A prayer wheel, or mani wheel, is a cylindrical wheel for Buddhist recitation. The wheel is installed on a spindle made from metal, wood, stone, leather, or coarse cotton. Prayer wheels are common in Tibet and areas where Tibetan culture is predominant.

Tibetan Buddhism is a form of Buddhism practiced in Tibet, Bhutan and Mongolia. It also has a sizable number of adherents in the areas surrounding the Himalayas, including the Indian regions of Ladakh, Sikkim, and Arunachal Pradesh, as well as in Nepal. Smaller groups of practitioners can be found in Central Asia, Xinjiang, Inner Mongolia, and some regions of Russia, such as Tuva, Buryatia, and Kalmykia.

Vajrayāna, also known as Mantrayāna, Mantranāya, Guhyamantrayāna, Tantrayāna, Tantric Buddhism, and Esoteric Buddhism, is a Buddhist tradition of tantric practice that developed in the Indian subcontinent and spread to Tibet, Nepal, other Himalayan states, East Asia, and Mongolia.

A mandala is a geometric configuration of symbols. In various spiritual traditions, mandalas may be employed for focusing attention of practitioners and adepts, as a spiritual guidance tool, for establishing a sacred space and as an aid to meditation and trance induction. In the Eastern religions of Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism and Shinto it is used as a map representing deities, or especially in the case of Shinto, paradises, kami or actual shrines. A mandala generally represents the spiritual journey, starting from outside to the inner core, through layers.

Padmasambhava, also known as Guru Rinpoche and the Lotus from Oḍḍiyāna, was a tantric Buddhist Vajra master from medieval India who taught Vajrayana in Tibet. According to some early Tibetan sources like the Testament of Ba, he came to Tibet in the 8th century and helped construct Samye Monastery, the first Buddhist monastery in Tibet. However, little is known about the actual historical figure other than his ties to Vajrayana and Indian Buddhism.

In Buddhism, a stupa is a mound-like or hemispherical structure containing relics that is used as a place of meditation.

The vast majority of surviving Tibetan art created before the mid-20th century is religious, with the main forms being thangka, paintings on cloth, mostly in a technique described as gouache or distemper, Tibetan Buddhist wall paintings, and small statues in bronze, or large ones in clay, stucco or wood. They were commissioned by religious establishments or by pious individuals for use within the practice of Tibetan Buddhism and were manufactured in large workshops by monks and lay artists, who are mostly unknown. Various types of religious objects, such as the phurba or ritual dagger, are finely made and lavishly decorated. Secular objects, in particular jewellery and textiles, were also made, with Chinese influences strong in the latter.

Buddhist culture is exemplified through Buddhist art, Buddhist architecture, Buddhist music and Buddhist cuisine. As Buddhism expanded from the Indian subcontinent it adopted artistic and cultural elements of host countries in other parts of Asia.

The Jokhang, also known as the Qoikang Monastery, Jokang, Jokhang Temple, Jokhang Monastery and Zuglagkang, is a Buddhist temple in Barkhor Square in Lhasa, the capital city of Tibet Autonomous Region of China. Tibetans, in general, consider this temple as the most sacred and important temple in Tibet. The temple is currently maintained by the Gelug school, but they accept worshipers from all sects of Buddhism. The temple's architectural style is a mixture of Indian vihara design, Tibetan and Nepalese design.

Samye, full name Samye Mighur Lhundrub Tsula Khang and Shrine of Unchanging Spontaneous Presence is the first Tibetan Buddhist and Nyingma monastery built in Tibet, during the reign of King Trisong Deutsen. Shantarakshita began construction around 763, and Tibetan Vajrayana founder Guru Padmasambhava tamed the local spirits for its completion in 779. The first Tibetan monks were ordained there. Samye was destroyed during the Cultural Revolution then rebuilt after 1988.

The phurba or kīla is a three-sided peg, stake, knife, or nail-like ritual implement deeply rooted in Indo-Tibetan Buddhism and Bön traditions. Its primary association is with the meditational deity Vajrakīlaya, embodying the essence of transformative power. The etymology and historical context of the term reveal some debate. Both the Sanskrit word "kīla" and the Tibetan "phurba" are used interchangeably in sources.

A thangka is a Tibetan Buddhist painting on cotton, silk appliqué, usually depicting a Buddhist deity, scene, or mandala. Thangkas are traditionally kept unframed and rolled up when not on display, mounted on a textile backing somewhat in the style of Chinese scroll paintings, with a further silk cover on the front. So treated, thangkas can last a long time, but because of their delicate nature, they have to be kept in dry places where moisture will not affect the quality of the silk. Most thangkas are relatively small, comparable in size to a Western half-length portrait, but some are extremely large, several metres in each dimension; these were designed to be displayed, typically for very brief periods on a monastery wall, as part of religious festivals. Most thangkas were intended for personal meditation or instruction of monastic students. They often have elaborate compositions including many very small figures. A central deity is often surrounded by other identified figures in a symmetrical composition. Narrative scenes are less common, but do appear.

Vikramashila was one of the three most important Buddhist monasteries in India during the Pala Empire, along with Nalanda and Odantapuri. Its location is now the site of Antichak village near Kahalgaon, Bhagalpur district in Bihar.

A ganacakra is also known as tsok, ganapuja, cakrapuja or ganacakrapuja. It is a generic term for various tantric assemblies or feasts, in which practitioners meet to chant mantra, enact mudra, make votive offerings and practice various tantric rituals as part of a sādhanā, or spiritual practice. The ganachakra often comprises a sacramental meal and festivities such as dancing, spirit possession, and trance; the feast generally consisting of materials that were considered forbidden or taboo in medieval India like meat, fish, and wine. As a tantric practice, forms of gaṇacakra are practiced today in Hinduism, Bön and Vajrayāna Buddhism.

Diamond Way Buddhism is a lay organization within the Karma Kagyu school of Tibetan Buddhism. The first Diamond Way Buddhist center was founded in 1972 by Hannah Nydahl and Ole Nydahl in Copenhagen under the guidance of Rangjung Rigpe Dorje, 16th Karmapa. Today there are approximately 650 centers worldwide, directed by Ole Nydahl under the guidance of Trinley Thaye Dorje, one of two claimants to the title of the 17th Karmapa. Buddhist teachers such as Sherab Gyaltsen Rinpoche, Lama Jigme Rinpoche and Nedo Kuchung Rinpoche visit Diamond Way Buddhism centers and large meditation courses.

Buddhism is the state religion of Bhutan. According to a 2012 report by the Pew Research Center, 74.7% of the country's population practices Buddhism.

Devotion, a central practice in Buddhism, refers to commitment to religious observances or to an object or person, and may be translated with Sanskrit or Pāli terms like saddhā, gārava or pūjā. Central to Buddhist devotion is the practice of Buddhānussati, the recollection of the inspiring qualities of the Buddha. Although buddhānussati was an important aspect of practice since Buddhism's early period, its importance was amplified with the arising of Mahāyāna Buddhism. Specifically, with Pure Land Buddhism, many forms of devotion were developed to recollect and connect with the celestial Buddhas, especially Amitābha.

Chinese Esoteric Buddhism refers to traditions of Tantra and Esoteric Buddhism that have flourished among the Chinese people. The Tantric masters Śubhakarasiṃha, Vajrabodhi and Amoghavajra, established the Esoteric Buddhist Zhenyan tradition from 716 to 720 during the reign of Emperor Xuanzong of Tang. It employed mandalas, mantras, mudras, abhiṣekas, and deity yoga. The Zhenyan tradition was transported to Japan as Shingon Buddhism by Kūkai as well as influencing Korean Buddhism and Vietnamese Buddhism. The Song dynasty (960–1279) saw a second diffusion of Esoteric texts. Esoteric Buddhist practices continued to have an influence into the late imperial period and Tibetan Buddhism was also influential during the Yuan dynasty period and beyond. In the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) through to the modern period, esoteric practices and teachings became absorbed and merged with the other Chinese Buddhist traditions to a large extent.

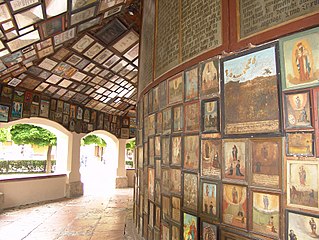

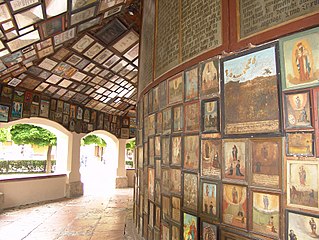

A votive offering or votive deposit is one or more objects displayed or deposited, without the intention of recovery or use, in a sacred place for religious purposes. Such items are a feature of modern and ancient societies and are generally made to gain favor with supernatural forces.