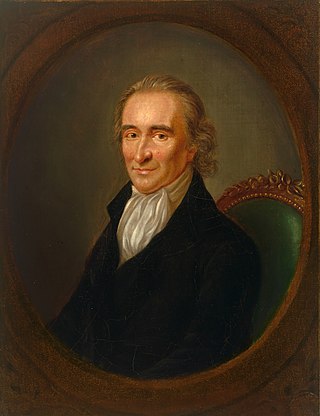

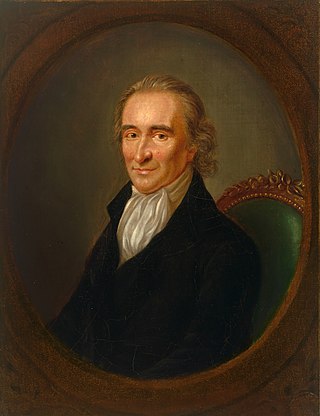

Thomas Paine was an English-born American Founding Father, French Revolutionary, political activist, philosopher, political theorist, and revolutionary. He authored Common Sense (1776) and The American Crisis (1776–1783), two of the most influential pamphlets at the start of the American Revolution, and he helped to inspire the Patriots in 1776 to declare independence from Great Britain. His ideas reflected Enlightenment-era ideals of human rights.

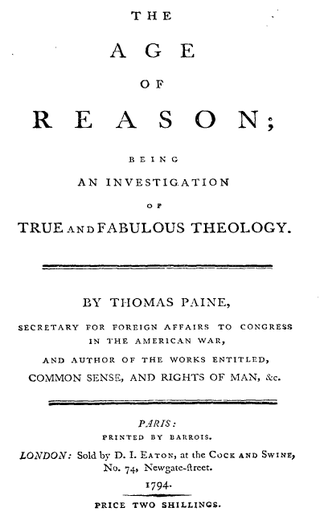

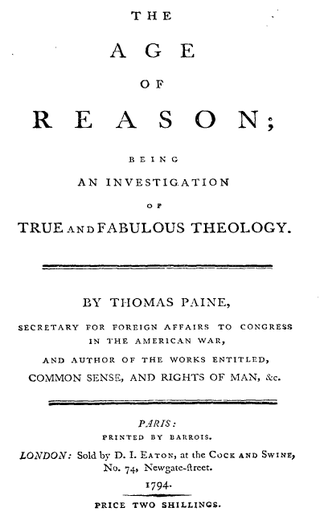

The Age of Reason; Being an Investigation of True and Fabulous Theology is a work by English and American political activist Thomas Paine, arguing for the philosophical position of deism. It follows in the tradition of 18th-century British deism, and challenges institutionalized religion and the legitimacy of the Bible. It was published in three parts in 1794, 1795, and 1807.

The London Corresponding Society (LCS) was a federation of local reading and debating clubs that in the decade following the French Revolution agitated for the democratic reform of the British Parliament. In contrast to other reform associations of the period, it drew largely upon working men and was itself organised on a formal democratic basis.

The Girondins, or Girondists, were a political group during the French Revolution. From 1791 to 1793, the Girondins were active in the Legislative Assembly and the National Convention. Together with the Montagnards, they initially were part of the Jacobin movement. They campaigned for the end of the monarchy, but then resisted the spiraling momentum of the Revolution, which caused a conflict with the more radical Montagnards. They dominated the movement until their fall in the insurrection of 31 May – 2 June 1793, which resulted in the domination of the Montagnards and the purge and eventual mass execution of the Girondins. This event is considered to mark the beginning of the Reign of Terror.

Sir James Mackintosh FRS FRSE was a Scottish jurist, Whig politician and Whig historian. His studies and sympathies embraced many interests. He was trained as a doctor and barrister, and worked also as a journalist, judge, administrator, professor, philosopher and politician.

Rights of Man (1791), a book by Thomas Paine, including 31 articles, posits that popular political revolution is permissible when a government does not safeguard the natural rights of its people. Using these points as a base it defends the French Revolution against Edmund Burke's attack in Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790).

Thomas Erskine, 1st Baron Erskine, was a British Whig lawyer and politician. He served as Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain between 1806 and 1807 in the Ministry of All the Talents.

The Society of the Friends of the People was an organisation in Great Britain that was focused on advocating for parliamentary reform. It was founded by the Whig Party in 1792.

John Thelwall was a radical British orator, writer, political reformer, journalist, poet, elocutionist and speech therapist.

The 1794 Treason Trials, arranged by the administration of William Pitt, were intended to cripple the British radical movement of the 1790s. Over thirty radicals were arrested; three were tried for high treason: Thomas Hardy, John Horne Tooke and John Thelwall. In a repudiation of the government's policies, they were acquitted by three separate juries in November 1794 to public rejoicing. The treason trials were an extension of the sedition trials of 1792 and 1793 against parliamentary reformers in both England and Scotland.

The Revolution Controversy was a British debate over the French Revolution from 1789 to 1795. A pamphlet war began in earnest after the publication of Edmund Burke's Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790), which defended the House of Bourbon, the French aristocracy, and the Catholic Church in France. Because he had supported the American Patriots in their rebellion against Great Britain, Burke's views sent a shockwave through the British Isles. Many writers responded to defend the French Revolution, such as Thomas Paine, Mary Wollstonecraft and William Godwin. Alfred Cobban calls the debate that erupted "perhaps the last real discussion of the fundamentals of politics" in Britain. The themes articulated by those responding to Burke would become a central feature of the radical working-class movement in Britain in the 19th century and of Romanticism. Most Britons celebrated the storming of the Bastille in 1789 and believed that Kingdom of France should be curtailed by a more democratic form of government. However, by December 1795, after the Reign of Terror and the War of the First Coalition, few still supported the French cause.

Sir William Garrow was an English barrister, politician and judge known for his indirect reform of the advocacy system, which helped usher in the adversarial court system used in most common law nations today. He introduced the phrase "presumed innocent until proven guilty", insisting that defendants' accusers and their evidence be thoroughly tested in court. Born to a priest and his wife in Monken Hadley, then in Middlesex, Garrow was educated at his father's school in the village before being apprenticed to Thomas Southouse, an attorney in Cheapside, which preceded a pupillage with Mr. Crompton, a special pleader. A dedicated student of the law, Garrow frequently observed cases at the Old Bailey; as a result Crompton recommended that he become a solicitor or barrister. Garrow joined Lincoln's Inn in November 1778, and was called to the Bar on 27 November 1783. He quickly established himself as a criminal defence counsel, and in February 1793 was made a King's Counsel by HM Government to prosecute cases involving treason and felonies.

John Reeves was a legal historian, civil servant, British magistrate, conservative activist, and the first Chief Justice of Newfoundland. In 1792 he founded the Association for Preserving Liberty and Property against Republicans and Levellers, for the purpose suppressing the "seditious publications" authored by British supporters of the French Revolution—most famously, Thomas Paine's Rights of Man. Because of his counter-revolutionary actions he was regarded by many of his contemporaries as "the saviour of the British state"; in the years after his death, he was warmly remembered as the saviour of ultra-Toryism.

Sir Archibald Macdonald, 1st Baronet was a Scottish-born English lawyer, judge and politician.

John Bowles was an English barrister and pamphleteer. He is known as an opponent of Jacobinism and a prominent conservative writer after the French Revolution.

R v Baillie, also known as the Greenwich Hospital Case, was a 1778 prosecution of Thomas Baillie for criminal libel. The case initiated the legal career of Thomas Erskine. Baillie, the Lieutenant-Governor of the Greenwich Hospital for Seamen, a facility for injured or pensioned off seamen, had noted irregularities and corruption in the hospital, which was formally run by the Earl of Sandwich. After his official reporting of the problems failed to bring about reform in the hospital, Baillie published a pamphlet that was critical of the hospital's officers, alleging that Sandwich had given appointments to pay off political debts; Sandwich ignored the pamphlet but ensured that Baillie was indicted for criminal libel. Baillie hired five barristers, including Erskine, then newly called to the Bar, and appeared before Lord Mansfield in the Court of King's Bench on 23 November 1778.

The Trial of Lord George Gordon for high treason occurred on 5 February 1781 before Lord Mansfield in the Court of King's Bench, as a result of Gordon's role in the riots named after him. Gordon, President of the Protestant Association, had led a protest against the Papists Act 1778, a Catholic Emancipation bill. Intending only to hand in a petition to Parliament, Gordon riled the crowd by postponing of the petition, denouncing Members of Parliament and launching "anti-Catholic harangues". The crowd of protesters fragmented and began looting nearby buildings; by the time the riots had finished a week later, 300 had died. Gordon was almost immediately arrested, and indicted for levying war against the King.

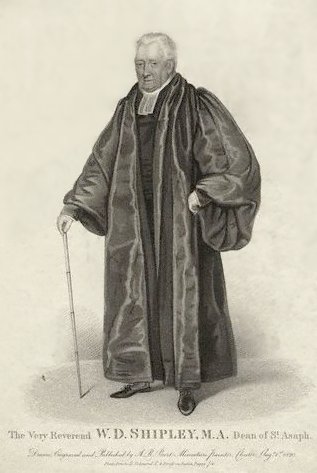

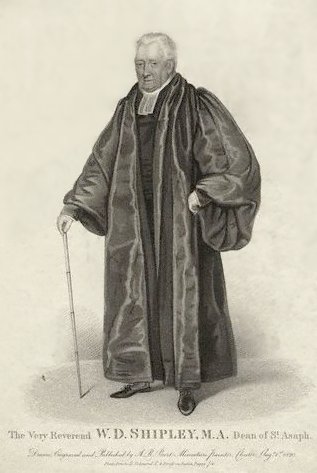

The Case of the Dean of St Asaph, formally R v Shipley, was the 1784 trial of William Davies Shipley, the Dean of St Asaph, for seditious libel. In the aftermath of the American War of Independence, electoral reform had become a substantial issue, and William Pitt the Younger attempted to bring a Bill before Parliament to reform the electoral system. In its support Shipley republished a pamphlet written by his brother-in-law, Sir William Jones, which noted the defects of the existing system and argued in support of Pitt's reforms. Thomas FitzMaurice, the brother of British Prime Minister Earl of Shelburne, reacted by indicting Shipley for seditious libel, a criminal offence which acted as "the government's chief weapon against criticism", since merely publishing something that an individual judge interpreted as libel was enough for a conviction; a jury was prohibited from deciding whether the material was actually libellous. The law was widely seen as unfair, and a Society for Constitutional Information was formed to pay Shipley's legal fees. With financial backing from the society Shipley was able to secure the services of Thomas Erskine KC as his barrister.

The Libel trial of Joseph Howe was a court case heard 2 March 1835 in which newspaper editor Joseph Howe was charged with seditious libel by civic politicians in Nova Scotia. Howe's victory in court was considered monumental at the time. In the first issue of the Novascotian following the acquittal, Howe claimed that "the press of Nova-Scotia is Free." Scholars, such as John Ralston Saul, have argued that Howe's libel victory established the fundamental basis for the freedom of the press in Canada. Historian Barry Cahill writes that the trial was significant in colonial legal history because it was a long delayed replay of the Zenger case (1734).

The Royal Proclamation Against Seditious Writings and Publications was issued by George III of Great Britain on 21 May 1792 in response to the growth of radicalism in Britain inspired by the French Revolution, in particular the phenomenal popularity of Thomas Paine's Rights of Man.