Double jeopardy is a procedural defence that prevents an accused person from being tried again on the same charges and on the same facts, following a valid acquittal or conviction. As described by the U.S. Supreme Court in its unanimous decision concerning Ball v. United States 163 U.S. 662 (1896), one of its earliest cases dealing with double jeopardy, "the prohibition is not against being twice punished, but against being twice put in jeopardy; and the accused, whether convicted or acquitted, is equally put in jeopardy at the first trial."

Apprendi v. New Jersey, 530 U.S. 466 (2000), is a landmark United States Supreme Court decision with regard to aggravating factors in crimes. The Court ruled that the Sixth Amendment right to a jury trial, incorporated against the states through the Fourteenth Amendment, prohibited judges from enhancing criminal sentences beyond statutory maxima based on facts other than those decided by the jury beyond a reasonable doubt. The decision has been a cornerstone in the modern resurgence in jury trial rights. As Justice Scalia noted in his concurring opinion, the jury-trial right "has never been efficient; but it has always been free."

Gregg v. Georgia, Proffitt v. Florida, Jurek v. Texas, Woodson v. North Carolina, and Roberts v. Louisiana, 428 U.S. 153 (1976), reaffirmed the United States Supreme Court's acceptance of the use of the death penalty in the United States, upholding, in particular, the death sentence imposed on Troy Leon Gregg. Referred to by a leading scholar as the July 2 Cases and elsewhere referred to by the lead case Gregg, the Supreme Court set forth the two main features that capital sentencing procedures must employ in order to comply with the Eighth Amendment ban on "cruel and unusual punishments". The decision essentially ended the de facto moratorium on the death penalty imposed by the Court in its 1972 decision in Furman v. Georgia 408 U.S. 238 (1972).

Roper v. Simmons, 543 U.S. 551 (2005), was a landmark decision in which the Supreme Court of the United States held that it is unconstitutional to impose capital punishment for crimes committed while under the age of 18. The 5–4 decision overruled Stanford v. Kentucky, in which the court had upheld execution of offenders at or above age 16, and overturned statutes in 25 states.

Robinson v. California, 370 U.S. 660 (1962), is the first decision of the United States Supreme Court in which the Eighth Amendment of the Constitution was interpreted to prohibit criminalization of particular acts or conduct, as contrasted with prohibiting the use of a particular form of punishment for a crime. In Robinson, the Court struck down a California law that criminalized being addicted to narcotics.

The People of the State of California v. Robert Page Anderson, 493 P.2d 880, 6 Cal. 3d 628, was a landmark case in the state of California that outlawed the use of capital punishment. It was subsequently overruled by a state constitutional amendment, called Proposition 17.

Harmelin v. Michigan, 501 U.S. 957 (1991), was a case decided by the Supreme Court of the United States under the Eighth Amendment to the United States Constitution. The Court ruled that the Eighth Amendment's Cruel and Unusual Punishment Clause allowed a state to impose a life sentence without the possibility of parole for the possession of 672 grams of cocaine.

Weems v. United States, 217 U.S. 349 (1910), was a decision of the United States Supreme Court. It is primarily notable as it pertains to the prohibition of cruel and unusual punishment. It is cited concerning the political and legal relationship between the United States and the Philippines, which at that time was considered a U.S. colony.

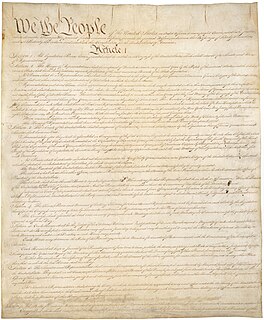

The Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution addresses criminal procedure and other aspects of the Constitution. It was ratified in 1791 as part of the Bill of Rights. The Fifth Amendment applies to every level of the government, including the federal, state, and local levels, as well as any corporation, private enterprise, group, or individual, or any foreign government in regards to a US citizen or resident of the US. The Supreme Court furthered the protections of this amendment through the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

In criminal law, a mitigating factor, also known as extenuating circumstances, is any information or evidence presented to the court regarding the defendant or the circumstances of the crime that might result in reduced charges or a lesser sentence. Unlike a legal defense, it cannot lead to the acquittal of the defendant. The opposite of a mitigating factor is an aggravating factor.

Tennard v. Dretke, 542 U.S. 274 (2004), was a United States Supreme Court case in which the court was asked whether evidence of the defendant's low IQ in a death penalty trial had been adequately presented to the jury for full consideration in the penalty phase of his trial. The Supreme Court held that not considering a defendant's low IQ would breach his Eighth Amendment rights and constitute a cruel and unusual punishment.

Heath v. Alabama, 474 U.S. 82 (1985), is a case in which the United States Supreme Court ruled that, because of the doctrine of "dual sovereignty", the double jeopardy clause of the Fifth Amendment to the Constitution does not prohibit one state from prosecuting and punishing somebody for an act of which they had already been convicted of and sentenced for in another state.

United States criminal procedure derives from several sources of law: the baseline protections of the United States Constitution, federal and state statutes; federal and state rules of criminal procedure ; and state and federal case law. Criminal procedures are distinct from civil procedures in the US.

The Double Jeopardy Clause of the Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution provides: "[N]or shall any person be subject for the same offence to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb..." The four essential protections included are prohibitions against, for the same offense:

Griffin v. California, 380 U.S. 609 (1965), was a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court ruled, by a 6-2 vote, that it is a violation of a defendant's Fifth Amendment rights for the prosecutor to comment to the jury on the defendant's declining to testify, or for the judge to instruct the jury that such silence is evidence of guilt.

The United States Constitution contains several provisions regarding the law of criminal procedure.

The Taney Court heard thirty criminal law cases, approximately one per year. Notable cases include Prigg v. Pennsylvania (1842), United States v. Rogers (1846), Ableman v. Booth (1858), Ex parte Vallandigham (1861), and United States v. Jackalow (1862).

The Crimes Act of 1790, formally titled An Act for the Punishment of Certain Crimes Against the United States, defined some of the first federal crimes in the United States and expanded on the criminal procedure provisions of the Judiciary Act of 1789. The Crimes Act was a "comprehensive statute defining an impressive variety of federal crimes."