During the Spanish Golden Age a great number of translations were made, specially from Arabic, Latin and Greek classics, into Spanish, and in turn, from Spanish into other languages.

During the Spanish Golden Age a great number of translations were made, specially from Arabic, Latin and Greek classics, into Spanish, and in turn, from Spanish into other languages.

The Spanish Golden Age that expanded from the late 15th century to the 17th, witnessed the flourishing of cultural and artistic expressions. Many translation of works from Latin and Greek was published and spread out throughout the rest of the Europe. At the same time, the interest for ancient Arabic scientific and medical writings was still very prominent, in spite of the fact that a large part of the Muslim community who had refused to convert to Christianity, had been expelled from Spain along with similarly unconverted Jews during the year of 1492.

The legacy from the prestigious Toledo School of Translators, established during the 12th and 13th centuries, had diminished considerably after the expulsion of the Moors and Jews from Spain in 1492, but in many of the old Arab quarters of Spanish cities the tradition of translation from Arabic to Latin or Spanish continued, although frequently in disguise to avoid the suspicions of the Inquisition. A known Spanish translation of the Muslim Koran, was made in 1456, but however, after 1492 the situation of the Muslim community left in Spain changed drastically, when they were told to accept the Christian faith by means of baptism as a condition for remaining in Spain.

Those Muslims and Jews who chose to stay in Spain while maintaining their religion had to carry out their non-Christian rituals in secret. Their religious books also had to be kept hidden, and for many years they would use Aljamiado manuscripts, which used the Arabic alphabet for transcribing Romance languages such as Mozarabic, Spanish or Ladino. Aljamiado played a very important role in preserving some of the Moriscos Islamic beliefs and traditions secretly. However, as the years passed they grew increasingly unable to read the original texts, and turned more and more to Spanish translations. Even though many of these translations were destroyed by the Inquisition, some have survived, and bear witness to the laborious task of translating and then copying the religious books by hand. In the year 1606, a Morisco copier of the Koran in Spain made this marginal notation in a mixture of Castilian, Aljamiado and Arabic:

"Esta eskrito en letra de kristyanos ... rruega y suplica que por estar en dicha letra no lo tengan en menos de lo kes, antes en mucho; porque pues esta asi declarado, esta mas a vista de los muçlimes que saben leer el cristiano y no la letra de los muçlimes. Porque es cierto que dixo el annabî Muhammad que la mejor lengwa era la ke se entendía." Translation of the passage: "It is written in the letters of the Christians: (the writer) begs that on account of being in those letters it not be belittled, but rather respected; because, being set down in this way, it can better be seen by those Muslims who know how to read Christian, but not Muslim, letters. For it is true that the Prophet Muhammad said that the best language was the one that could be understood." [1]

Nonetheless the successive Catholic monarchs were very keen on education, and created many universities and study centers, where translations took place. Besides the study and translation of philosophical and scientific works from Arabic, Greek, Hebrew and other languages from Europe and the Mediterranean basin, translations were made from literature works and orally transmuted legends and traditions from native languages in the New World.

The particular aspects of Spanish Humanism in the Renaissance did much to shape the Spanish attitude towards literary translation. In this period the English language acquired a great number of Spanish words. English lexicographers began to accumulate lists of Spanish words, beginning with John Thorius in 1590, and for the next two centuries this interest for the Spanish language facilitated translation into the two languages as well as the mutual borrowing of words.

In the New World, translations were made specially of those books deemed appropriate for the propagation of the Christian Doctrine in far away lands, predominantly in America and Asia.

Most of the issues that arose from undertaking such enormous and varied amount of translations during this period are reflected in the Don Quijote de la Mancha of Miguel de Cervantes, where he attributes the authorship of his book to a variety of characters and translators, some with Moorish names, some Spanish, and some from other parts of Europe. Cervantes also expresses his opinion on the translation process, offering a rather despairing metaphor for the end result of translations, which is frequently cited by contemporary theoreticians and translating experts:

Pero con todo eso, me parece que el traducir de una lengua en otra, como no sea de las reinas de las lenguas, griega y latina, es como quien mira los tapices flamencos por el revés: que aunque se veen las figuras, son llenas de hilos que las escurecen, y no se veen con la lisura y tez de la haz. [2]

According to Cervantes, translations (with the exception of those made between Greek and Latin), are like looking at Flemish tapestry by its reverse side, where although the main figures can be discerned, they are obscured by the loose threads and lack the clarity of the front side.

Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra was a Spanish writer widely regarded as the greatest writer in the Spanish language, and one of the world's pre-eminent novelists. He is best known for his novel Don Quixote, a work often cited as both the first modern novel, and one of the pinnacles of literature.

There are two names given in Spanish to the Spanish language: español ("Spanish") and castellano ("Castilian"). Spanish speakers from different countries or backgrounds can show a preference for one term or the other, or use them indiscriminately, but political issues or common usage might lead speakers to prefer one term over the other. This article identifies the differences between those terms, the countries or backgrounds that show a preference for one or the other, and the implications the choice of words might have for a native Spanish speaker.

Moriscos were former Muslims and their descendants whom the Roman Catholic church and the Spanish Crown obliged, under threat of death, to convert to Christianity or self-exile after Spain outlawed the open practice of Islam by its sizeable Muslim population in the early 16th century.

Aljamiado or Aljamía texts are manuscripts that use the Arabic script for transcribing European languages, especially Romance languages such as Mozarabic, Portuguese, Spanish or Ladino, and Bosnian with its Arebica script.

Spaniards, or Spanish people, are a Romance nation native to Spain. Within Spain, there are a number of National and regional ethnic identities that reflect the country's complex history and diverse cultures, including a number of different languages, among which Spanish is the majority language and the only one that is official throughout the whole country.

An Arabist is someone normally from outside the Arab world who specialises in the study of the Arabic language and culture.

Pedro Rodríguez de Campomanes y Pérez, 1st Count of Campomanes, was a Spanish statesman, economist, and writer who was Minister of the Treasury in 1760. He was an adherent of the position that the state held supremacy over the Church, often called Erastianism. Campomanes was part of the government of Spanish Bourbon monarch, Charles III.

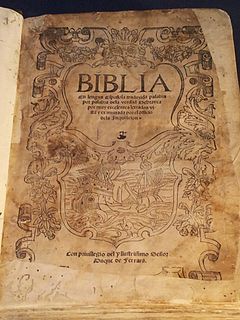

The Ferrara Bible was a 1553 publication of the Ladino version of the Tanakh used by Sephardi Jews. It was paid for and made by Yom-Tob ben Levi Athias and Abraham ben Salomon Usque, and was dedicated to Ercole II d'Este, Duke of Ferrara. Ercole's wife Renée of France was a Protestant, daughter of Louis XII of France.

Cide Hamete Benengeli is a fictional Arab Muslim historian created by Miguel de Cervantes in his novel Don Quixote, who Cervantes says is the true author of most of the work. This is a skillful metafictional literary pirouette that seems to give more credibility to the text, making believe that Don Quixote was a real person and the story is decades old. However, it's fairly obvious to the reader that such a thing is impossible, and that the pretense of Cide Hamete's work is meant as a joke.

The Toledo School of Translators is the group of scholars who worked together in the city of Toledo during the 12th and 13th centuries, to translate many of the philosophical and scientific works from Classical Arabic.

Ricote is a fictional character who is referred to in Miguel de Cervantes' novel Don Quixote. He was a wealthy Morisco shopkeeper and old friend of Sancho Panza, who was banned from Spain in 1609 like all Moriscos. The expulsion of the Moriscos was a highly topical issue at the time when Don Quixote was written - occurring in between the publication of the first part (1605) and the second one (1615).

Martí de Riquer i Morera, 8th Count of Casa Dávalos was a Spanish–Catalan literary historian and Romance philologist, a recognised international authority in the field. His writing career lasted from 1934 to 2004. He was also a nobleman and Grandee of Spain.

The Lead Books of Sacromonte are a series of texts inscribed on circular lead leaves, now considered to be 16th century forgeries.

Juan Arañés was a Spanish baroque composer. His tonos and villancicos follow the style of those preserved in the Cancionero of Kraków.

Valencians are the native people of the Valencian Community, in eastern Spain. Legally, Valencians are the inhabitants of the community. Since 2006, the Valencian people is officially recognised in the Valencian Statute of Autonomy as a "historical nation" "within the unity of the Spanish nation". The official languages of Valencia are Valencian and Spanish.

Aurelio Espinosa Pólit was an Ecuadorian writer, poet, literary critic, and university professor. He co-founded the Pontifical Catholic University of Ecuador, and he founded the Aurelio Espinosa Polit Museum and Library in Quito.

Diego Suárez Corvín, also known as Diego Suárez Montañés or el Montañés was a Spanish soldier and writer. His chronicles of the battles fought by the governor of Oran, Galcerán Borja, against the Muslims in defense of Oran have interest in that the facts are contemporary with the imprisonment of Miguel de Cervantes in Algiers.

The Young Man of Arévalo was a Morisco crypto-Muslim author from Arévalo, Castile who was the most productive known Islamic author in Spain during the period after the forced conversion of Muslims there. He traveled widely across Spain to visit crypto-Muslim communities and wrote several works about Islam which includes accounts from his travels. His real identity and dates of birth and death are unknown, but most of his travels took place in the first half of the sixteenth century.

Jean Canavaggio is a French biographer and former emeritus professor of Spanish literature at the Paris West University Nanterre La Défense.

Anagrama is a Spanish publisher founded in 1969 by Jorge Herralde. In 2010 it was sold to the Italian publisher Feltrinelli.