A letter is a written message conveyed from one person to another through a medium. Something epistolary means that it is a form of letter writing. The term usually excludes written material intended to be read in its original form by large numbers of people, such as newspapers and placards, although even these may include material in the form of an "open letter". The typical form of a letter for many centuries, and the archetypal concept even today, is a sheet of paper that is sent to a correspondent through a postal system. A letter can be formal or informal, depending on its audience and purpose. Besides being a means of communication and a store of information, letter writing has played a role in the reproduction of writing as an art throughout history. Letters have been sent since antiquity and are mentioned in the Iliad. Historians Herodotus and Thucydides mention and use letters in their writings.

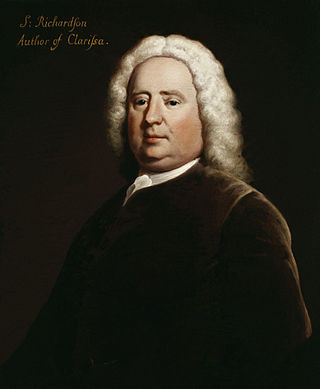

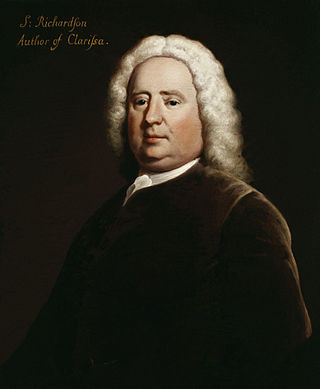

Samuel Richardson was an English writer and printer known for three epistolary novels: Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded (1740), Clarissa: Or the History of a Young Lady (1748) and The History of Sir Charles Grandison (1753). He printed almost 500 works, including journals and magazines, working periodically with the London bookseller Andrew Millar. Richardson had been apprenticed to a printer, whose daughter he eventually married. He lost her along with their six children, but remarried and had six more children, of whom four daughters reached adulthood, leaving no male heirs to continue the print shop. As it ran down, he wrote his first novel at the age of 51 and joined the admired writers of his day. Leading acquaintances included Samuel Johnson and Sarah Fielding, the physician and Behmenist George Cheyne, and the theologian and writer William Law, whose books he printed. At Law's request, Richardson printed some poems by John Byrom. In literature, he rivalled Henry Fielding; the two responded to each other's literary styles.

Emily Elizabeth Dickinson was an American poet. Little-known during her life, she has since been regarded as one of the most important figures in American poetry. Dickinson was born in Amherst, Massachusetts, into a prominent family with strong ties to its community. After studying at the Amherst Academy for seven years in her youth, she briefly attended the Mount Holyoke Female Seminary before returning to her family's home in Amherst. Evidence suggests that Dickinson lived much of her life in isolation. Considered an eccentric by locals, she developed a penchant for white clothing and was known for her reluctance to greet guests or, later in life, even to leave her bedroom. Dickinson never married, and most of her friendships were based entirely upon correspondence.

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu was an English aristocrat, writer, and poet. Born in 1689, Lady Mary spent her early life in England. In 1712, Lady Mary married Edward Wortley Montagu, who later served as the British ambassador to the Sublime Porte. Lady Mary joined her husband on the Ottoman excursion, where she was to spend the next two years of her life. During her time there, Lady Mary wrote extensively on her experience as a woman in Ottoman Constantinople. After her return to England, Lady Mary devoted her attention to the upbringing of her family before dying of cancer in 1762.

The "Dear Boss" letter was a message allegedly written by the notorious unidentified Victorian serial killer known as Jack the Ripper. Addressed to the Central News Agency of London and dated 25 September 1888, the letter was postmarked and received by the Central News Agency on 27 September. The letter itself was forwarded to Scotland Yard on 29 September.

A love letter is an expression of love in written form. However delivered, the letter may be anything from a short and simple message of love to a lengthy explanation and description of feelings.

Laura Cereta was one of the most notable humanist and feminist writers of fifteenth-century Italy. Cereta was the first to put women’s issues and her friendships with women front and center in her work. Cereta wrote in Brescia, Verona, and Venice in 1488–92, known for her writing in the form of letters to other intellectuals. Her letters contained her personal matters and childhood memories, and discussed themes such as women’s education, war, and marriage. Like the first great humanist Petrarch, Cereta claimed to seek fame and immortality through her writing. It appeared that her letters were intended for a general audience.

A valediction, or complimentary close in American English, is an expression used to say farewell, especially a word or phrase used to end a letter or message, or a speech made at a farewell.

Jane Baillie Carlyle was a Scottish writer and the wife of Thomas Carlyle.

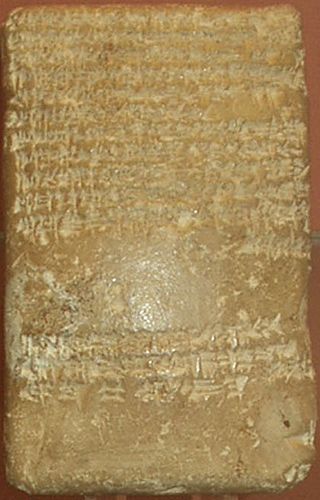

Zita was a Hittite prince and probably the brother of Suppiluliuma I,, in the 382–letter correspondence called the Amarna letters. The letters were mostly sent to the pharaoh of Egypt from 1350-1335 BC, but other internal letters, vassal-state letters, and epics, also word texts, are part of the letter corpus. Zita had a son called Hatupiyanza.

Karduniaš, also transcribed Kurduniash, Karduniash, Karaduniše, ) is a Kassite term used for the kingdom centered on Babylonia and founded by the Kassite dynasty. It is used in the 1350-1335 BC Amarna letters correspondence, and is also used frequently in Middle Assyrian and Neo-Assyrian texts to refer to the kingdom of Babylon. The name Karaduniyaš is mainly used in the letters written between Kadashman-Enlil I or Burna-Buriash, Kings of Babylon, and the Pharaoh of Ancient Egypt -, letters EA 1-EA 11, a subcorpus of letters,.

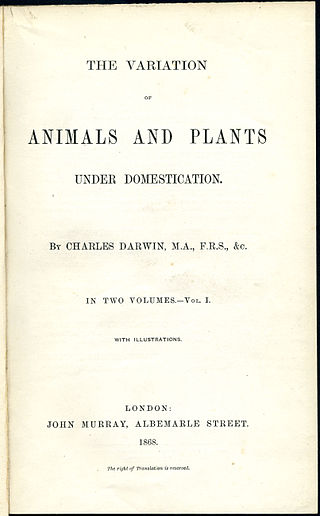

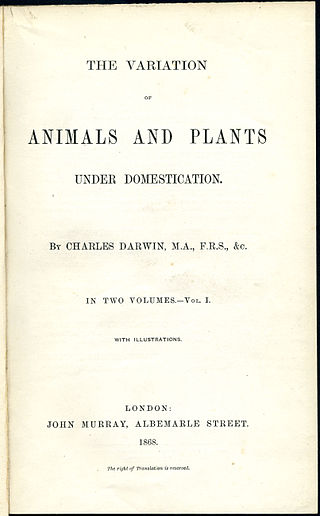

The Variation of Animals and Plants Under Domestication is a book by Charles Darwin that was first published in January 1868.

Susan Huntington Gilbert Dickinson was an American writer, poet, traveler, and editor. She was the sister-in-law of poet Emily Dickinson.

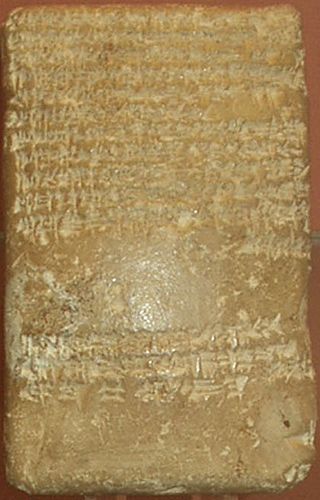

Amarna letter EA 19 is a tall clay tablet letter of 13 paragraphs, in relatively pristine condition, with some minor flaws on the clay, but a complete enough story that some included words can complete the story of the letter. Entitled "Love and Gold", the letter is about gold from Egypt, love between father-king ancestors and the current relationship between the King of Mitanni and the Pharaoh of Misri (Egypt), and marriage of women from King Tushratta of Mitanni to the Pharaoh of Egypt.

Mary Diana Dods (1790–1830) was a Scottish writer of books, stories and other works who adopted a male identity. Most of his works appeared under the pseudonym David Lyndsay. In private life he used the name Walter Sholto Douglas. This may have been partly inspired by his grandfather's name, Sholto Douglas, 15th Earl of Morton. He was a close friend and confidante of Mary Shelley, and lived a portion of his life as the husband of Isabella Robinson. In 1980, scholar Betty T. Bennett sensationally revealed that Dods performed both male identities for various literary and personal reasons.

The Amarna letter EA1 is part of an archive of clay tablets containing the diplomatic correspondence between Egypt and other Near Eastern rulers during the reign of Pharaoh Akhenaten, his predecessor Amenhotep III and his successors. These tablets were discovered in el-Amarna and are therefore known as the Amarna letters. All of the tablets are inscribed with cuneiform writing.

Amarna Letter EA3 is a letter of correspondence between Nimu'wareya, this being the ruler of Egypt, Amenḥotep III, and Kadašman-Enlil, the king of Babylon. In the Moran translation, the letter is given the cursory or synoptic title Marriage, grumblings, a palace opening. The letter is part of a series of correspondences from Babylonia to Egypt, which run from EA2 to EA4 and EA6 to EA14. EA1 and EA5 are from Egypt to Babylonia.

Amarna Letter EA4 is a continuation of correspondence between Kadašman-Enlil I and Amenhotep III.

On October 8, 1852, Maria Perkins, an enslaved woman in Charlottesville, Virginia, United States, addressed a letter to her husband, also enslaved. In the letter, she shares the news that their son Albert has been sold to a trader, expresses fears that she too might be sold, and says that she wants her family to be reunited. Perkins was literate, something uncommon among slaves, and all that is known about her comes from this letter.

Amarna letter EA 38, titled A Brotherly Quarrel, is a letter from the King of Alashiya. One identifier of many of the Amarna letters, is the use of paragraphing. Six paragraphs are in this letter, with much of the letter's reverse – uninscribed.