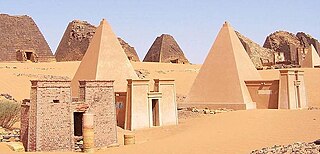

The architecture of Sudan mirrors the geographical, ethnic and cultural diversity of the country and its historical periods. The lifestyles and material culture expressed in human settlements, their architecture and economic activities have been shaped by different regional and environmental conditions. In its long documented history, Sudan has been a land of changing and diverse forms of human civilization with important influences from foreign cultures.

The Battle of Dongola (1276) was fought between the Mamluk Sultanate under Baibars and the Kingdom of Makuria. The Mamluks gained a decisive victory, capturing the Makurian capital Dongola, forcing the king David of Makuria to flee and placing a puppet on the Makurian throne. After this battle the Kingdom of Makuria went into a period of decline until its collapse in the 15th century

Gebel Adda was a mountain and archaeological site on the right bank of the Nubian Nile in what is now southern Egypt. The settlement on its crest was continuously inhabited from the late Meroitic period to the Ottoman period, when it was abandoned by the late 18th century. It reached its greatest prominence in the 14th and 15th centuries, when it seemed to have been the capital of late kingdom of Makuria. The site was superficially excavated by the American Research Center in Egypt just before being flooded by Lake Nasser in the 1960s, with much of the remaining excavated material, now stored in the Royal Ontario Museum in Canada, remaining unpublished. Unearthed were Meroitic inscriptions, Old Nubian documents, a large amount of leatherwork, two palatial structures and several churches, some of them with their paintings still intact. The nearby ancient Egyptian rock temple of Horemheb, also known as temple of Abu Oda, was rescued and relocated.