A cluster munition is a form of air-dropped or ground-launched explosive weapon that releases or ejects smaller submunitions. Commonly, this is a cluster bomb that ejects explosive bomblets that are designed to kill personnel and destroy vehicles. Other cluster munitions are designed to destroy runways or electric power transmission lines, disperse chemical or biological weapons, or to scatter land mines. Some submunition-based weapons can disperse non-munitions, such as leaflets.

The BM-30 Smerch, 9K58 Smerch or 9A52-2 Smerch-M is a heavy self-propelled 300 mm multiple rocket launcher designed in the Soviet Union to fire a full load of 12 solid-fuelled projectiles. The system is intended to defeat personnel, armored, and soft targets in concentration areas, artillery batteries, command posts and ammunition depots. It was designed in the early 1980s and entered service in the Soviet Army in 1989. When first observed by the West in 1983, it received the code MRL 280mm M1983. It continues in use by Russia; a program to replace it with the 9A52-4 Tornado began in 2018.

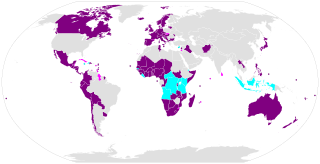

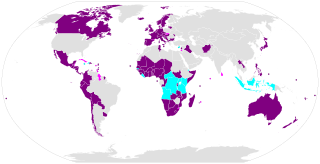

The Convention on Cluster Munitions (CCM) is an international treaty that prohibits all use, transfer, production, and stockpiling of cluster bombs, a type of explosive weapon which scatters submunitions ("bomblets") over an area. Additionally, the convention establishes a framework to support victim assistance, clearance of contaminated sites, risk reduction education, and stockpile destruction. The convention was adopted on 30 May 2008 in Dublin, and was opened for signature on 3 December 2008 in Oslo. It entered into force on 1 August 2010, six months after it was ratified by 30 states. As of February 2022, a total of 123 states are committed to the goal of the convention, with 110 states that have ratified it, and 13 states that have signed the convention but not yet ratified it.

Colonel General Alexander Alexandrovich Zhuravlyov is a Russian Ground Forces officer who has commanded the military force in Syria during the Russian military intervention in the Syrian Civil War and served as the commander of the Western Military District from November 2018 to June 2022. After returning from Syria, he became the Deputy Chief of the General Staff before being appointed commander of the Eastern Military District in November 2017. He was also awarded the title Hero of the Russian Federation in 2016 by a directive of the President. Currently, Western nations have identified him as a war criminal in Ukraine, and have imposed sanctions on him.

Instalaza SA is a Spanish firm that designs, develops and manufactures equipment and other military material for infantry. The company, founded in 1943, is headquartered in Zaragoza, Aragon, where its production plant is also located.

During the ongoing Russo-Ukrainian War between the Ukrainian government forces and pro-Russian separatists in the Donbas region of Ukraine that began in April 2014, many international organisations and states noted a deteriorating humanitarian situation in the conflict zone.

Russian war crimes since 1991 are the violations of the law of war, including the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907 and the Geneva Conventions, consisting of war crimes, crimes against humanity, and the crime of genocide, which the official armed and paramilitary forces of the Russian Federation have been accused of committing since the dissolution of the Soviet Union. This accusation also extends to the aiding and abetting of crimes which have been committed by quasi-states or puppet states which are armed and financed by Russia, including the Luhansk People's Republic and the Donetsk People's Republic. These war crimes have included murder, torture, terrorism, deportation or forced transfer, abduction, looting, unlawful confinement, unlawful airstrikes or attacks against civilian objects, and rape.

Casualties in the Russo-Ukrainian War included six deaths during the 2014 annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation, 14,200–14,400 civilians and military troops killed during the War in Donbas (2014–2022), and tens of thousands of deaths during the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine.

The bombardment of Stepanakert began on September 27, 2020, the first day of the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war, and lasted throughout the duration of the war. Stepanakert is the capital and largest city of the self-proclaimed Republic of Artsakh, internationally recognized as part of Azerbaijan, and was home to 60,000 Armenians on the eve of the war. Throughout the 6-week bombardment, international third parties consistently confirmed evidence of the indiscriminate use of cluster bombs and missiles by Azerbaijan against civilian areas lacking any military installations in Stepanakert; this was denied by Azerbaijan. The prolonged bombardment forced many residents to flee, and the rest to take cover in crowded bomb shelters, leading to a severe outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in the city, infecting a majority of the remaining residents. Throughout the course of the bombardment, 13 residents were killed, 51 were injured, and 4,258 buildings in the city were damaged.

The Barda missile attacks was a series of three air attacks on the city of Barda, as well as the villages of Əyricə and Qarayusifli in the same district, in Azerbaijan during the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war. The attacks involved BM-30 Smerch missiles with cluster warheads, and resulted in 27 civilian deaths.

Since the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, Russian authorities and armed forces have committed multiple war crimes in the form of deliberate attacks against civilian targets, massacres of civilians, torture and rape of women and children, and indiscriminate attacks in densely populated areas.

The battle of Okhtyrka was a military engagement in and around Okhtyrka city in Sumy Oblast of Ukraine. It began on 24 February 2022, as part of the Northeastern Ukraine offensive during the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine. Fighting began in the outskirts of the city as Russian forces attempted to occupy the city. The initial advance was repelled, and the city was attacked by artillery fire. On March 26, 2022, it was reported that the strategic stronghold of Trostianets was taken back by Ukrainian Forces. This disrupted Russian communications and supply routes, threatening the Russian front.

On 14 March 2022, during the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, a Tochka-U missile attack hit the center of Donetsk, Ukraine, at the time under Russian occupation and administration of the Donetsk People's Republic (DPR). The Russian Investigative Committee reported that the attack killed 23 civilians, including children, and injured at least 18 people. The Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights reported that the attacked killed 15 civilians and injured 36 people. Ukraine claimed that the rocket had been fired by the Russians, while Russia and the DPR claimed that the attack was carried out by Ukrainian forces. As of 14 March, neither the Russian nor the Ukrainian claims could be independently verified.

On 13 March 2022, during the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, Russian Armed Forces bombed Mykolaiv with cluster munitions, killing nine civilians.

The battle of Avdiivka is an ongoing military engagement between the Russian Armed Forces and Donbas Separatist Forces on one side and the Ukrainian Armed Forces on the other. It is being fought over the city of Avdiivka, located in the Donbas region. Fighting started when violence erupted in the Donbas again on 21 February 2022, when Russian president Vladimir Putin recognized the Donetsk People's Republic. Days later, when Russia invaded Ukraine, Avdiivka was among the first places to be attacked.

On February 28, 2022, a series of rocket strikes by the Russian Armed Forces killed 9 civilians and wounded 37 more during the battle of Kharkiv, part of the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine. The Russian Army used cluster munition in the attack. Due to the indiscriminate nature of these weapons used in densely populated areas, Human Rights Watch described these strikes as a possible war crime.

On 8 April 2022, a Russian missile strike hit the railway station of the Ukrainian city of Kramatorsk during the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The strike killed 60 civilians and wounded more than 110. Russian authorities denied responsibility and blamed the attack on Ukraine.

During the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Russia used white phosphorus bombs in the battles for Kyiv and Kramatorsk in March, against defenders at the Azovstal steel plant in Mariupol in May, and in many different locations over the 2022 Christmas holiday. In turn, the Russian Ministry of Defense claimed that the armed forces of Ukraine used phosphorus ammunition in the defense of the Hostomel airfield at the end of February.

The battle of Marinka is an ongoing battle taking place in the city of Marinka between the Armed Forces of Russia and the separatist Donetsk People's Republic against the Armed Forces of Ukraine. Shelling of the town intensified between 17 February and 22 February 2022, when Russia recognized the DPR as independent, and fighting began in the town on 17 March.

During the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, Russian authorities and armed forces have committed war crimes by carrying out deliberate attacks against civilian targets and indiscriminate attacks in densely populated areas. The Russian military exposed the civilian population to unnecessary and disproportionate harm by using cluster munitions and by firing other explosive weapons with wide-area effects such as bombs, missiles, heavy artillery shells and multiple launch rockets.