A mummy is a dead human or an animal whose soft tissues and organs have been preserved by either intentional or accidental exposure to chemicals, extreme cold, very low humidity, or lack of air, so that the recovered body does not decay further if kept in cool and dry conditions. Some authorities restrict the use of the term to bodies deliberately embalmed with chemicals, but the use of the word to cover accidentally desiccated bodies goes back to at least the early 17th century.

Saqqara, also spelled Sakkara or Saccara in English, is an Egyptian village in the markaz (county) of Badrashin in the Giza Governorate, that contains ancient burial grounds of Egyptian royalty, serving as the necropolis for the ancient Egyptian capital, Memphis. Saqqara contains numerous pyramids, including the Pyramid of Djoser, sometimes referred to as the Step Tomb, and a number of mastaba tombs. Located some 30 km (19 mi) south of modern-day Cairo, Saqqara covers an area of around 7 by 1.5 km.

A bog body is a human cadaver that has been naturally mummified in a peat bog. Such bodies, sometimes known as bog people, are both geographically and chronologically widespread, having been dated to between 8000 BCE and the Second World War. The unifying factor of the bog bodies is that they have been found in peat and are partially preserved; however, the actual levels of preservation vary widely from perfectly preserved to mere skeletons.

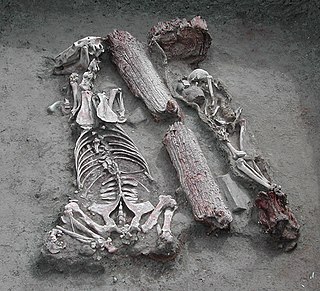

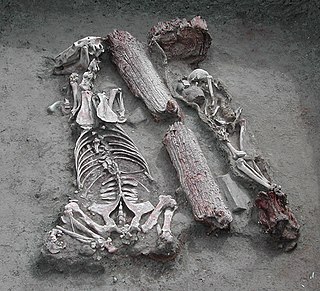

The Pazyrykburials are a number of Scythian (Saka) Iron Age tombs found in the Pazyryk Valley and the Ukok plateau in the Altai Mountains, Siberia, south of the modern city of Novosibirsk, Russia; the site is close to the borders with China, Kazakhstan and Mongolia.

The Rosicrucian Egyptian Museum (REM) is devoted to ancient Egypt, located at Rosicrucian Park in the Rose Garden neighborhood of San Jose, California, United States.

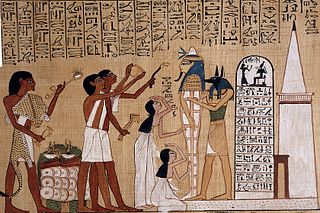

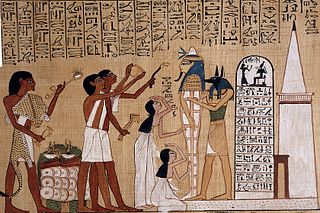

The ancient Egyptians had an elaborate set of funerary practices that they believed were necessary to ensure their immortality after death. These rituals included mummifying the body, casting magic spells, and burials with specific grave goods thought to be needed in the afterlife.

Tomb KV60 is an ancient Egyptian tomb in the Valley of the Kings, Egypt. It was discovered by Howard Carter in 1903, and re-excavated by Donald P. Ryan in 1989. It is one of the more perplexing tombs of the Theban Necropolis, due to the uncertainty over the identity of one female mummy found there (KV60A). She is identified by some, such as Egyptologist Elizabeth Thomas, to be that of the Eighteenth Dynasty pharaoh Hatshepsut; this identification is advocated for by Zahi Hawass.

The Royal Cache, technically known as TT320, is an Ancient Egyptian tomb located next to Deir el-Bahari, in the Theban Necropolis, opposite the modern city of Luxor.

Thuya was an Egyptian noblewoman and the mother of queen Tiye, and the wife of Yuya. She is the grandmother of Akhenaten, and great grandmother of Tutankhamun.

The Chinchorro mummies are mummified remains of individuals from the South American Chinchorro culture, found in what is now northern Chile. They are the oldest examples of artificially mummified human remains, having been buried up to two thousand years before the Egyptian mummies. The earliest mummy that has been found in Egypt dated around 3000 BCE, while the oldest anthropogenically modified Chinchorro mummy dates from around 5050 BCE.

The Saltmen were discovered in the Chehrabad salt mines, located on the southern part of the Hamzehlu village, on the west side of the city of Zanjan, in the Zanjan Province in Iran. By 2010, the remains of six men had been discovered, most of them accidentally killed by the collapse of galleries in which they were working. The head and left foot of Salt Man 1 are on display at the National Museum of Iran in Tehran.

Takabuti was a married woman who reached an age of between twenty and thirty years. She lived in the Egyptian city of Thebes at the end of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt. Her mummified body and mummy case are in the Ulster Museum in Belfast.

The Gebelein predynastic mummies are six naturally mummified bodies, dating to approximately 3400 BC from the Late Predynastic period of Ancient Egypt. They were the first complete predynastic bodies to be discovered. The well-preserved bodies were excavated at the end of the nineteenth century by Wallis Budge, the British Museum Keeper for Egyptology, from shallow sand graves near Gebelein in the Egyptian desert.

Animal mummification was common in ancient Egypt. Animals were an important part of Egyptian culture, not only in their role as food and pets, but also for religious reasons. Many different types of animals were mummified, typically for four main purposes: to allow people's beloved pets to go on to the afterlife, to provide food in the afterlife, to act as offerings to a particular god, and because some were seen as physical manifestations of specific deities that the Egyptians worshipped. Bastet, the cat goddess, is an example of one such deity. In 1888, an Egyptian farmer digging in the sand near Istabl Antar discovered a mass grave of felines, ancient cats that were mummified and buried in pits at great numbers.

An intramedullary rod, also known as an intramedullary nail or inter-locking nail or Küntscher nail, is a metal rod forced into the medullary cavity of a bone. IM nails have long been used to treat fractures of long bones of the body. Gerhard Küntscher is credited with the first use of this device in 1939, during World War II, for soldiers with fractures of the femur. Prior to that, treatment of such fractures was limited to traction or plaster, both of which required long periods of inactivity. IM nails resulted in earlier return to activity for the soldiers, sometimes even within a span of a few weeks, since they share the load with the bone, rather than entirely supporting the bone.

Tutankhamun's mummy was discovered by English Egyptologist Howard Carter and his team on 28 October 1925 in tomb KV62 of Egypt's Valley of the Kings. Tutankhamun was the 13th pharaoh of the 18th Dynasty of the New Kingdom of Egypt, making his mummy over 3,300 years old. Tutankhamun's mummy is the only royal mummy to have been found entirely undisturbed.

Xin Zhui, also known as Lady Dai or the Marquise of Dai, was a Chinese noblewoman. She was the wife of Li Cang (利蒼), the Marquis of Dai, and Chancellor of the Changsha Kingdom, during the Western Han dynasty of ancient China. Her tomb, containing her well-preserved remains and 1,400 artifacts, was discovered in 1971 at Mawangdui, Changsha, Hunan, China. Her body and belongings are currently under the care of the Hunan Museum; artifacts from her tomb were displayed in Santa Barbara and New York City in 2009. Her body is notable as being one of the most well preserved mummies ever found.

Fagg El Gamous is an ancient Egyptian cemetery located in the Faiyum Governorate dating from the 1st to the 7th century AD, the period of Roman rule in Egypt.

Mummies 317a and 317b were the infant daughters of the ancient Egyptian pharaoh Tutankhamun of the Eighteenth Dynasty. Their mother is presumed to be Ankhesenamun, his only known wife, who has been tentatively identified through DNA testing as the mummy KV21A. 317a was born prematurely at 5–6 months' gestation, and 317b was born at or near full term. They are assumed to have been stillborn or died shortly after birth.

The archaeology of Ancient Egypt is the study of the archaeology of Egypt, stretching from prehistory through three millennia of documented history. Egyptian archaeology is one of the branches of Egyptology.