The Royal Observatory, Greenwich is an observatory situated on a hill in Greenwich Park in south east London, overlooking the River Thames to the north. It played a major role in the history of astronomy and navigation, and because the Prime Meridian passes through it, it gave its name to Greenwich Mean Time, the precursor to today's Coordinated Universal Time (UTC). The ROG has the IAU observatory code of 000, the first in the list. ROG, the National Maritime Museum, the Queen's House and the clipper ship Cutty Sark are collectively designated Royal Museums Greenwich.

The Meteorological Service of Canada is a division of Environment and Climate Change Canada, which primarily provides public meteorological information and weather forecasts and warnings of severe weather and other environmental hazards. MSC also monitors and conducts research on climate, atmospheric science, air quality, water quantities, ice and other environmental issues. MSC operates a network of radio stations throughout Canada transmitting weather and environmental information 24 hours per day called Weatheradio Canada.

Sir Edward Sabine was an Irish astronomer, geophysicist, ornithologist, explorer, soldier and the 30th president of the Royal Society.

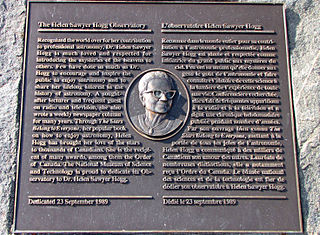

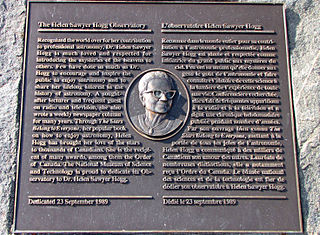

Helen Sawyer Hogg was an American-Canadian astronomer who pioneered research into globular clusters and variable stars. She was the first female president of several astronomical organizations and a notable woman of science in a time when many universities would not award scientific degrees to women. Her scientific advocacy and journalism included astronomy columns in the Toronto Star and the Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada. She was considered a "great scientist and a gracious person" over a career of sixty years.

George Ellery Hale was an American solar astronomer, best known for his discovery of magnetic fields in sunspots, and as the leader or key figure in the planning or construction of several world-leading telescopes; namely, the 40-inch refracting telescope at Yerkes Observatory, 60-inch Hale reflecting telescope at Mount Wilson Observatory, 100-inch Hooker reflecting telescope at Mount Wilson, and the 200-inch Hale reflecting telescope at Palomar Observatory. He also played a key role in the foundation of the International Union for Cooperation in Solar Research and the National Research Council, and in developing the California Institute of Technology into a leading research university.

The David Dunlap Observatory (DDO) is an astronomical observatory site in Richmond Hill, Ontario, Canada. Established in 1935, it was owned and operated by the University of Toronto until 2008. It was then acquired by the city of Richmond Hill, which provides a combination of heritage preservation, unique recreation opportunities and a celebration of the astronomical history of the site. Its primary instrument is a 74-inch (1.88 m) reflector telescope, at one time the second-largest telescope in the world, and still the largest in Canada. Several other telescopes are also located at the site, which formerly also included a small radio telescope. The scientific legacy of the David Dunlap Observatory continues in the Dunlap Institute for Astronomy & Astrophysics, a research institute at the University of Toronto established in 2008.

Armagh Observatory is an astronomical research institute in Armagh, Northern Ireland. Around 25 astronomers are based at the observatory, studying stellar astrophysics, the Sun, Solar System astronomy and Earth's climate.

The Astronomical Observatory of Modra, also known as Modra Observatory or the Astronomical and Geophysical observatory in Modra, is an astronomical observatory located in Modra, Slovakia. It is owned and operated by the Comenius University in Bratislava. The scientific research at the observatory is led by the Department of Astronomy, Physics of the Earth and Meteorology, Faculty of Mathematics, Physics and Informatics.

The Allan I. Carswell Astronomical Observatory, formerly known as the York University Astronomical Observatory, is an astronomical observatory owned and operated by York University. It is located in the North York district of Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Opened in 1969, York's observatory is opened to both researchers and amateur astronomers. The observatory was renamed the Allan Ian Carswell Astronomical Observatory in 2017 after York University Emeritus Professor of Physics Allan Carswell.

The Yale University Observatory, also known as the Leitner Family Observatory and Planetarium, is an astronomical observatory owned and operated by Yale University, and maintained for student use. It is located in Farnham Memorial Gardens near the corner of Edwards and Prospect Streets, New Haven, Connecticut.

The Royal Astronomical Society of Canada (RASC) is a national, non-profit, charitable organization devoted to the advancement of astronomy and related sciences. At present, there are 28 local branches of the Society, called Centres, in towns and cities across the country from St. John's, Newfoundland, to Victoria, British Columbia, and as far north as Whitehorse, Yukon. There are about 5100 members from coast to coast to coast, and internationally. The membership is composed primarily of amateur astronomers and also includes numerous professional astronomers and astronomy educators. The RASC is the Canadian equivalent of the British Astronomical Association.

The Royal Observatory of Belgium, has been situated in the Uccle municipality of Brussels (Belgium) since 1890. It was first established in Saint-Josse-ten-Noode in 1826 by William I under the impulse of Adolphe Quetelet. It was home to a 100 cm (39 in) diameter aperture Zeiss reflector in the first half of the 20th century, one of the largest telescopes in the world at the time. It owns a variety of other astronomical instruments, such as astrographs, as well as a range of seismograph equipment.

The Algonquin Radio Observatory (ARO) is a radio observatory located in Algonquin Provincial Park in Ontario, Canada. It opened in 1959 in order to host a number of the National Research Council of Canada's (NRC) ongoing experiments in a more radio-quiet location than Ottawa.

Arthur Edwin Covington was a Canadian physicist who made the first radio astronomy measurements in Canada. Through these he made the valuable discovery that sunspots generate large amounts of microwaves at the 10.7 cm wavelength, offering a simple all-weather method to measure and predict sunspot activity, and their associated effects on communications. The sunspot detection program has run continuously to this day.

The King's Observatory is a Grade I listed building in Richmond, London. Now a private dwelling, it formerly housed an astronomical and terrestrial magnetic observatory founded by King George III. The architect was Sir William Chambers; his design of the King's Observatory influenced the architecture of two Irish observatories – Armagh Observatory and Dunsink Observatory near Dublin.

The Stonyhurst Observatory is a functioning observatory and weather station at Stonyhurst College in Lancashire, England. Built in 1866, it replaced a nearby earlier building, built in 1838, which is now used as the Typographia Collegii.

The William Brydone Jack Observatory is a small astronomical observatory on the campus of the University of New Brunswick in Fredericton, New Brunswick. Constructed in 1851, it was the first astronomical observatory built in British North America. The observatory was designated a National Historic Site of Canada in 1954.

Lieutenant-General Charles Wright Younghusband CB FRS was a British Army officer and meteorologist.

The Royal Observatory, Cape of Good Hope, is the oldest continuously existing scientific institution in South Africa. Founded by the British Board of Longitude in 1820, it now forms the headquarters building of the South African Astronomical Observatory.

The Greenwich 28-inch refractor is a telescope at the Royal Observatory, Greenwich, where it was first installed in 1893. It is a 28-inch ( 71 cm) aperture objective lens telescope, otherwise known as a refractor, and was made by the telescope maker Sir Howard Grubb. The achromatic lens was made Grubb from Chance Brothers glass. The mounting is older however and dates to the 1850s, having been designed by Royal Observatory director George Airy and the firm Ransomes and Simms. The telescope is noted for its spherical dome which extends beyond the tower, nicknamed the "onion" dome. Another name for this telescope is "The Great Equatorial" which it shares with the building, which housed an older but smaller telescope previously.