Rural flight is the migratory pattern of people from rural areas into urban areas. It is urbanization seen from the rural perspective.

Unemployment, according to the OECD, is people above a specified age not being in paid employment or self-employment but currently available for work during the reference period.

Full employment is a situation in which there is no cyclical or deficient-demand unemployment. Full employment does not entail the disappearance of all unemployment, as other kinds of unemployment, namely structural and frictional, may remain. For instance, workers who are "between jobs" for short periods of time as they search for better employment are not counted against full employment, as such unemployment is frictional rather than cyclical. An economy with full employment might also have unemployment or underemployment where part-time workers cannot find jobs appropriate to their skill level, as such unemployment is considered structural rather than cyclical. Full employment marks the point past which expansionary fiscal and/or monetary policy cannot reduce unemployment any further without causing inflation.

Frictional unemployment is a form of unemployment reflecting the gap between someone voluntarily leaving a job and finding another. As such, it is sometimes called search unemployment, though it also includes gaps in employment when transferring from one job to another.

The labor force in Japan numbered 65.9 million people in 2010, which was 59.6% of the population of 15 years old and older, and amongst them, 62.57 million people were employed, whereas 3.34 million people were unemployed which made the unemployment rate 5.1%. The structure of Japan's labor market experienced gradual change in the late 1980s and continued this trend throughout the 1990s. The structure of the labor market is affected by: 1) shrinking population, 2) replacement of postwar baby boom generation, 3) increasing numbers of women in the labor force, and 4) workers' rising education level. Also, an increase in the number of foreign nationals in the labor force is foreseen.

Social issues in China are wide-ranging, and are a combined result of Chinese economic reforms set in place in the late 1970s, the nation's political and cultural history, and an immense population. Due to the significant number of social problems that have existed throughout the country, China's government has faced difficulty in trying to remedy the issues. Many of these issues are exposed by the Chinese media, while subjects that may contain politically sensitive issues may be censored. Some academics hold that China's fragile social balance, combined with a bubble economy makes China a very unstable country, while others argue China's societal trends have created a balance to sustain itself.

Graduate unemployment, or educated unemployment, is unemployment among people with an academic degree.

Active labour market policies (ALMPs) are government programmes that intervene in the labour market to help the unemployed find work, but also for the underemployed and employees looking for better jobs. In contrast, passive labour market policies involve expenditures on unemployment benefits and early retirement. Historically, labour market policies have developed in response to both market failures and socially/politically unacceptable outcomes within the labor market. Labour market issues include, for instance, the imbalance between labour supply and demand, inadequate income support, shortages of skilled workers, or discrimination against disadvantaged workers.

Internal migration in the People's Republic of China is one of the most extensive in the world according to the International Labour Organization. This is because migrants in China are commonly members of a floating population, which refers primarily to migrants in China without local household registration status through the Chinese Hukou system. In general, rural-urban migrant most excluded from local educational resources, citywide social welfare programs and many jobs because of their lack of hukou status. Migrant workers are not necessarily rural workers; they can simply be people living in urban areas with rural household registration.

A job guarantee is an economic policy proposal that aims to create full employment and price stability by having the state promise to hire unemployed workers as an employer of last resort (ELR). It aims to provide a sustainable solution to inflation and unemployment.

As the economy of China has rapidly developed, issues of labor relations have evolved. Prior to this reform, Chinese citizens were only allowed to work where they originated from. Since 1978, when China began labor force reforms, the overwhelming majority of the labor force were either working at State owned enterprises or as farm workers in the rural countryside. However, over time China began to reform and by the late 90's many had moved from the countryside into the cities in hopes of higher paying jobs and more opportunities. The only connection between the countryside and the city soon became that there was a huge floating population connecting them. Independent unions are illegal in China with only the All-China Federation of Trade Unions (ACTFU) permitted to operate. China has been the largest exporter of goods in the world since 2009. Not only that, in 2013 China became the largest trading nation in the world. As China moved away from their planned economy and more towards a market economy the government has brought on many reforms. The aim of this shift in economies was to match the international standards set by the World Trade Organization and other economic entities. The ACTFU that was established to protect the interests of national and local trade unions failed to represent the workers, but instead failed to do so leading to the 2010 crackdowns. However, these strikes were centered around foreign companies.

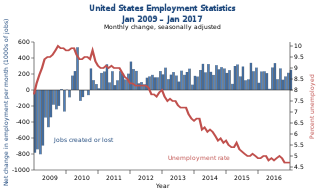

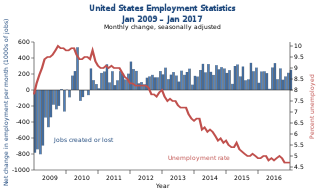

Unemployment in the United States discusses the causes and measures of U.S. unemployment and strategies for reducing it. Job creation and unemployment are affected by factors such as economic conditions, global competition, education, automation, and demographics. These factors can affect the number of workers, the duration of unemployment, and wage levels.

An economic recovery is the phase of the business cycle following a recession. The overall business outlook for an industry looks optimistic during the economic recovery phase.

Youth unemployment is a special case of unemployment; youth, here, meaning those between the ages of 15 and 24.

Statistics on unemployment in India had traditionally been collected, compiled and disseminated once every ten years by the Ministry of Labour and Employment (MLE), primarily from sample studies conducted by the National Sample Survey Office. Other than these 5-year sample studies, India has – except since 2017 – never routinely collected monthly, quarterly or yearly nationwide employment and unemployment statistics. In 2016, the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy, a non-governmental entity based in Mumbai, started sampling and publishing monthly unemployment in India statistics.

Job creation and unemployment are affected by factors such as aggregate demand, global competition, education, automation, and demographics. These factors can affect the number of workers, the duration of unemployment, and wage rates.

Youth unemployment in Italy discusses the statistics, trends, causes and consequences of unemployment among young Italians. Italy displays one of the highest rates of youth unemployment among the 35 member countries of the Organization of Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). The Italian youth unemployment rate started raising dramatically since the 2008 financial crisis reaching its peak of 42.67% in 2014. In 2017, among the EU member states, the youth unemployment rate of Italy (35.1%) was exceeded by only Spain and Greece. The Italian youth unemployment rate was more than the double of the total EU average rate of 16.7% in 2017. While youth unemployment is extremely high compared to EU standards, the Italian total unemployment rate (11.1%) is closer to EU average (7.4%).

The rate of youth unemployment in South Korea fluctuated in the 9–11% range between 2001 and 2014. It was above 10% in 2018 and down to 7.1% by the end of 2019 - the lowest level since 2011.

Active labour market policies are actions that governments take to help the unemployed back into work. In South Korea, they are administered under the direct supervision of the Ministry of Labor and Employment. They involve subsidized education, vocational training, direct monetary support, and low interest loans.

Academic job market in Ethiopia is under development in every higher education institution. The government of Ethiopia is improving the quality of employment for university graduate students to achieve favorable market system and reduce poverty. This, however, obstructed by shortage of skilled manpower as higher education institutions produce graduate students every year.