1980s and 1990s

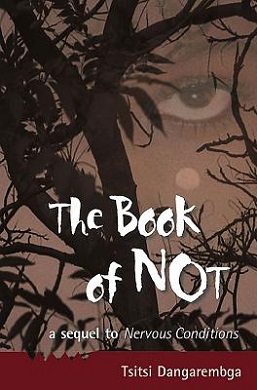

In 1985, Dangarembga's short story "The Letter" won second place in a writing competition arranged by the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency, and was published in Sweden in the anthology Whispering Land. [3] [4] In 1987, her play She No Longer Weeps, which she wrote during her university years, was published in Harare. [4] [12] Her first novel, Nervous Conditions , was published in 1988 in the United Kingdom, and a year later in the United States. [3] [4] [6] [10] She wrote it in 1985, but experienced difficulties getting it published; rejected by four Zimbabwean publishers, she eventually found a willing publisher in the London-based Women's Press. [6] [10] Nervous Conditions, the first novel written in English by a black woman from Zimbabwe, received domestic and international acclaim, and was awarded the Commonwealth Writers' Prize (Africa region) in 1989. [3] [4] [6] [10] [13] Her work is included in the 1992 anthology Daughters of Africa , edited by Margaret Busby. [14] Nervous Conditions is considered one of the best African novels ever written, [15] and was included on the BBC's 2018 list of top 100 books that have shaped the world. [16]

In 1989, Dangarembga went to Germany to study film direction at the German Film and Television Academy Berlin. [3] [4] [6] She produced a number of films while in Berlin, including a documentary aired on German television. [4] In 1992, she founded Nyerai Films, a production company based in Harare. [3] She wrote the story for the film Neria , made in 1991, which became the highest-grossing film in Zimbabwean history. [17] Her 1996 film Everyone's Child , the first feature film directed by a black Zimbabwean woman, was shown internationally, including at the Dublin International Film Festival. [3] [4] The film, shot on location in Harare and Domboshava, follows the tragic stories of four siblings after their parents die of AIDS. [4]

2000 onwards

In 2000, Dangarembga moved back to Zimbabwe with her family, and continued her work with Nyerai Films. In 2002, she founded the International Images Film Festival. [18] Her 2005 film Kare Kare Zvako won the Short Film Award and Golden Dhow at the Zanzibar International Film Festival, and the African Short Film Award at the Milan Film Festival. [3] Her 2006 film Peretera Maneta received the UNESCO Children's and Human Rights Award and won the Zanzibar International Film Festival. [3] She is the executive director of the organization Women Filmmakers of Zimbabwe and the founding director of the International Images Film Festival for Women of Harare (IIFF). [19] As of 2010, she has also served on the board of the Zimbabwe College of Music for five years, including two years as chair. [3] [8] She is a founding member of the Institute for Creative Arts for Progress for Creative Arts in Africa (ICAPA). [20]

Asked about her lack of writing since Nervous Conditions, Dangarembga explained in 2004: "firstly, the novel was published only after I had turned to film as a medium; secondly, Virginia Woolf's shrewd observation that a woman needs £500 and a room of her own in order to write is entirely valid. Incidentally, I am moving and hope that, for the first time since Nervous Conditions, I shall have a room of my own. I'll try to ignore the bit about £500." [21] Indeed, two years later in 2006, she published her second novel, The Book of Not , a sequel to Nervous Conditions. [4] She also became involved in politics, and in 2010 was named education secretary of the Movement for Democratic Change political party led by Arthur Mutambara. [3] [8] She cited her background coming from a family of educators, her brief stint as a teacher, and her "practical, if not formal," involvement in the education sector as preparing her for the role. [8] She completed doctoral studies in African studies at Humboldt University of Berlin, and wrote her PhD thesis on the reception of African film. [3] [8]

She was a judge for the 2014 Etisalat Prize for Literature. [22] In 2016, she was selected by the Rockefeller Foundation Bellagio Center for their Artists in Residency program. [23] Her third novel, This Mournable Body, a sequel to The Book of Not and Nervous Conditions, was published in 2018 by Graywolf Press in the US, and in the UK by Faber and Faber in 2020, described by Alexandra Fuller in The New York Times as "another masterpiece" [13] and by Novuyo Rosa Tshuma in The Guardian as "magnificent ... another classic" [24] This Mournable Body was one of the six novels shortlisted for the 2020 Booker Prize, chosen from 162 submissions. [25] [26]

In an interview with Bhakti Shringarpure for Bomb magazine, Dangaremgba discussed the rationale behind her novels: "My first publisher, the late Ros de Lanerolle, asked me to write a sequel to Nervous Conditions. Writing the sequel, I realized the second book would deal only with the middle part of the protagonist's life. ... [and] offered no answers to the questions raised in Nervous Conditions concerning how life with any degree of agency is possible for such people. ... I was captivated by the idea of writing a trilogy about a very ordinary person who starts off as an impoverished rural girl in colonial Rhodesia and has to try to build a meaningful life for herself. The form has also allowed me to engage with some aspects of Zimbabwe's national development from a personal rather than a political angle." [27]

In 2019, Dangarembga was announced as a finalist for the St. Francis College Literary Prize, a biennial award recognizing outstanding fiction by writers in the middle stages of their careers, which was eventually won that year by Samantha Hunt. [28] [29]

On 31 July 2020 Dangarembga was arrested in Harare, Zimbabwe, ahead of anti-corruption protests. [30] Later that year she was on the list of the BBC's 100 Women announced on 23 November 2020. [31]

In September 2020, Dangarembga was announced as the University of East Anglia's inaugural International Chair of Creative Writing, from 2021 to 2022. [32] [33]

Dangarembga won the 2021 PEN International Award for Freedom of Expression, given annually since 2005 to honour writers who continue working despite being persecuted for their writing. [34] [35] [36] [37]

In June 2021, it was announced that Dangarembga would be the recipient of the prestigious 2021 Peace Prize awarded by the German book publishers and booksellers association, [38] making her the first black woman to be honoured with the award since it was inaugurated in 1950. [39]

In July 2021, she was elected to honorary Fellowship of Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge. [11]

Dangarembga was chosen by English PEN as winner of the 2021 PEN Pinter Prize, awarded annually to a writer who, in the words spoken by Harold Pinter on receiving his Nobel Prize for Literature, casts an "unflinching, unswerving" gaze upon the world and shows a "fierce intellectual determination... to define the real truth of our lives and our societies". [40] In her acceptance speech at the British Library on 11 October 2021, Dangarembga named the Ugandan novelist Kakwenza Rukirabashaija as the International Writer of Courage Award. [41] [42] [43]

In 2022, Dangarembga was selected to receive a Windham-Campbell Literature Prize for fiction. [44]

In June 2022, an arrest warrant was issued against Tsitsi Dangarembga. [45] She was prosecuted for incitement to public violence and violation of anti-Covid rules after an anti-government demonstration organized at the end of July 2020. [46] [47]

On 28 September 2022, Dangarembga was officially convicted of promoting public violence after her and her friend, Julie Barnes, walked around Harare in a peaceful protest while holding placards that read “We Want Better. Reform Our Institutions”. Dangarembga was given a $110 fine and a suspended six-month jail sentence. She announced that she planned to appeal her verdict amid human rights groups claiming that her prosecution was a direct result of President Emmerson Mnangagwa’s attempts to “silence opposition in the long-troubled southern African country”. [48] [49] [50] On 8 May 2023, it was announced that Dangarembga's conviction had been overturned after she appealed the initial conviction in 2022. [51] [52] [53]