Seminole County is a county located in the southwestern corner of U.S. state of Georgia. As of the 2020 census, the population was 9,147. The county seat is Donalsonville.

Forsyth County is a county in the Northeast portion of the U.S. state of Georgia. Suburban and exurban in character, Forsyth County lies within the Atlanta Metropolitan Area. The county's only incorporated city and county seat is Cumming. At the 2020 census, the population was 251,283. Forsyth was the fastest-growing county in Georgia and the 15th fastest-growing county in the United States between 2010 and 2019.

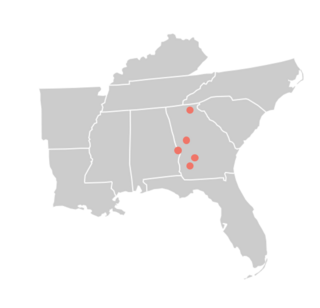

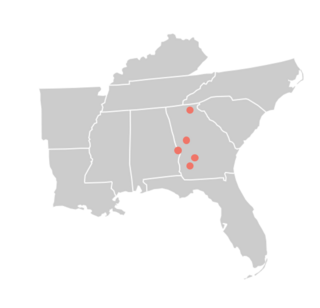

The Chattahoochee River forms the southern half of the Alabama and Georgia border, as well as a portion of the Florida and Georgia border. It is a tributary of the Apalachicola River, a relatively short river formed by the confluence of the Chattahoochee and Flint rivers and emptying from Florida into Apalachicola Bay in the Gulf of Mexico. The Chattahoochee River is about 430 miles (690 km) long. The Chattahoochee, Flint, and Apalachicola rivers together make up the Apalachicola–Chattahoochee–Flint River Basin. The Chattahoochee makes up the largest part of the ACF's drainage basin.

The Apalachicola-Chattahoochee-Flint River Basin is the drainage basin, or watershed, of the Apalachicola River, Chattahoochee River, and Flint River, in the Southeastern United States.

The Apalachicola River is a river, approximately 160 miles (260 km) long, in the state of Florida. The river's large watershed, known as the Apalachicola, Chattahoochee and Flint (ACF) River Basin, drains an area of approximately 19,500 square miles (50,500 km2) into the Gulf of Mexico. The distance to its farthest head waters in northeast Georgia is approximately 500 miles (800 km). Its name comes from Apalachicola Province, an association of Native American towns located on what is now the Chattahoochee River. The Spanish included what is now called the Chattahoochee River as part of one river, calling all of it from its origins in the southern Appalachian foothills down to the Gulf of Mexico the Apalachicola.

The Flint River is a 344-mile-long (554 km) river in the U.S. state of Georgia. The river drains 8,460 square miles (21,900 km2) of western Georgia, flowing south from the upper Piedmont region south of Atlanta to the wetlands of the Gulf Coastal Plain in the southwestern corner of the state. Along with the Apalachicola and the Chattahoochee rivers, it forms part of the ACF basin. In its upper course through the red hills of the Piedmont, it is considered especially scenic, flowing unimpeded for over 200 miles (320 km). Historically, it was also called the Thronateeska River.

Lake Lanier is a reservoir in the northern portion of the U.S. state of Georgia. It was created by the completion of Buford Dam on the Chattahoochee River in 1956, and is also fed by the waters of the Chestatee River. The lake encompasses 38,000 acres (150 km2) or 59 sq mi (150 km2) of water, and 692 mi (1,114 km) of shoreline at normal level, a "full pool" of 1,071 ft (326 m) above mean sea level and the exact shoreline varies by resolution according to the coastline paradox. Named for poet Sidney Lanier, it was built and is operated by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers for flood control and water supplies. Its construction destroyed more than 50,000 acres (20,000 ha) of farmland and displaced more than 250 families, 15 businesses, and relocated 20 cemeteries along with their remains in the process.

Apalachicola Bay is an estuary and lagoon located on the northwest coast of the U.S. state of Florida. The Apalachicola Bay system also includes St. George Sound, St. Vincent Sound and East Bay, covering an area of about 208 square miles (540 km2). Four islands, St. Vincent Island to the west, Cape St. George Island and St. George Island to the south, and Dog Island to the east, separate the system from the Gulf of Mexico. Water exchange occurs through Indian Pass, West Pass, East Pass and the Duer Channel. The lagoon has been designated as a National Estuarine Research Reserve and the Apalachicola River is the largest source of freshwater to the estuary. Combined with the Chattahoochee River, Flint River, and Ochlockonee River they drain a watershed of over 20,000 square miles (50,000 km2) at a rate of 19,599 cubic feet per second according to the United States Geological Survey in 2002.

Chattahoochee Riverkeeper (CRK) -- formerly known as Upper Chattahoochee Riverkeeper (UCR) -- is an environmental advocacy organization with 10,000 members dedicated solely to protecting and restoring the Chattahoochee River Basin. CRK was modeled after New York’s Hudson Riverkeeper and was the 11th licensed program in the international Waterkeeper Alliance. In 2012, the organization officially changed its name to simply Chattahoochee Riverkeeper (CRK), dropping the "Upper" to better reflect its stewardship over the entire river basin.

Lake Seminole is a reservoir located in the southwest corner of Georgia along its border with Florida, maintained by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. The Chattahoochee and Flint rivers join in the lake, before flowing from the Jim Woodruff Lock and Dam, which impounds the lake, as the Apalachicola River. The lake contains 37,500 acres (152 km2) of water, and has a shoreline of 376 mi (605 km). The fish in Lake Seminole include largemouth bass, crappie, chain pickerel, catfish, striped bass and other species. American alligators, snakes and various waterfowl are also present in the lake, which is known for its goose hunting.

Medionidus penicillatus, the gulf moccasinshell, is a rare species of freshwater mussel in the family Unionidae, the river mussels. This aquatic bivalve mollusk is native to Alabama, Florida, and Georgia in the United States, where it is in decline and has been extirpated from most of the rivers it once inhabited. It is a federally listed endangered species of the United States.

Northeast Georgia is a region of Georgia in the United States. The northern part is also in the north Georgia mountains, while the southern part is still hilly but much flatter in topography. Northeast Georgia is also served by the Asheville/Spartanburg/Greenville/Anderson market.

According to the Natural Resources Defense Council's recent study, Florida is one of 14 states predicted to face "high risk" water shortages by the year 2050. The state's water is primarily drawn from the Floridan Aquifer as well as from the St. Johns River, the Suwannee River, and the Ocklawaha River. Florida's regional water conflicts stem primarily from the fact that the majority of the fresh water supply is found in the rural north, while the bulk of the population, and therefore water consumption, resides in the south. Metropolitan municipalities in central and south Florida have neared their aquifer extraction limit of 650 million US gallons (2,500,000 m3) per day, leading to the search for new, extra-regional sources.

War over Water usually means Water conflict. It may also refer to the following:

Limestone Creek is a stream in Georgia, and is a tributary of the Chattahoochee River. The creek is approximately 2.32 miles (3.73 km) long.

Flat Creek is a stream in Georgia, and is a tributary of the Chattahoochee River in Lake Lanier. The creek is approximately 5.09 miles (8.19 km) long.

The Halloween darter is a small freshwater fish native to North America. It is found in Georgia and Alabama in the drainage basin of the Apalachicola River, specifically in the Flint River system and the Chattahoochee River system. It prefers shallow, fast-flowing areas with gravel bottoms in small and medium-sized rivers. It was first described in 2008, having not previously been distinguished from the Blackbanded darter (P. nigrofasciata), formerly though to occur in the same watershed. Blackbanded darter has since been split again with Westfall's darter now recognised from the Apalachicola drainage. The species is somewhat variable, being generally blackish dorsally, with some individuals having indistinct saddle-like barring. Males have orange and dark lateral striping while females have dark stripes and a yellowish-green belly. At a maximum standard length of 101 mm (4 in), males are slightly larger than females, and both sexes develop distinctive orange barring on the edge of the first dorsal fin during the breeding season.

Florida v. Georgia, 585 U.S. ___ (2018), was a decision by the Supreme Court of the United States in an original jurisdiction case. It involves a long-running dispute over waters within the ACF River Basin, running from the north Georgia mountains through metro Atlanta to the Florida panhandle, which is managed by the United States Army Corps of Engineers. Waters in the area have been stressed by the population growth of Atlanta over previous decades. The immediate case stemmed from droughts in 2011 and 2012 that caused economic damage to Florida due to lower water flows from the ACF River Basin into the panhandle, impacting its seafood production; Florida sought relief to have more water allocated towards them from the ACF by placing a water allocation cap on Georgia. The Supreme Court assigned a special master to review Florida's complaint, but ultimately found in 2016 that Florida had not fully demonstrated the need for more allocation. Florida challenged this determination to the Supreme Court. On June 27, 2018, the Supreme Court ruled 5–4 that the special master had not properly considered Florida's argument and remanded the case to be reheard and reviewed.

West Point Lake is a man-made reservoir located mostly in west-central Georgia on the Chattahoochee River and maintained by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE). The Chattahoochee river flows in from the north, before flowing through the West Point Dam, which impounds the lake, and continuing to Columbus, Georgia. Of the four major USACE lakes in the ACF River Basin, West Point Lake is the smallest by area containing 25,864 acres (10,467 ha) of water, and has the second shortest shoreline at 604 mi (972 km). The purposes of the reservoir are to provide flood control, hydroelectric power, and water storage to aid the navigation of the lower Chattahoochee.

Buford Dam is a dam in Buford, Georgia which is located at the southern end of Lake Lanier, a reservoir formed by the construction of the dam in 1956. The dam itself is managed by the United States Army Corps of Engineers.