Mass media in India consists of several different means of communication: television, radio, cinema, newspapers, magazines, and Internet-based websites/portals. Indian media was active since the late 18th century. The print media started in India as early as 1780. Radio broadcasting began in 1927. Today much of the media is controlled by large, corporations, which reap revenue from advertising, subscriptions, and sale of copyrighted material.

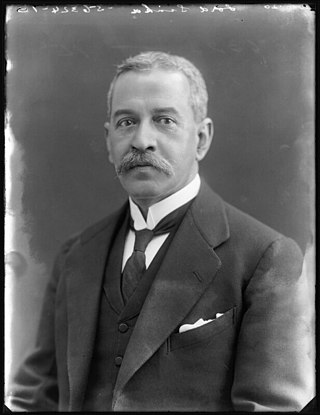

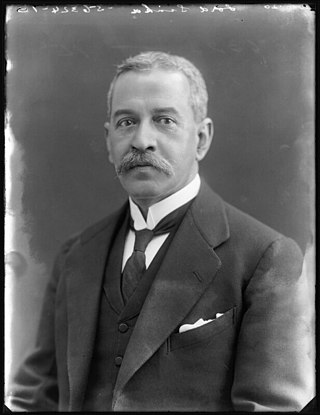

Satyendra Prasanna Sinha, 1st Baron Sinha, KCSI, PC, KC, was a prominent British Indian lawyer and statesman. He was the first Governor of Bihar and Orissa, first Indian Advocate-General of Bengal, first Indian to become a member of the Viceroy's Executive Council and the first Indian to become a member of the British ministry. He is sometimes also referred as Satyendra Prasanno Sinha or Satyendra Prasad Sinha.

Anandabazar Patrika is an Indian Bengali-language daily newspaper owned by the ABP Group. Its main competitors are Bartaman, Ei Samay, and Sangbad Pratidin.

Claims of media bias in South Asia attract constant attention. The question of bias in South Asian media is also of great interest to people living outside of South Asia. Some accusations of media bias are motivated by a disinterested desire for truth, some are politically motivated. Media bias occurs in television, newspapers, school books and other media.

Anushilan Samiti was an Indian fitness club, which was actually used as an underground society for anti-British revolutionaries. In the first quarter of the 20th century it supported revolutionary violence as the means for ending British rule in India. The organisation arose from a conglomeration of local youth groups and gyms (akhara) in Bengal in 1902. It had two prominent, somewhat independent, arms in East and West Bengal, Dhaka Anushilan Samiti, and the Jugantar group.

Tushar Kanti Ghosh was an Indian journalist and writer. For sixty years, until shortly before his death, Ghosh was the editor of the English-language newspaper Amrita Bazar Patrika in Kolkata. He also served as the leader of prominent journalism organizations such as the International Press Institute and the Commonwealth Press Union. Ghosh was known as the "grand old man of Indian journalism" and "the dean of Indian journalism" for his contributions to the country's free press.

The Press Act of 1908 was legislation promulgated in British India imposing strict censorship on all kinds of publications. The measure was brought into effect to curtail the influence of Indian vernacular and English language in promoting support for what was considered radical Indian nationalism. this act gave the British rights to imprison and execute anyone who writes radical articles in the newspapers. It followed in the wake of two decades of increasing influence of journals such as Kesari in Western India, publications such as Jugantar and Bandemataram in Bengal, and similar journals emerging in the United Provinces. These were deemed to influence a surge in nationalist violence and revolutionary terrorism against interests and officials of the Raj in India, particularly in Maharashtra and in Bengal. A widespread influence was noted amongst the general population which drew a large proportion population of youth towards the ideology of radical nationalists such as Bal Gangadhar Tilak and Aurobindo Ghosh, and towards secret revolutionary organisations such as Anushilan Samiti in Bengal and Mitra Mela in Maharashtra. This peaked in 1908, with the attempted assassination of a local judge in Bengal, and a number of assassinations of local Raj officials in Maharshtra. The aftermath of Muzaffarpur bombings saw Tilak convicted on charges of sedition, while in Bengal a large number of nationalists of the Anushilan Samiti were convicted. However, Aurobindo Ghosh had escaped conviction. With defiant messages from journals such as Jugantar, the propvisions of the 1878 Vernacular Press Act were revived. Herbert Hope Risley, in 1907, declared, "We are overwhelmed with a mass of heterogeneous material, some of it misguided, some of it frankly seditious," in response to a deluge of imagery associated with the Cow Protection Movement. These concerns led him to draft the major substance of the 1910 Press Act.

Amrita Bazar Patrika was one of the oldest daily newspapers in India. Originally published in Bengali script, it evolved into an English format published from Kolkata and other locations such as Cuttack, Ranchi and Allahabad. The paper discontinued its publication in 1991 after 123 years of publication. Its sister newspaper was the Bengali-language daily newspaper Jugantar, which remained in circulation from 1937 till 1991.

The Barisal Conspiracy Case of 1913 was a trial prosecuted by the British colonial authorities against 44 Bengalis who were accused of planning to incite rebellion against the Raj and associated leaders were Trailokyanath Chakravarty and Pratul Chandra Ganguli. As such, it was part of the greater movement for independence that swept India in the decades prior to the departure of the British in 1947.

The Defence of India Act 1915, also referred to as the Defence of India Regulations Act, was an emergency criminal law enacted by the Governor-General of India in 1915 with the intention of curtailing the nationalist and revolutionary activities during and in the aftermath of the First World War. It was similar to the British Defence of the Realm Acts, and granted the Executive very wide powers of preventive detention, internment without trial, restriction of writing, speech, and of movement. However, unlike the English law which was limited to persons of hostile associations or origin, the Defence of India act could be applied to any subject of the King, and was used to an overwhelming extent against Indians. The passage of the act was supported unanimously by the non-official Indian members in the Viceroy's legislative council, and was seen as necessary to protect against British India from subversive nationalist violence. The act was first applied during the First Lahore Conspiracy trial in the aftermath of the failed Ghadar Conspiracy of 1915, and was instrumental in crushing the Ghadr movement in Punjab and the Anushilan Samiti in Bengal. However its widespread and indiscriminate use in stifling genuine political discourse made it deeply unpopular, and became increasingly reviled within India. The extension of the law in the form of the Rowlatt Act after the end of World War I was opposed unanimously by the non-official Indian members of the Viceroy's council. It became a flashpoint of political discontent and nationalist agitation, culminating in the Rowlatt Satyagraha. The act was re-enacted during World War II as Defence of India act 1939. Independent India retained the law in a number of amended forms, which have seen use in proclaimed states of national emergency including Sino-Indian War, Bangladesh crisis, The Emergency of 1975 and subsequently the Punjab insurgency.

Jugantar Patrika was a Bengali revolutionary newspaper founded in 1906 in Calcutta by Barindra Kumar Ghosh, Abhinash Bhattacharya and Bhupendranath Dutt. A political weekly, it was founded in March 1906 and served as the propaganda organ for the nascent revolutionary organisation Anushilan Samiti that was taking shape in Bengal at the time. The journal derived its name 'Jugantar' from a political novel of the same name by Bengali author Shivnath Shastri. The journal went on to lend its name to the Western Bengal wing of the Anushilan Samiti, which came to be known as the Jugantar group. The journal expounded and justified revolutionary violence against the British Raj as a political tool for independence, and denounced the right and legitimacy of the British rule in India. It was also critical of the Indian National Congress and its moderate methods which was viewed as aiding the Raj. Its target audience was the young, literate and politically motivated youth of Bengal, and was priced at one paisa.

The Dramatic Performances Act was implemented by the British Government in India in the year 1876 to police seditious Indian theatre. India, being a colony of the British Empire had begun using the theatre as a tool of protest against the oppressive nature of the colonial rule. In order to check these revolutionary impulses, the British Government proceeded to impose the Dramatic Performances Act. Following India's independence in 1947, the Act has not been repealed, and most states have introduced their own modified versions with certain amendments which have in fact, often strengthened the control of the administration over the theatre.

The Serampore Mission Press was a book and newspaper publisher that operated in Serampore, Danish India, from 1800 to 1837.

In the last quarter of the 18th century, Calcutta grew into the first major centre of commercial and government printing. For the first time in the context of South Asia it becomes possible to talk of a nascent book trade which was full-fledged and included the operations of printers, binders, subscription publishing and libraries.

Sudhamoy Pramanick was a Bengali advocate from Shantipur. He was the lifetime secretary of the Tili Samaj, a societal benefit organization. In his time he was one of the fortunate Presidencians - a year senior to Rajendra Prasad, the first President of India. He was a social activist - member of the executive committee of the Indian National Congress and involved with the Satyagraha movement to campaign for Indian independence.

Sisir Kumar Ghosh (1840–1911), also spelt Shishir Kumar Ghose, was an Indian journalist, founder of the Amrita Bazar Patrika, a Bengali language newspaper, in 1868, and an independence activist from Bengal.

Krishna Patrika is an Indian Telugu-language newspaper. It was founded in 1902 by Konda Venkatappayya and Dasu Narayana Rao as a weekly magazine. Mutnuri Krishna Rao was the editor of the publication from 1907 until his death in 1945.

The Bengal famine of 1943-44 was a major famine in the Bengal province in British India during World War II. An estimated 2.1 million, out of a population of 60.3 million, died from starvation, malaria and other diseases aggravated by malnutrition, population displacement, unsanitary conditions, and lack of health care. Millions were impoverished as the crisis overwhelmed large segments of the economy and social fabric.

Freedom of the press in British India or freedom of the press in pre-independence India refers to the censorship on print media during the period of British rule by the British Crown on the Indian subcontinent from 1858 to 1947. The British Indian press was legally protected by the set of laws such as Vernacular Press Act, Censorship of Press Act, 1799, Metcalfe Act and Indian Press Act, 1910, while the media outlets were regulated by the Licensing Regulations, 1823, Licensing Act, 1857 and Registration Act, 1867. The British administrators in the India subcontinent brought a set of rules and regulations into effect designed to prevent circulating claimed inaccurate, media bias and disinformation across the subcontinent.

Censorship in the Dutch East Indies was significantly stricter than in the Netherlands, as the freedom of the press guaranteed in the Constitution of the Netherlands did not apply in the country's overseas colonies. Before the twentieth century, official censorship focused mainly on Dutch-language materials, aiming at protecting the trade and business interests of the colony and the reputation of colonial officials. In the early twentieth century, with the rise of Indonesian nationalism, censorship also encompassed materials printed in local languages such as Malay and Javanese, and enacted a repressive system of arrests, surveillance and deportations to combat anti-colonial sentiment.