Klezmer is an instrumental musical tradition of the Ashkenazi Jews of Central and Eastern Europe. The essential elements of the tradition include dance tunes, ritual melodies, and virtuosic improvisations played for listening; these would have been played at weddings and other social functions. The musical genre incorporated elements of many other musical genres including Ottoman music, Baroque music, German and Slavic folk dances, and religious Jewish music. As the music arrived in the United States, it lost some of its traditional ritual elements and adopted elements of American big band and popular music. Among the European-born klezmers who popularized the genre in the United States in the 1910s and 1920s were Dave Tarras and Naftule Brandwein; they were followed by American-born musicians such as Max Epstein, Sid Beckerman and Ray Musiker.

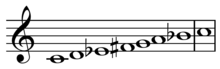

Dorian mode or Doric mode can refer to three very different but interrelated subjects: one of the Ancient Greek harmoniai ; one of the medieval musical modes; or—most commonly—one of the modern modal diatonic scales, corresponding to the piano keyboard's white notes from D to D, or any transposition of itself.

In music, the Phrygian dominant scale is the fifth mode of the harmonic minor scale, the fifth being the dominant. Also called the altered Phrygian scale, dominant flat 2 flat 6, or Freygish scale. It resembles the Phrygian mode but with a major third, rather than a minor third.

A Duma is a sung epic poem which originated in Ukraine during the Hetmanate Era in the Sixteenth century. Historically, dumy were performed by itinerant Cossack bards called kobzari, who accompanied themselves on a kobza or a torban, but after the abolition of Hetmanate by the Empress Catherine II of Russia the epic singing became the domain of blind itinerant musicians who retained the kobzar appellation and accompanied their singing by playing a bandura or a relya/lira. Dumas are sung in recitative, in the so-called "duma mode", a variety of the Dorian mode with a raised fourth degree.

Dave Tarras was a Ukrainian-born American klezmer clarinetist and bandleader, a celebrated klezmer musician, instrumental in Klezmer revival.

Jewish music is the music and melodies of the Jewish people. There exist both traditions of religious music, as sung at the synagogue and domestic prayers, and of secular music, such as klezmer. While some elements of Jewish music may originate in biblical times, differences of rhythm and sound can be found among later Jewish communities that have been musically influenced by location. In the nineteenth century, religious reform led to composition of ecclesiastic music in the styles of classical music. At the same period, academics began to treat the topic in the light of ethnomusicology. Edwin Seroussi has written, "What is known as 'Jewish music' today is thus the result of complex historical processes". A number of modern Jewish composers have been aware of and influenced by the different traditions of Jewish music.

Parting traditions or parting customs are various traditions, customs, and habits used by people to acknowledge the parting of individuals or groups of people from each other.

Michael Alpert is a klezmer musician and Yiddish singer, songwriter, multi-instrumentalist, scholar and educator who has been called a key figure in the klezmer revitalization, beginning in the 1970s. He has performed solo and in a number of ensembles since that time, including Brave Old World, Kapelye, Khevrisa, The Brothers Nazaroff, Voices of Ashkenaz and The An-Sky Ensemble, and has collaborated with clarinetist David Krakauer, hip-hop artist Socalled, singer/songwriter/actor Daniel Kahn, bandurist Julian Kytasty, violinist Itzhak Perlman, ethnomusicologist and musician Walter Zev Feldman, trumpeter/composerFrank London and numerous others.

Mark Slobin is an American scholar and ethnomusicologist who has written extensively on the subject of East European Jewish music and klezmer music, as well as the music of Afghanistan, where he conducted research beginning in 1967. He is Winslow-Kaplan Professor of Music Emeritus at Wesleyan University, where he taught both music and American Studies from 1971 to 2016.

Moisei Iakovlevich Beregovsky was a Soviet Jewish folklorist and ethnomusicologist from Ukraine, who published mainly in Russian and Yiddish. He has been called the "foremost ethnomusicologist of Eastern European Jewry". His research and life's work included the collection, transcription and analysis of the melodies, texts and culture of Yiddish folk song, wordless melodies (nigunim), East European Jewish instrumental music for both dancing and listening, Purim plays, and exploration of the relationship between East European Jewish and Ukrainian traditional music.

Susman Kiselgof was a Russian-Jewish folksong collector and pedagogue associated with the Society for Jewish Folk Music in St. Petersburg. Like his contemporary Joel Engel, he conducted fieldwork in the Russian Empire to collect Jewish religious and secular music. Materials he collected were used in the compositions of such figures as Joseph Achron, Lev Pulver, and Alexander Krein.

Max Leibowitz was an American klezmer violinist, composer and bandleader in New York City primarily in the 1910s and 1920s.

Israel J. Hochman was a Russian-born Jewish American violinist, klezmer bandleader, music arranger, and recording artist in early Twentieth Century New York City. He recorded prolifically for Edison Records, Emerson Records, Okeh Records, and Brunswick Records during the period of 1916 to 1924. He was one of a handful of bandleaders such as Abe Schwartz, Joseph Frankel and Max Leibowitz whose recordings are considered to make up the golden age of American klezmer.

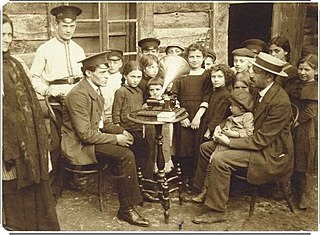

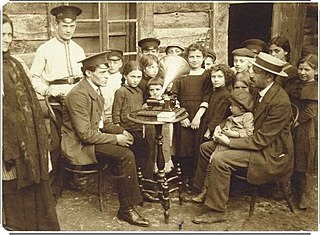

Sofia Magid was a Soviet Jewish ethnographer and folklorist whose career lasted from the 1920s to the 1950s. Among the materials she collected were folksongs of Volhynian and Belarusian Jews and among the only prewar field recordings of European klezmer string ensembles, as well as the music of Russians and other ethnic groups of the USSR. Although she was largely unknown abroad during her lifetime, in recent years she has been seen alongside Moshe Beregovski and other Soviet Jewish ethnographers as an important scholar and collector of Jewish music.

H. Steiner was a klezmer violinist who recorded for two discs of violin and cimbalom duets for the Gramophone Company in around 1909. Although he had a small musical output and his biography is mostly unknown, his recordings serve an important function for Klezmer revival musicians as they are rare examples of recorded European klezmer violin style.

Pedotser, also pronounced Pedutser in some Yiddish dialects, was the popular name of Aron-Moyshe Kholodenko, a nineteenth century Klezmer violin virtuoso, composer and bandeader from Berdychiv, Russian Empire. He was one of a number of virtuosic klezmers of the nineteenth century, alongside Yosef Drucker "Stempenyu", Yehiel Goyzman "Alter Chudnover" and Josef Gusikov.

Avraham-Yehoshua Makonovetsky was a Russian-Jewish Klezmer violinist who acted as a key informant to the Soviet Ethnomusicologist Moisei Beregovsky in the 1930s. His extensive handwritten manuscripts, which are now in the collection of the Vernadsky National Library of Ukraine, serve as a rare example of nineteenth-century Klezmer violin music.

Alter Chudnover, whose real name was Yehiel Goyzman or Hausman, was a nineteenth century Klezmer violinist from the Russian Empire. He was one of a number of virtuosic klezmers of the nineteenth century, alongside Yosef Drucker "Stempenyu", A. M. Kholodenko "Pedotser" and Josef Gusikov. He was also an early teacher to the violinist Mischa Elman.

Stempenyu was the popular name of Iosif Druker, a klezmer violin virtuoso, bandleader and composer from Berdychiv, Russian Empire. He was one of a handful of celebrity nineteenth century Jewish folk violinists from Ukraine; others included Aron-Moyshe Kholodenko "Pedotser" and Yechiel Goyzman "Alter Chudnover" from Chudniv. Sholem Aleichem loosely based his 1888 novel Stempenyu: A Jewish Novel on the real-life Stempenyu; it was adapted into various stage and film versions in the twentieth century.

Belf's Romanian Orchestra was a Jewish music recording ensemble from the Russian Empire. Although little is known about them, their numerous recordings for Syrena Rekord during the period of 1911 to 1914 are among the earliest documented examples of recorded klezmer music and are played in a style very different from the better-known American klezmer recordings of the 1910s and 1920s.