The Muckleshoot are a Lushootseed-speaking Native American tribe, part of the Coast Salish peoples of the Pacific Northwest. They are descendants of the Duwamish peoples whose traditional territory was located along the Green and White rivers, including up to the headwaters in the foothills of the Cascade Mountains, in present-day Washington State. Since the mid-19th century, their reservation is located in the area of Auburn, Washington, about 15 miles (24 km) northeast of Tacoma and 35 miles (55 km) southeast of Seattle.

Chief Seattle was a Suquamish and Duwamish chief. A leading figure among his people, he pursued a path of accommodation to white settlers, forming a personal relationship with "Doc" Maynard. The city of Seattle, in the U.S. state of Washington, was named after him. A widely publicized speech arguing in favor of ecological responsibility and respect of Native Americans' land rights had been attributed to him.

The Tulalip Tribes of Washington, formerly known as the Tulalip Tribes of the Tulalip Reservation, is a federally recognized tribe of Duwamish, Snohomish, Snoqualmie, Skagit, Suiattle, Samish, and Stillaguamish people. They are South and Central Coast Salish peoples of indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast. Their tribes are located in the mid-Puget Sound region of Washington.

The Suquamish are a Lushootseed-speaking Native American people, located in present-day Washington in the United States. They are a southern Coast Salish people.

The Duwamish are a Lushootseed-speaking Coast Salish people in western Washington, and the Indigenous people of metropolitan Seattle.

Two conflicting perspectives exist for the early history of Seattle. There is the "establishment" view, which favors the centrality of the Denny Party, and Henry Yesler. A second, less didactic view, advanced particularly by historian Bill Speidel and others such as Murray Morgan, sees David Swinson "Doc" Maynard as a key figure, perhaps the key figure. In the late nineteenth century, when Seattle had become a thriving town, several members of the Denny Party still survived; they and many of their descendants were in local positions of power and influence. Maynard was about ten years older and died relatively young, so he was not around to make his own case. The Denny Party were generally conservative Methodists, teetotalers, Whigs and Republicans, while Maynard was a drinker and a Democrat. He felt that well-run prostitution could be a healthy part of a city's economy. He was also on friendly terms with the region's Native Americans, while many of the Denny Party were not. Thus Maynard was not on the best of terms with what became the Seattle Establishment, especially after the Puget Sound War. He was nearly written out of the city's history until Morgan's 1951 book Skid Road and Speidel's research in the 1960s and 1970s.

Alki Point is a point jutting into Puget Sound, the westernmost landform in the West Seattle district of Seattle, Washington. Alki is the peninsular neighborhood on Alki Point. Alki was the original settlement in what was to become the city of Seattle. It was part of the city of West Seattle from 1902 until that city's annexation by Seattle in 1907.

The Treaty with the Kalapuya, etc., also known as the Kalapuya Treaty or the Treaty of Dayton, was an 1855 treaty between the United States and the bands of the Kalapuya tribe, the Molala tribe, the Clackamas, and several others in the Oregon Territory. In it the tribes were forced to cede land in exchange for promised permanent reservation, annuities, supplies, educational, vocational, health services, and protection from ongoing violence from American settlers. The treaty effectively gave over the entirety of the Willamette Valley to the United States and removed indigenous groups who had resided in the area for over 10,000 years. The treaty was signed on January 22, 1855, in Dayton, Oregon, ratified on March 3, 1855, and proclaimed on April 10, 1855.

The Chimakum, also spelled Chemakum and Chimacum Native American people, were a group of Native Americans who lived in the northeastern portion of the Olympic Peninsula in Washington state, between Hood Canal and Discovery Bay until their virtual extinction in 1902. Their primary settlements were on Port Townsend Bay, on the Quimper Peninsula, and Port Ludlow Bay to the south.

The Suquamish Indian Tribe of the Port Madison Reservation is a federally recognized tribe and Indian reservation in the U.S. state of Washington.

Princess Angeline, also known in Lushootseed as Kikisoblu, Kick-is-om-lo, or Wewick, was the eldest daughter of Chief Seattle.

The Old Man House was the largest winter longhouse in what is now the U.S. state of Washington, once standing on the shore of Puget Sound. It was the center of the Suquamish village of dxʷsəq̓ʷəb on Agate Pass, just south of the present-day town of Suquamish. At one time, it was home to the famous Suquamish chiefs Kitsap and Seattle.

The Sammamish people are a Lushootseed-speaking Southern Coast Salish people. They are indigenous to the Sammamish River Valley in central King County, Washington. The Sammamish speak Lushootseed, a Coast Salish language which was historically spoken across most of Puget Sound, although its usage today is mostly reserved for cultural and ceremonial practices.

The Treaty of Point Elliott of 1855, or the Point Elliott Treaty,—also known as the Treaty of Point Elliot / Point Elliot Treaty—is the lands settlement treaty between the United States government and the Native American tribes of the greater Puget Sound region in the recently formed Washington Territory, one of about thirteen treaties between the U.S. and Native Nations in what is now Washington. The treaty was signed on January 22, 1855, at Muckl-te-oh or Point Elliott, now Mukilteo, Washington, and ratified 8 March and 11 April 1859. Between the signing of the treaty and the ratification, fighting continued throughout the region. Lands were being occupied by European-Americans since settlement in what became Washington Territory began in earnest from about 1845.

Cheshiahud and his family on Lake Union, Seattle, Washington in the 1880s are, along with Princess Angeline, among the few late-19th century Dkhw'Duw'Absh about whom a little is known. In the University of Washington (UW) Library image archives, he is called Chudups John or Lake Union John. His family were among the few of the Duwamish people who did not move from Seattle to the Port Madison Reservation or other reservations. They lived on Portage Bay, part of Lake Union, when a photo was taken around 1885. According to the Duwamish Tribe, Lake John had a cabin and potato patch at the foot of Shelby Street. A commemorative plaque of unknown reliability is said to exist at the eastern foot of Shelby. This land was given to him by Seattle pioneer David Denny or the property was purchased—see below. Photographer Orion O. Denny recorded Old Tom and Madeline, ca. 1904, further noted in the UW Library archives as Madeline and Old John, also known as Indian John or Cheshishon, who had a house on Portage Bay in the 1900s, south of what is now the UW campus although native people had been prohibited from residence in Seattle since the mid-1860s.

The region now known as Seattle has been inhabited since the end of the last glacial period. Archaeological excavations at West Point in Discovery Park, Magnolia confirm that the Seattle area has been inhabited by humans for at least 4,000 years and probably much longer. West Point was called Oka-dz-elt-cu, Per-co-dus-chule, or Pka-dzEltcu. The village of tohl-AHL-too had been inhabited at least since the 6th century CE, as had hah-AH-poos—"where there are horse clams"—at the then-mouth of the Duwamish River in what is now the Industrial District. The Lushootseed (Skagit-Nisqually)-speaking Salish Dkhw'Duw'Absh and Xacuabš —ancestors of today's Duwamish Tribe—occupied at least 17 villages in the mid-1850s and lived in some 93 permanent longhouses (khwaac'ál'al) along the lower Duwamish River, Elliott Bay, Salmon Bay, Portage Bay, Lake Washington, Lake Sammamish, and the Duwamish River tributaries, the Black and Cedar Rivers.

The Battle of Seattle was a January 26, 1856 attack by Native American tribesmen upon Seattle, Washington. At the time, Seattle was a settlement in the Washington Territory that had recently named itself after Chief Seattle (Sealth), a leader of the Suquamish and Duwamish peoples of central Puget Sound.

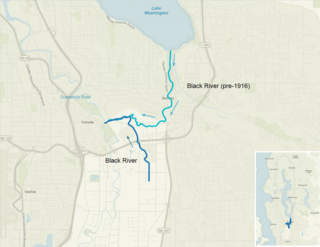

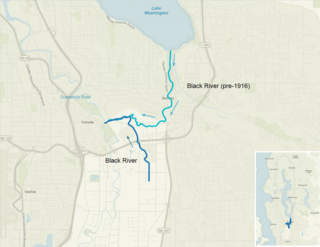

The Black River is a tributary of the Duwamish River in King County in the U.S. state of Washington. It drained Lake Washington until 1916, when the opening of the Lake Washington Ship Canal lowered the lake, causing part of the Black River to dry up. It still exists as a dammed stream about 2 miles (3.2 km) long.

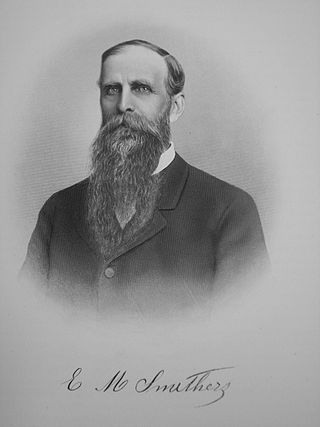

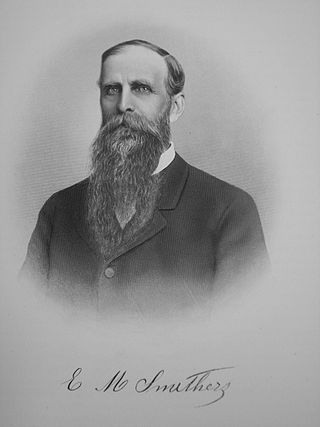

Erasmus M. Smithers was one of the European pioneers of the Pacific coast and the founder of the city of Renton, King County, Washington. His wife and her first husband had settled on the land where the town is now located in 1853, fifteen miles (24 km) from what is now Seattle. At the time there were no white settlers at a point nearer than Seattle, which was then a frontier settlement.

The Suquamish Museum preserves and displays relics and records related to the Suquamish Tribe, including artifacts from the Old Man House and the Baba'kwob site. It is located on the Port Madison Indian Reservation in Washington state and was founded in 1983. The museum currently occupies a facility opened in 2012.