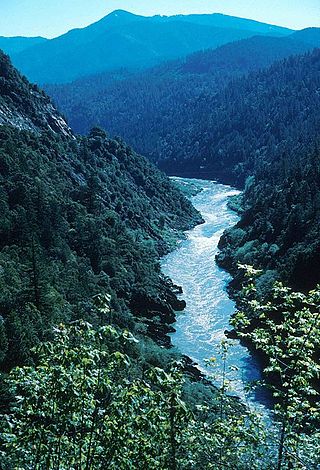

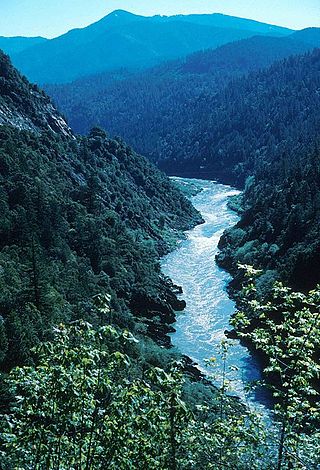

The Klamath River flows 257 miles (414 km) through Oregon and northern California in the United States, emptying into the Pacific Ocean. By average discharge, the Klamath is the second largest river in California after the Sacramento River. Its nearly 16,000-square-mile (41,000 km2) watershed stretches from the high desert of south-central Oregon to the temperate rainforest of the North Coast. Unlike most rivers, the Klamath begins in a desert region and flows through the rugged Cascade Range and Klamath Mountains before reaching the ocean; National Geographic magazine has called the Klamath "a river upside down".

The Chinook salmon is the largest and most valuable species of Pacific salmon. Its common name is derived from the Chinookan peoples. Other vernacular names for the species include king salmon, Quinnat salmon, Tsumen, spring salmon, chrome hog, Blackmouth, and Tyee salmon. The scientific species name is based on the Russian common name chavycha (чавыча).

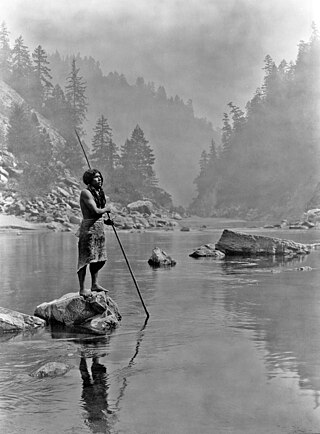

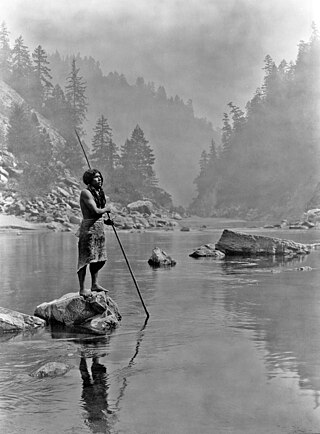

Hupa are a Native American people of the Athabaskan-speaking ethnolinguistic group in northwestern California. Their endonym is Natinixwe, also spelled Natinook-wa, meaning "People of the Place Where the Trails Return". The Karuk name was Kishákeevar / Kishakeevra. The majority of the tribe is enrolled in the federally recognized Hoopa Valley Tribe.

The Link River Dam is a concrete gravity dam on the Link River in the city of Klamath Falls, Oregon, United States. It was built in 1921 by the California Oregon Power Company (COPCO), the predecessor of PacifiCorp, which continues to operate the dam. The dam is owned by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation.

The Klamath Project is a water-management project developed by the United States Bureau of Reclamation to supply farmers with irrigation water and farmland in the Klamath Basin. The project also supplies water to the Tule Lake National Wildlife Refuge, and the Lower Klamath National Wildlife Refuge. The project was one of the first to be developed by the Reclamation Service, which later became the Bureau of Reclamation.

Condit Hydroelectric Project was a development on the White Salmon River in the U.S. state of Washington. It was completed in 1913 to provide electrical power for local industry, and is listed in the National Register of Historic Places as an engineering and architecture landmark.

The Yurok are an Indigenous people from along the Klamath River and Pacific coast, whose homelands are located in present-day California stretching from Trinidad in the south to Crescent City in the north.

The Klamath Basin is the region in the U.S. states of Oregon and California drained by the Klamath River. It contains most of Klamath County and parts of Lake and Jackson counties in Oregon, and parts of Del Norte, Humboldt, Modoc, Siskiyou, and Trinity counties in California. The 15,751-square-mile (40,790 km2) drainage basin is 35% in Oregon and 65% in California. In Oregon, the watershed typically lies east of the Cascade Range, while California contains most of the river's segment that passes through the mountains. In the Oregon-far northern California segment of the river, the watershed is semi-desert at lower elevations and dry alpine in the upper elevations. In the western part of the basin, in California, however, the climate is more of temperate rainforest, and the Trinity River watershed consists of a more typical alpine climate.

Dam removal is the process of demolishing a dam, returning water flow to the river. Arguments for dam removal consider whether their negative effects outweigh their benefits. The benefits of dams include hydropower production, flood control, irrigation, and navigation. Negative effects of dams include environmental degradation, such as reduced primary productivity, loss of biodiversity, and declines in native species; some negative effects worsen as dams age, like structural weakness, reduced safety, sediment accumulation, and high maintenance expense. The rate of dam removals in the United States has increased over time, in part driven by dam age. As of 1996, 5,000 large dams around the world were more than 50 years old. In 2020, 85% percent of dams in the United States are more than 50 years old. In the United States roughly 900 dams were removed between 1990 and 2015, and by 2015, the rate was 50 to 60 per year. France and Canada have also completed significant removal projects. Japan's first removal, of the Arase Dam on the Kuma River, began in 2012 and was completed in 2017. A number of major dam removal projects have been motivated by environmental goals, particularly restoration of river habitat, native fish, and unique geomorphological features. For example, fish restoration motivated the Elwha Ecosystem Restoration and the dam removal on the river Allier, while recovery of both native fish and of travertine deposition motivated the restoration of Fossil Creek.

The John C. Boyle Dam is a hydroelectric dam located in southern Oregon, United States. It is on the upper Klamath River, south (downstream) of Keno, and about 12 miles (19 km) north of the California border. Originally developed and known as Big Bend, the John C. Boyle dam and powerhouse complex was re-dedicated to honor the pioneer hydroelectric engineer who was responsible for the design of virtually all of the Klamath Hydroelectric Project.

The Klamath River is a river in southern Oregon and northern California in the United States. This article describes its course.

The 2002 Klamath River fish kill occurred on the Klamath River in California in September 2002. According to the official estimate of mortality, about 34,000 fish died. Though some counts may estimate over 70,000 adult chinook salmon were killed when returning to the river to spawn, making it the largest salmon kill in the history of the Western United States. Besides the chinook salmon, other fish that perished include: steelhead, coho salmon, sculpins, speckled dace, and Klamath smallscale sucker.

Iron Gate Dam is an earthfill hydroelectric dam on the Klamath River in northern California, outside Hornbrook, California, that opened in 1964. The dam blocks the Klamath River to create the Iron Gate Lake Reservoir. It is the lowermost of a series of power dams on the river, the Klamath River Hydroelectric Project, operated by PacifiCorp. It also poses the first barrier to migrating salmon in the Klamath. The Iron Gate Fish Hatchery was placed just after the dam, hatching salmon and steelhead that are released back into the river.

River of Renewal: Myth and History in the Klamath Basin is a 2006 book by Stephen Most detailing the challenges in balancing economic and ecological concerns in the Klamath Basin region of the United States. The book shows clashes between federal and state government agencies, American Indian tribes, hydroelectric dam operators, and the farming and commercial fishery industries, detailing challenges and controversies around the irrigation of farmland and the preservation of the wild salmon population.

Copco Lake was an artificial lake on the Klamath River in Siskiyou County, California, near the Oregon border. The lake's waters were impounded by the Copco Number 1 Dam, which was completed in 1922 as part of the Klamath River Hydroelectric Project.

John C. Boyle Reservoir is an artificial impoundment behind John C. Boyle Dam on the Klamath River in the U.S. state of Oregon. The lake is 16 miles (26 km) west-southwest of Klamath Falls along Oregon Route 66.

The Klamath Basin Restoration Agreement (KBRA) is an American multi-party legal agreement determining river usage and water rights involving the Klamath River and Klamath Basin in the states of California and Oregon. Discussion of the KBRA began in 2005. Congress failed to pass legislation that would implement the KBRA by the January 1, 2016 deadline.

The Klamath River Hydroelectric Project is a series of hydroelectric dams and other facilities on the mainstem of the Klamath River, in a watershed on both sides of the California-Oregon border.

Blue Creek is a 23-mile (37 km) long stream in the Northern Coast Ranges of California, and is the lowermost major tributary of the Klamath River. The creek begins in Elk Valley, in the Siskiyou Wilderness of the Six Rivers National Forest in Del Norte County. It flows southwest, receiving several major tributaries including the East Fork, Crescent City Fork, Nickowitz Creek, Slide Creek and the West Fork. It flows into the Klamath River in Humboldt County, 16 miles (26 km) upstream from where the Klamath empties into the Pacific Ocean.