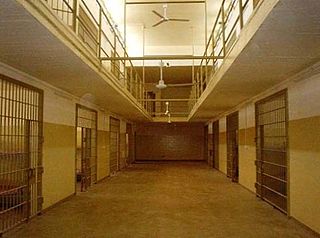

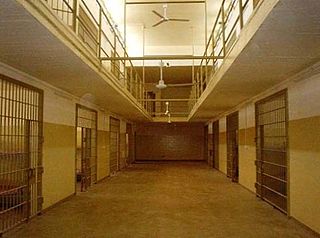

Abu Ghraib prison was a prison complex in Abu Ghraib, Iraq, located 32 kilometers (20 mi) west of Baghdad. Abu Ghraib prison was opened in the 1950s and served as a maximum-security prison. From the 1970s, the prison was used by Saddam Hussein to hold political prisoners and later the United States to hold Iraqi prisoners. It developed a reputation for torture and extrajudicial killing, and was closed in 2014.

Camp Bucca was a forward operating base that housed a theater internment facility maintained by the United States military in the vicinity of Umm Qasr, Iraq. After being taken over by the U.S. military in April 2003, it was renamed after Ronald Bucca, a New York City fire marshal who died in the 11 September 2001 attacks. The site where Camp Bucca was built had earlier housed the tallest structure in Iraq, a 492-meter-high TV mast.

During the early stages of the Iraq War, members of the United States Army and the Central Intelligence Agency committed a series of human rights violations and war crimes against detainees in the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq, including physical abuse, sexual humiliation, physical and psychological torture, and rape, as well the killing of Manadel al-Jamadi and the desecration of his body. The abuses came to public attention with the publication of photographs of the abuse by CBS News in April 2004. The incidents caused shock and outrage, receiving widespread condemnation within the United States and internationally.

About six months after the United States invasion of Iraq of 2003, rumors of Iraq prison abuse scandals started to emerge.

Camp Cropper was a holding facility for security detainees operated by the United States Army near Baghdad International Airport in Iraq. The facility was initially operated as a high-value detention site (HVD), but has since been expanded increasing its capacity from 163 to 2,000 detainees. Former Iraqi President Saddam Hussein was held there prior to his execution. Mr. Hussein was held at a nearby location outside the Camp Cropper complex. He was isolated from the former Ba'ath Party and subsequent HVT’s held at the main Cropper facility.

Geoffrey D. Miller is a retired United States Army major general who commanded the US detention facilities at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, and Iraq. Detention facilities in Iraq under his command included Abu Ghraib prison, Camp Cropper, and Camp Bucca. He is noted for having trained soldiers in using torture, or "enhanced interrogation techniques" in US euphemism, and for carrying out the "First Special Interrogation Plan," signed by the Secretary of Defense, against a Guantanamo detainee.

A high-value detention site or HVD, in current U.S. military parlance, is a prison for those who may have valuable intelligence to offer, or who have inherent military or political significance. An example is former Iraqi president Saddam Hussein, as well as senior members of his regime. Other prisoners of these sites include members of Al-Qaeda, captured during the War on Terrorism.

Ghost detainee is a term used in the executive branch of the United States government to designate a person held in a detention center, whose identity has been hidden by keeping them unregistered and therefore anonymous. Such uses arose as the Bush administration initiated the War on Terror following the 9/11 attacks of 2001 in the United States. As documented in the 2004 Taguba Report, it was used in the same manner by United States officials and contractors of the Joint Interrogation and Debriefing Center at the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq in 2003–2004.

Extrajudicial prisoners of the United States, in the context of the early twenty-first century War on Terrorism, refers to foreign nationals the United States detains outside of the legal process required within United States legal jurisdiction. In this context, the U.S. government is maintaining torture centers, called black sites, operated by both known and secret intelligence agencies. Such black sites were later confirmed by reports from journalists, investigations, and from men who had been imprisoned and tortured there, and later released after being tortured until the CIA was comfortable they had done nothing wrong, and had nothing to hide.

The Battle of Abu Ghraib took place between Iraqi Mujahideen and United States forces at Abu Ghraib prison on April 2, 2005.

Abu Omar al-Baghdadi, born Hamid Dawud Mohamed Khalil al-Zawi was the Emir of the Islamic militant umbrella organization Mujahideen Shura Council (MSC), and its successor, the Islamic State of Iraq (ISI), which fought against the U.S.-led Coalition forces during the Iraqi insurgency.

Fort Suse is an Iraqi military installation located in the Kurdistan region of Iraq in the vicinity of Al-Sulamaniya. It was built in 1977 by Russian engineers as a barracks and training facility, but now serves as a prison.

During the Iraq War, many insurgents, al-Qaeda and militant fighters were captured and held at military bases in the region. On several occasions, there were instances of prisoner escapes.

A number of incidents stemming from the September 11 attacks have raised questions about legality.

Neaman Salman Mansour al-Zaidi, known as Abu Suleiman al-Naser, was the military commander or "War Minister" of the militant group Islamic State of Iraq (ISI) during the Iraq War.

Shaker Wahib al-Fahdawi al-Dulaimi, better known as Abu Waheeb, was a leader of the Islamic State in Anbar, Iraq. He killed three Syrian truck drivers in Iraq in the summer of 2013, and was himself killed, with three others, in a United States-led coalition airstrike in May 2016, according to the US Department of Defense.

Ahmed Hussein al-Shar’a, known by the nom de guerreAbu Mohammad al-Julani, is the commander-in-chief of the Syrian militant group Tahrir al-Sham.

Adnan Ismail Najm al-Bilawi Al-Dulaimi, better known by the nom de guerre Abu Abdulrahman al-Bilawi al-Anbari, was a top commander in the Islamic State and the head of its Military Council, prior to his killing by Iraqi security forces on 4 June 2014.

Adnan Latif Hamid al-Suwaydawi al-Dulaymi, also known by his noms de guerre Abu Muhannad al-Suwaydawi, Abu Abdul Salem, and Haji Dawūd was a top commander in the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) and the former head of its Military Council.

The origins of the Islamic State group can be traced back to three main organizations. Earliest of these was the "Jamāʻat al-Tawḥīd wa-al-Jihād" organization, founded by the Jihadist leader Abu Mus'ab al-Zarqawi in Jordan in 1999. The other two predecessor organizations emerged during the Iraqi insurgency against the U.S. occupation forces. These included the "Jaish al-Ta'ifa al-Mansurah" group founded by Abu Omar al-Baghdadi in 2004 and the "Jaysh Ahl al-Sunnah wa’l-Jama’ah" group founded by Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi and his associates in the same year.