Related Research Articles

Northern Ireland is one of the four countries of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland. It was created as a separate legal entity on 3 May 1921 under the Government of Ireland Act 1920. The new autonomous Northern Ireland was formed from six of the nine counties of Ulster: four counties with unionist majorities – Antrim, Armagh, Down, and Londonderry – and two counties with slight Irish nationalist majorities – Fermanagh and Tyrone – in the 1918 General Election. The remaining three Ulster counties with larger nationalist majorities were not included. In large part unionists, at least in the north-east, supported its creation while nationalists were opposed.

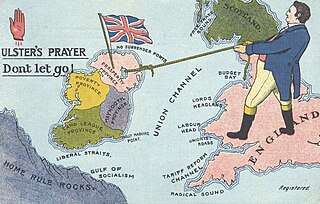

Unionism in Ireland is a political tradition that professes loyalty to the crown of the United Kingdom and to the union it represents with England, Scotland and Wales. The overwhelming sentiment of Ireland's Protestant minority, unionism mobilised in the decades following Catholic Emancipation in 1829 to oppose restoration of a separate Irish parliament. Since Partition in 1921, as Ulster unionism its goal has been to retain Northern Ireland as a devolved region within the United Kingdom and to resist the prospect of an all-Ireland republic. Within the framework of the 1998 Belfast Agreement, which concluded three decades of political violence, unionists have shared office with Irish nationalists in a reformed Northern Ireland Assembly. As of February 2024, they no longer do so as the larger faction: they serve in an executive with an Irish republican First Minister.

The Northern Ireland Labour Party (NILP) was a political party in Northern Ireland which operated from 1924 until 1987.

The Volunteer Political Party (VPP) was a loyalist political party launched in Northern Ireland on 22 June 1974 by members of the then recently legalised Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF). The Chairman was Ken Gibson from East Belfast, an ex-internee and UVF chief of staff at the time. The success of the Ulster Workers Council Strike had shown some UVF leaders the political power they held and they sought to develop this potential further. The UVF had been banned by the Government of Northern Ireland in 1966, but was legalised at the same time as Sinn Féin by Labour Secretary of State Merlyn Rees in April 1974 in order to encourage a political path for Loyalist and republican paramilitary groups.

The Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA) (Irish: Cumann Cearta Sibhialta Thuaisceart Éireann) was an organisation that campaigned for civil rights in Northern Ireland during the late 1960s and early 1970s. Formed in Belfast on 9 April 1967, the civil rights campaign attempted to achieve reform by publicising, documenting, and lobbying for an end to discrimination against Catholics in areas such as elections (which were subject to gerrymandering and property requirements), discrimination in employment, in public housing and abuses of the Special Powers Act.

Ulster loyalism is a strand of Ulster unionism associated with working class Ulster Protestants in Northern Ireland. Like other unionists, loyalists support the continued existence of Northern Ireland within the United Kingdom, and oppose a united Ireland independent of the UK. Unlike other strands of unionism, loyalism has been described as an ethnic nationalism of Ulster Protestants and "a variation of British nationalism". Loyalists are often said to have a conditional loyalty to the British state so long as it defends their interests. They see themselves as loyal primarily to the Protestant British monarchy rather than to British governments and institutions, while Garret FitzGerald argued they are loyal to 'Ulster' over 'the Union'. A small minority of loyalists have called for an independent Ulster Protestant state, believing they cannot rely on British governments to support them. The term 'loyalism' is usually associated with paramilitarism.

The Ulster Workers' Council (UWC) strike was a general strike that took place in Northern Ireland between 15 May and 28 May 1974, during "the Troubles". The strike was called by unionists who were against the Sunningdale Agreement, which had been signed in December 1973. Specifically, the strikers opposed the sharing of political power with Irish nationalists, and the proposed role for the Republic of Ireland's government in running Northern Ireland.

George Seawright was a Scottish-born unionist politician in Northern Ireland and loyalist paramilitary in the Ulster Volunteer Force. He was assassinated by the Irish People's Liberation Organisation in 1987.

The Loyalist Association of Workers (LAW) was a militant unionist organisation in Northern Ireland that sought to mobilise trade union members in support of the loyalist cause. It became notorious for a one-day strike in 1973 that ended in widespread violence.

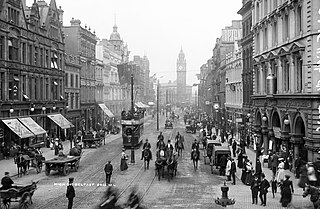

Belfast is the capital of Northern Ireland, and throughout its modern history has been a major commercial and industrial centre. In the late 20th century manufacturing industries that had existed for several centuries declined, particularly shipbuilding. The city's history has occasionally seen conflict between different political factions who favour different political arrangements between Ireland and Great Britain. Since the Good Friday Agreement, the city has been relatively peaceful and major redevelopment has occurred, especially in the inner city and dock areas.

The British and Irish Communist Organisation (B&ICO) was a small group based in London, Belfast, Cork, and Dublin. Its leader was Brendan Clifford. The group produced a number of pamphlets and regular publications, including The Irish Communist and Workers Weekly in Belfast. Τhe group currently expresses itself through Athol Books with its premier publication being the Irish Political Review. The group also continues to publish Church & State, Irish Foreign Affairs, Labour Affairs and Problems.

Henry Cassidy Midgley, PC (NI), known as Harry Midgley was a prominent trade-unionist and politician in Northern Ireland. Born to a working-class Protestant family in Tiger's Bay, north Belfast, he followed his father into the shipyard. After serving on the Western Front in the Great War, he became an official in a textile workers union and a leading light in the Belfast Labour Party (BLP). He represented the party's efforts in the early 1920s to provide a left opposition to the Unionist government of the new Northern Ireland while remaining non-committal on the divisive question of Irish partition.

Sir Richard Dawson Bates, 1st Baronet, known as Dawson Bates, was an Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) member of the House of Commons of Northern Ireland.

William Hull was a loyalist activist in Northern Ireland. Hull was a leading figure in political, paramilitary and trade union circles during the early years of the Troubles. He is most remembered for being the leader of the Loyalist Association of Workers, a loyalist trade union-styled movement that briefly enjoyed a mass membership before fading.

Thomas Henry Sloan (1870–1941) was an Irish unionist and co-founder of the Independent Orange Order (IOO). The choice of a loyalist workers association over the official Conservative Unionist nominee, he represented the Belfast South constituency as an Independent Unionist at the Westminster parliament from 1902 to 1910. He and members of the IOO supported workers in the Belfast Lockout of 1907.

Thompson Donald was a Northern Irish Unionist politician.

The Belfast Protestant Association was a populist evangelical political movement in the early 20th-century.

Kenneth Gibson was a Northern Irish politician who was the Chairman of the Volunteer Political Party (VPP), which he had helped to form in 1974. He also served as a spokesman and Chief of Staff of the loyalist paramilitary organisation, the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF).

The Belfast Dock strike or Belfast lockout took place in Belfast, Ireland from 26 April to 28 August 1907. The strike was called by Liverpool-born trade union leader James Larkin who had successfully organised the dock workers to join the National Union of Dock Labourers (NUDL). The dockers, both Protestant and Catholic, had gone on strike after their demand for union recognition was refused. They were soon joined by carters, shipyard workers, sailors, firemen, boilermakers, coal heavers, transport workers, and women from the city's largest tobacco factory. Most of the dock labourers were employed by powerful tobacco magnate Thomas Gallaher, chairman of the Belfast Steamship Company and owner of Gallaher's Tobacco Factory.

The Troubles of the 1920s was a period of conflict in what is now Northern Ireland from June 1920 until June 1922, during and after the Irish War of Independence and the partition of Ireland. It was mainly a communal conflict between Protestant unionists, who wanted to remain part of the United Kingdom, and Catholic Irish nationalists, who backed Irish independence. During this period, more than 500 people were killed in Belfast alone, 500 interned and 23,000 people were made homeless in the city, while approximately 50,000 people fled the north of Ireland due to intimidation. Most of the victims were Nationalists (73%) with civilians being far more likely to be killed compared to the military, police or paramilitaries.

References

- 1 2 3 4 Paul Bew, Peter Gibbon and Henry Patterson, Northern Ireland: 1921 / 2001 Political Forces and Social Classes, Serif (London 2002), ISBN 1-897959-38-9, pp. 16–17.

- ↑ J. M. Andrews chaired UULA meetings later becoming a Minister of Labour from 1921 to 1937. He was Minister of Finance from 1937 to 1940, when on the death of Lord Craigavon, he became the second Prime Minister of Northern Ireland.

- ↑ Brian Lalor, The Encyclopaedia of Ireland, Gill & Macmillan (Ireland 2003), ISBN 0-7171-3000-2, pp. 23–24

- ↑ John F. Harbinson, The Ulster Unionist Party, 1882–1973, p. 67.

- 1 2 Jurgen Elvert, Northern Ireland, past and present, Stuttgart: F. Steiner, 1994. ISBN 3-515-06102-9, p. 93.

- ↑ Graham S. Walker, A History of the Ulster Unionist Party: Protest, pragmatism and pessimism , Manchester University Press (2004), ISBN 978-0-7190-6109-7, p. 44.

- 1 2 3 4 Bew, Gibbon and Patterson, Northern Ireland (2002), pp. 18–19.

- 1 2 Elvert, Northern Ireland, past and present (1994), p. 94.

- ↑ Harbinson, The Ulster Unionist Party, 1882–1973, p. 185.

- 1 2 3 Harbinson, The Ulster Unionist Party, 1882–1973, p. 68.

- ↑ Peter Barberis et al., Encyclopedia of British and Irish Political Organizations, p. 255.