Alan Alexander Milne was an English writer best known for his books about the teddy bear Winnie-the-Pooh, as well as for children's poetry. Milne was primarily a playwright before the huge success of Winnie-the-Pooh overshadowed all his previous work. Milne served in both World Wars, as a lieutenant in the Royal Warwickshire Regiment in the First World War and as a captain in the Home Guard in the Second World War.

Tigger is a fictional character, an anthropomorphic stuffed tiger. He was originally introduced in the 1928 story collection The House at Pooh Corner, the sequel to the 1926 book Winnie-the-Pooh by A. A. Milne. Like other Pooh characters, Tigger is based on one of Christopher Robin Milne's stuffed toy animals. He appears in the Disney animated versions of Winnie the Pooh and has also appeared in his own film, The Tigger Movie (2000).

Christopher Robin is a character created by A. A. Milne, based on his son Christopher Robin Milne. The character appears in the author's popular books of poetry and Winnie-the-Pooh stories, and has subsequently appeared in various Disney adaptations of the Pooh stories.

Eeyore is a fictional character in the Winnie-the-Pooh books by A. A. Milne. He is generally characterized as a pessimistic, gloomy, depressed, anhedonic, old grey stuffed donkey who is a friend of the title character, Winnie-the-Pooh.

A Heffalump is a type of elephant-like character in the Winnie-the-Pooh stories by A. A. Milne. Heffalumps are mentioned, and only appear, in Pooh and Piglet's dreams in Winnie-the-Pooh (1926), and seen again in The House at Pooh Corner (1928). Physically, they resemble elephants; E. H. Shepard's illustration shows an Indian elephant. They are later featured in the animated television series The New Adventures of Winnie the Pooh (1988–1991), followed by two animated films in 2005, Pooh's Heffalump Movie and Pooh's Heffalump Halloween Movie.

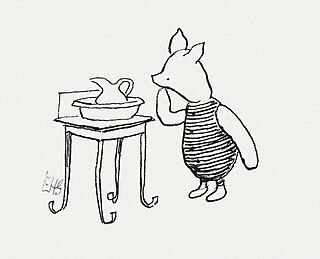

Piglet is a fictional character from A. A. Milne's Winnie-the-Pooh books. Piglet is Winnie‑the‑Pooh's closest friend amongst all the toys and animals featured in the stories. Although he is a "Very Small Animal" of a generally timid disposition, he tries to be brave and on occasion conquers his fears.

Roo is a fictional character created in 1926 by A. A. Milne and first featured in the book Winnie-the-Pooh. He is a young kangaroo and his mother is Kanga. Like most other Pooh characters, Roo is based on a stuffed toy animal that belonged to Milne's son, Christopher Robin Milne. Though stuffed, Roo was lost in the 1930s in an apple orchard somewhere in Sussex.

Winnie-the-Pooh is a 1926 children's book by English author A. A. Milne and English illustrator E. H. Shepard. The book is set in the fictional Hundred Acre Wood, with a collection of short stories following the adventures of an anthropomorphic teddy bear, Winnie-the-Pooh, and his friends Christopher Robin, Piglet, Eeyore, Owl, Rabbit, Kanga, and Roo. It is the first of two story collections by Milne about Winnie-the-Pooh, the second being The House at Pooh Corner (1928). Milne and Shepard collaborated previously for English humour magazine Punch, and in 1924 created When We Were Very Young, a poetry collection. Among the characters in the poetry book was a teddy bear Shepard modelled after his son's toy. Following this, Shepard encouraged Milne to write about his son Christopher Robin Milne's toys, and so they became the inspiration for the characters in Winnie-the-Pooh.

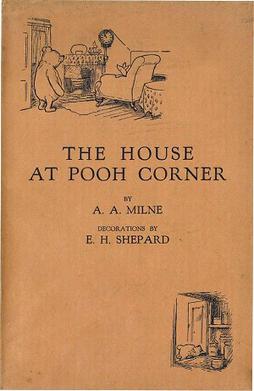

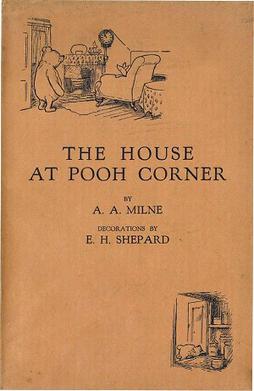

The House at Pooh Corner is a 1928 children's book by A. A. Milne and illustrated by E. H. Shepard. This book is the second novel, and final one by Milne, to feature Winnie-the-Pooh and his world. The book is also notable for introducing the character, Tigger. The book's exact date of publication is unknown beyond the year 1928, but it was likely towards the end of the year as book reviews for the book began appearing during October 1928.

Christopher Robin Milne was an English author and bookseller and the only child of author A. A. Milne. As a child, he was the basis of the character Christopher Robin in his father's Winnie-the-Pooh stories and in two books of poems.

Ann Thwaite is a British writer who is the author of five major biographies. AA Milne: His Life was the Whitbread Biography of the Year, 1990. Edmund Gosse: A Literary Landscape was described by John Carey as "magnificent - one of the finest literary biographies of our time". Glimpses of the Wonderful about the life of Edmund Gosse's father, Philip Henry Gosse, was picked out by D. J. Taylor in The Independent as one of the "Ten Best Biographies" ever. Her biography of Frances Hodgson Burnett was originally published as Waiting for the Party (1974) and reissued in 2020 with the title Beyond the Secret Garden, with a foreword by Jacqueline Wilson. Emily Tennyson, The Poet's Wife (1996) was reissued by Faber Finds for the Tennyson bicentenary in 2009.

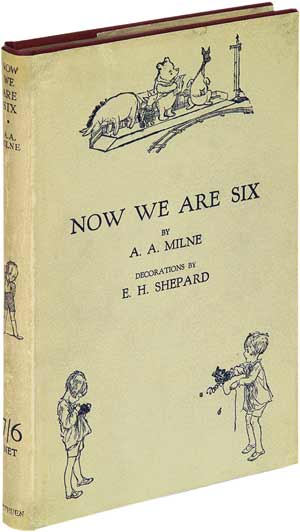

Now We Are Six is a 1927 book of children's poetry by A. A. Milne, with illustrations by E. H. Shepard. It is the second collection of children's poems following Milne's When We Were Very Young, which was first published in 1924. The collection contains thirty-five verses, including eleven poems that feature Winnie-the-Pooh illustrations.

The Book of Pooh is an American children's television series that aired on the Playhouse Disney block on Disney Channel. It is the third television series to feature the characters from the Disney franchise based on A. A. Milne's works; the other two were the live action Welcome to Pooh Corner and the animated The New Adventures of Winnie the Pooh which ran from 1988 to 1991. It premiered on January 22, 2001 and completed its run on July 8, 2003. It was repeated on Playhouse Disney until June 2, 2006. The show is produced by Shadow Projects. Walt Disney Pictures released the first of two films, a direct-to-video spin-off film based on the puppetry television series titled The Book of Pooh: Stories from the Heart in 2001.

Harold Fraser-Simson was an English composer of light music, including songs and the scores to musical comedies. His most famous musical was the World War I hit The Maid of the Mountains, and he later set numerous children's poems to music, especially those of A. A. Milne.

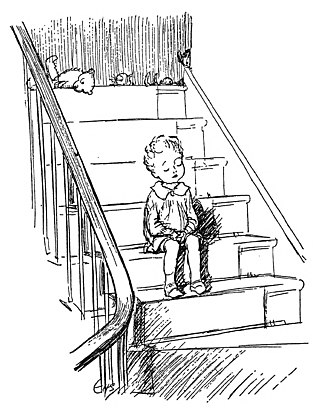

"Halfway Down" is a poem by A.A. Milne, included in the 1924 collection When We Were Very Young. A "juvenile meditation", Zena Sutherland comments in Children & Books that both the poem and Ernest Shepard's illustration "has caught the mood of suspended action that is always overtaking small children on stairs." Christopher Robin, the child in Milne's Winnie the Pooh stories, is the presumed narrator of the poem.

When We Were Very Young is a best-selling book of poetry by A. A. Milne. It was first published in 1924, and it was illustrated by E. H. Shepard. Several of the verses were set to music by Harold Fraser-Simson. The book begins with an introduction entitled "Just Before We Begin", which, in part, tells readers to imagine for themselves who the narrator is, and that it might be Christopher Robin. The 38th poem in the book, "Teddy Bear", that originally appeared in Punch magazine in February 1924, was the first appearance of the famous character Winnie-the-Pooh, first named "Mr. Edward Bear" by Christopher Robin Milne. In one of the illustrations of "Teddy Bear", Winnie-the-Pooh is shown wearing a shirt which was later coloured red when reproduced on a recording produced by Stephen Slesinger. This has become his standard appearance in the Disney adaptations. On 1 January 2020, When We Were Very Young entered the public domain in the United States, but remains protected in other countries, including the UK.

Winnie-the-Pooh is a fictional anthropomorphic teddy bear created by English author A. A. Milne and English illustrator E. H. Shepard. Winnie-the-Pooh first appeared by name in a children's story commissioned by London's Evening News for Christmas Eve 1925. The character is based on a stuffed toy that Milne had bought for his son Christopher Robin in Harrods department store.

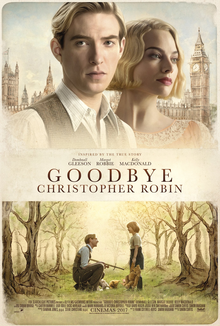

Goodbye Christopher Robin is a 2017 British biographical drama film about the lives of Winnie-the-Pooh creator A. A. Milne and his family, especially his son Christopher Robin. It was directed by Simon Curtis and written by Frank Cottrell-Boyce and Simon Vaughan, and stars Domhnall Gleeson, Margot Robbie, and Kelly Macdonald. The film premiered in the United Kingdom on 29 September 2017. It received mixed reviews from critics and grossed $7.2 million at the box office.

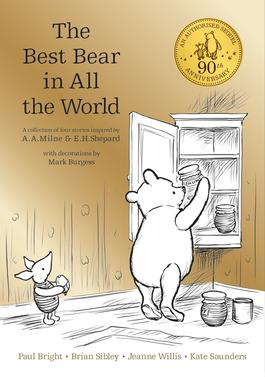

Winnie-the-Pooh: The Best Bear in All the World is the second authorised sequel to A. A. Milne's original Winnie-the-Pooh stories. It was published on 6 October 2016 to mark the 90th anniversary of the publication of the first Winnie-the-Pooh book. The sequel is an anthology of four short stories, each written by a leading children's author. The four contributors are Paul Bright, Jeanne Willis, Kate Saunders, and Brian Sibley. The illustrations, in the style of the originals by E. H. Shepard, are by Mark Burgess. The book attracted national press coverage because of the introduction of a new character, Penguin.