Related Research Articles

In United States law, an Alford plea, also called a Kennedy plea in West Virginia, an Alford guilty plea, and the Alford doctrine, is a guilty plea in criminal court, whereby a defendant in a criminal case does not admit to the criminal act and asserts innocence, but accepts imposition of a sentence. This plea is allowed even if the evidence to be presented by the prosecution would be likely to persuade a judge or jury to find the defendant guilty beyond a reasonable doubt. This can be caused by circumstantial evidence and testimony favoring the prosecution, and difficulty finding evidence and witnesses that would aid the defense.

The insanity defense, also known as the mental disorder defense, is an affirmative defense by excuse in a criminal case, arguing that the defendant is not responsible for their actions due to a psychiatric disease at the time of the criminal act. This is contrasted with an excuse of provocation, in which the defendant is responsible, but the responsibility is lessened due to a temporary mental state. It is also contrasted with the justification of self defense or with the mitigation of imperfect self-defense. The insanity defense is also contrasted with a finding that a defendant cannot stand trial in a criminal case because a mental disease prevents them from effectively assisting counsel, from a civil finding in trusts and estates where a will is nullified because it was made when a mental disorder prevented a testator from recognizing the natural objects of their bounty, and from involuntary civil commitment to a mental institution, when anyone is found to be gravely disabled or to be a danger to themself or to others.

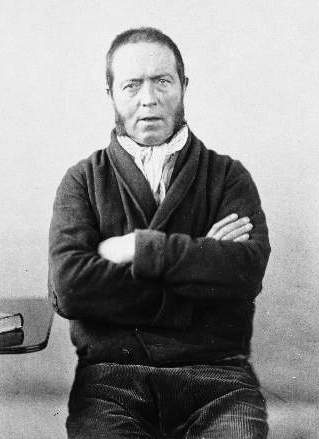

The M'Naghten rule(s) (pronounced, and sometimes spelled, McNaughton) is a legal test defining the defence of insanity, first formulated by House of Lords in 1843. It is the established standard in UK criminal law, and versions have also been adopted in some US states (currently or formerly), and other jurisdictions, either as case law or by statute. Its original wording is a proposed jury instruction:

that every man is to be presumed to be sane, and ... that to establish a defence on the ground of insanity, it must be clearly proved that, at the time of the committing of the act, the party accused was labouring under such a defect of reason, from disease of the mind, as not to know the nature and quality of the act he was doing; or if he did know it, that he did not know he was doing what was wrong.

Nolo contendere is a type of legal plea used in some jurisdictions in the United States. It is also referred to as a plea of no contest or no defense. It is a plea where the defendant neither admits nor disputes a charge, serving as an alternative to a pleading of guilty or not guilty. A no-contest plea, while not technically a guilty plea, typically has the same immediate effect as a guilty plea and is often offered as a part of a plea bargain. The plea is recognized in United States federal criminal courts, and many state criminal courts. In many jurisdictions, a plea of nolo contendere is not a typical right and carries various restrictions on its use.

A plea bargain is an agreement in criminal law proceedings, whereby the prosecutor provides a concession to the defendant in exchange for a plea of guilt or nolo contendere. This may mean that the defendant will plead guilty to a less serious charge, or to one of the several charges, in return for the dismissal of other charges; or it may mean that the defendant will plead guilty to the original criminal charge in return for a more lenient sentence.

The presumption of innocence is a legal principle that every person accused of any crime is considered innocent until proven guilty. Under the presumption of innocence, the legal burden of proof is thus on the prosecution, which must present compelling evidence to the trier of fact. If the prosecution does not prove the charges true, then the person is acquitted of the charges. The prosecution must in most cases prove that the accused is guilty beyond a reasonable doubt. If reasonable doubt remains, the accused must be acquitted. The opposite system is a presumption of guilt.

Discovery, in the law of common law jurisdictions, is a phase of pretrial procedure in a lawsuit in which each party, through the law of civil procedure, can obtain evidence from other parties by means of methods of discovery such as interrogatories, requests for production of documents, requests for admissions and depositions. Discovery can be obtained from nonparties using subpoenas. When a discovery request is objected to, the requesting party may seek the assistance of the court by filing a motion to compel discovery. Conversely, a party or nonparty resisting discovery can seek the assistance of the court by filing a motion for a protective order.

In American procedural law, a continuance is the postponement of a hearing, trial, or other scheduled court proceeding at the request of either or both parties in the dispute, or by the judge sua sponte. In response to delays in bringing cases to trial, some states have adopted "fast-track" rules that sharply limit the ability of judges to grant continuances. However, a motion for continuance may be granted when necessitated by unforeseeable events, or for other reasonable cause articulated by the movant, especially when the court deems it necessary and prudent in the "interest of justice."

In criminal law and in the law of tort, recklessness may be defined as the state of mind where a person deliberately and unjustifiably pursues a course of action while consciously disregarding any risks flowing from such action. Recklessness is less culpable than malice, but is more blameworthy than carelessness.

The Criminal Justice Act 2003 is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It is a wide-ranging measure introduced to modernise many areas of the criminal justice system in England and Wales and, to a lesser extent, in Scotland and Northern Ireland. Large portions of the act were repealed and replaced by the Sentencing Act 2020.

In the law of criminal evidence, a confession is a statement by a suspect in crime which is adverse to that person. Some secondary authorities, such as Black's Law Dictionary, define a confession in more narrow terms, e.g. as "a statement admitting or acknowledging all facts necessary for conviction of a crime," which would be distinct from a mere admission of certain facts that, if true, would still not, by themselves, satisfy all the elements of the offense. The equivalent in civil cases is a statement against interest.

Actual innocence is a special standard of review in legal cases to prove that a charged defendant did not commit the crimes that they were accused of, which is often applied by appellate courts to prevent a miscarriage of justice.

Duress in English law is a complete common law defence, operating in favour of those who commit crimes because they are forced or compelled to do so by the circumstances, or the threats of another. The doctrine arises not only in criminal law but also in civil law, where it is relevant to contract law and trusts law.

In the English law of homicide, manslaughter is a less serious offence than murder, the differential being between levels of fault based on the mens rea or by reason of a partial defence. In England and Wales, a common practice is to prefer a charge of murder, with the judge or defence able to introduce manslaughter as an option. The jury then decides whether the defendant is guilty or not guilty of either murder or manslaughter. On conviction for manslaughter, sentencing is at the judge's discretion, whereas a sentence of life imprisonment is mandatory on conviction for murder. Manslaughter may be either voluntary or involuntary, depending on whether the accused has the required mens rea for murder.

In the law of England and Wales, fitness to plead is the capacity of a defendant in criminal proceedings to comprehend the course of those proceedings. The concept of fitness to plead also applies in Scots and Irish law. Its United States equivalent is competence to stand trial.

English criminal law concerns offences, their prevention and the consequences, in England and Wales. Criminal conduct is considered to be a wrong against the whole of a community, rather than just the private individuals affected. The state, in addition to certain international organisations, has responsibility for crime prevention, for bringing the culprits to justice, and for dealing with convicted offenders. The police, the criminal courts and prisons are all publicly funded services, though the main focus of criminal law concerns the role of the courts, how they apply criminal statutes and common law, and why some forms of behaviour are considered criminal. The fundamentals of a crime are a guilty act and a guilty mental state. The traditional view is that moral culpability requires that a defendant should have recognised or intended that they were acting wrongly, although in modern regulation a large number of offences relating to road traffic, environmental damage, financial services and corporations, create strict liability that can be proven simply by the guilty act.

The right to silence in England and Wales is the protection given to a person during criminal proceedings from adverse consequences of remaining silent. It is sometimes referred to as the privilege against self-incrimination. It is used on any occasion when it is considered the person being spoken to is under suspicion of having committed one or more criminal offences and consequently thus potentially being subject to criminal proceedings.

In the field of criminal law, there are a variety of conditions that will tend to negate elements of a crime, known as defenses. The label may be apt in jurisdictions where the accused may be assigned some burden before a tribunal. However, in many jurisdictions, the entire burden to prove a crime is on the prosecution, which also must prove the absence of these defenses, where implicated. In other words, in many jurisdictions the absence of these so-called defenses is treated as an element of the crime. So-called defenses may provide partial or total refuge from punishment.

Evidential burden or "production burden" is the obligation to produce evidence to properly raise an issue at trial. Failure to satisfy the evidential burden means that an issue cannot be raised at a court of law.

The Code of Criminal Procedure, sometimes called the Code of Criminal Procedure of 1965 or the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1965, is an Act of the Texas State Legislature. The Act is a code of the law of criminal procedure of Texas.

References

- 1 2 3 Exworthy, Tim (2006). "Commentary: UK Perspective on Competency to Stand Trial". J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 34 (4): 466–471. PMID 17185475.

- 1 2 "[2015] 1 Cr App R 27, [2015] Crim LR 359, [2015] EWCA Crim 2, [2015] WLR 2797, [2015] WLR(D) 25, [2015] 1 WLR 2797". Bailii.org. Retrieved 5 January 2016.